Chapter 2

| Jurisdiction | United States |

"Make sure that you always have the right tools for the job. It's no use trying to eat a steak with a teaspoon, and a straw."

Anthony T. Hincks, author

A. Visuals

1. Persuasion

Why is it imperative that litigators utilize visuals to persuade? At least five reasons exist. First, your audience—judge, jury, arbitrator, mediator, or your opponent—is accustomed to receiving information through visual media—Internet, videos, and broadcasts. They are attached to cell phones, laptops, and tablets. They expect to have information delivered with images. They are immersed in visual communication. Second, a major segment of the population is composed of visual learners as opposed to auditory and kinesthetic learners. Third, we retain more of the information if we receive it visually. Fourth, visual communication, such as seeing a picture of an injury, can be much more powerful than mere words describing it. Visuals can dynamically present a story and an argument. Fifth, visuals help an audience reach a consensus. For example, if a trial lawyer in an automobile tort case merely told the jury that a collision took place at an intersection, each juror will have a different mental picture of the intersection based on his or her own life experience. However, if the lawyer shows the jury a picture of the intersection in question, all of the jurors will be on the same page, seeing the same image of the intersection. Visual communication of a message is successful persuasion.

Visuals can be employed in all phases of litigation. They can be used in pretrial briefings and in alternative dispute resolution settings, as we describe in Chapter 7, or in any phase of trial from opening statement through closing argument, as we discuss in Chapters 3-6.

2. Purposes Served

Visuals can serve at least four purposes. First, narrative visuals relate the factual theory of the case; they are storytelling images. Second, argument visuals present the proponent's arguments for a favorable settlement or verdict. Third, educational visuals teach, explaining complicated information in a way that can be understood by the jurors. Fourth, concession visuals are designed to extract admissions from the opposing party or adverse witness during cross-examination or to discredit the witness who denies what is apparent in the concession visual.

a. Narrative Visuals

The popular saying is that an image is worth a thousand words. This has become a cliche because of how true it turns out to be. Images tell stories. Narrative visuals can bring the story of the case alive and make it clear for the audience. A narrative visual is ideal for opening statement, which is the golden opportunity for counsel to be a storyteller. A narrative visual helps the jury understand the facts. For example, with the aid of an anatomical drawing, plaintiff's counsel in a personal injury case can relate a human story about the plaintiff's injuries that are at the core of the case. The images of the injuries and the plaintiff's recovery from those injuries can tell a profoundly sympathetic story that motivates jurors to want to compensate the plaintiff. Furthermore, counsel can effectively communicate the events that took place with the aid of a timeline that will help the jury understand and retain the chronology of those events. Another example of a narrative visual that can help the jury understand and retain information is a relationship visual, which is a diagram with pictures of players in the case with arrows between them along with short labels showing how they are connected with one another. Finally, the defense might rely on a decision-tree graphic that shows a pattern of poor decision making by the plaintiff that led to the unfortunate outcome. We discuss many more narrative visuals in Chapter 3 on opening statements.

b. Argument Visuals

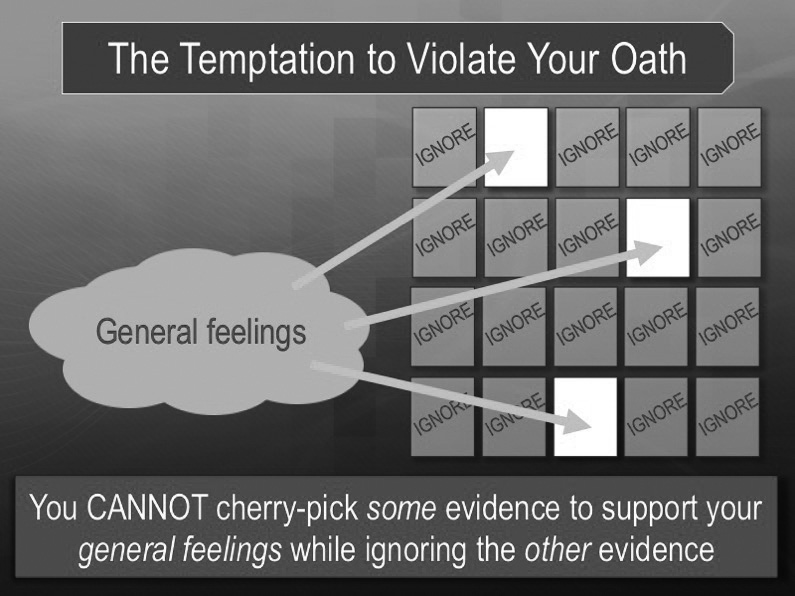

An argument visual is a visual aid that counsel can use to communicate the attorney's argument during summation. As opposed to narrative visuals that convincingly relay facts during opening statement, argument visuals explain why the jury should decide in the party's favor. Argument visuals ideally are simple, easy to understand, and persuasively communicate the lawyer's argument. There are an infinite number of argument visuals because there are a vast number of arguments that counsel can make in closing. For example, defense counsel may use the visual below to highlight jurors' temptations to overlook key hurdles for the prosecution in a criminal case or the plaintiff in a civil case.

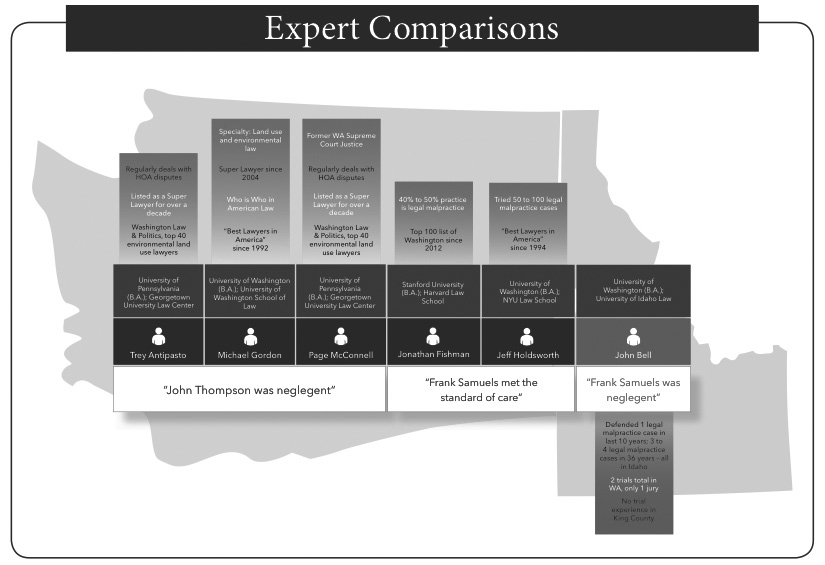

Argument visuals also can be used to undercut the other side's case. For instance, counsel can utilize a chart contrasting the superior qualifications of the party's expert with the opposing party's expert's qualifications when arguing that the jury should rely on their expert. Consider the following example that was used in a legal malpractice case.

In the foregoing example, the defense used this graphic to argue that its experts are local, reputable Washington attorneys, while the plaintiff's expert was an out-of-state Idaho attorney with limited experience and expertise. The defense experts' qualifications are described in the five boxes on the left with summaries of their qualifications. The plaintiff's expert is depicted on the right below the line with a text box that states:

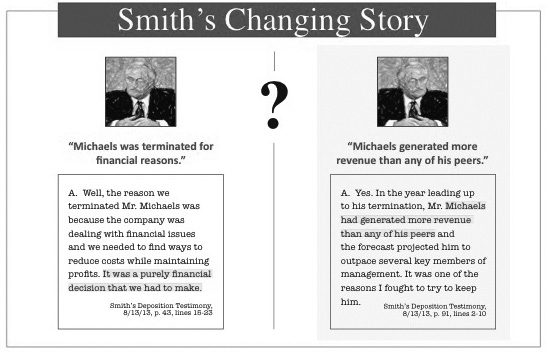

Another example of an argument visual is a chart contrasting the portions of the testimony of the other side's key witness with conflicting credible evidence, such as in the following example.

In Chapter 4 on closing arguments, we discuss several other powerful argument visuals.

c. Educational Visuals

Educational visuals can be employed to help the audience understand the evidence. When the evidence is complex, educational visuals can be particularly helpful. Evidence can be complex when it is technical, and it can also be complex when it is voluminous. Indeed, Federal Rule of Evidence 1006 codifies this principle that a visual may be useful in communicating information by authorizing the use of a summary chart "to prove the content of voluminous writings. . . ."

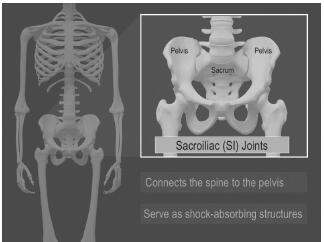

Educational visual aids are a staple for an expert witness's direct examination, enabling the expert to employ a visual to explain and simplify the complex. For example, a physician can employ a medical illustration to explain her findings and conclusions, such as in the following example where a medical expert was educating jurors about the sacroiliac joint.

Alternatively, a vehicular accident reconstructionist may use a forensic video animation of a collision,1 such as the one below, to help the jury understand the expert's findings and opinions. We provide several of the education visuals in Chapter 5 on direct examination.

d. Concession Visuals

Concession visuals are those that do one or more of the following: force a witness to make a concession favorable to a cross-examiner; impeach the witness; or highlight a key concession in closing argument. There are some things a witness either must admit or in denying them, label the answer a lie, mistaken, or ludicrous.

A concession visual can destroy a witness's credibility. A concession visual is one that reveals the irrefutable truth, which can be proven by direct or circumstantial evidence or by plain common sense. In Chapter 6 on cross-examination we provide several examples of concession visuals that impeached the witnesses who were confronted with them. An example of a concession visual is a witness's prior inconsistent statement in a video deposition. When the witness is shown the prior inconsistent statement, the witness must concede that he made the statement or stamp his denial as false.

3. Design Criteria for Demonstrative Evidence

For a piece of demonstrative evidence (hereafter also referred to as "a demonstrative") to produce a favorable impression, it must satisfy certain design criteria. The design of these demonstratives (here we are referring to graphics, such as a diagram, timeline, drawing, or animation) must be credible, interesting, and easily understood by the audience.

First, the demonstrative evidence must be credible. Edward Tufte, American renowned statistician, artist, and author, stated:

Making an evidence presentation is a moral act as well as an intellectual activity. To maintain standards of quality, relevance, and integrity for evidence, consumers of presentations should insist that presenters be held intellectually and ethically responsible for what they show and tell. Thus, consuming a presentation is also an intellectual and moral activity.2

An audience will only be swayed and/or educated by what they see as believable. Therefore, the designer of the demonstrative evidence should make sure that the visual portrays the indisputable. An image is credible when it states the law, such as an argument visual that tracks the wording of a jury instruction. A visual that shows what is irrefutable or overwhelming evidence is credible. A visual that makes common sense is believable. A visual that shows what is accepted as common knowledge is credible.

Second, to be effective the visual should be interesting. It should engage the jurors. When a visual is creative, it can be interesting. When the visual presents the unexpected, it is likely to capture the jurors' attention. This is important because keeping jurors' attention is critical at trial, though it is becoming more and more difficult. Research on social media and technology suggests that one consequence of the technology revolution is diminished attention spans. Visual communication can help overcome this hurdle by engaging jurors and capturing their attention.

Third, the demonstrative should be easily understood by the audience. In 1968, American educator Malcomb S. Knowles...

To continue reading

Request your trial