Chapter 9A THE LEGAL LANDSCAPE OF PRIVATE WATER INVESTMENTS

| Jurisdiction | United States |

[Page 9A-1]

THE LEGAL LANDSCAPE OF PRIVATE WATER INVESTMENTS

BARTON "BUZZ" THOMPSON is a global expert on water resources and focuses on how to improve resource management through legal, institutional, and technological innovation. He was the founding Perry L. McCarty Director of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, where he remains a Senior Fellow and directs the Water in the West program. He also has been a Senior Fellow (by courtesy) at Stanford's Freeman-Spogli Institute for International Studies, and a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. He founded the law school's Environmental and Natural Resources Program. Professor Thompson is of counsel to the law firm of O'Melveny & Myers, where he specializes in water resources. He was a partner at O'Melveny & Myers prior to joining Stanford Law School. He also serves as an advisor to the Sustainable Water Impact Fund, a billion-dollar impact investment fund focused on water resources. He chairs the boards of the Resources Legacy Fund and the Stanford Habitat Conservation Board, is a California trustee of The Nature Conservancy, and is a board member of the Sonoran Institute and the Santa Lucia Conservancy. He is former board chair of the American Farmland Trust. Professor Thompson served as Special Master for the United States Supreme Court in Montana v. Wyoming, an interstate water dispute involving the Yellowstone River system. He also is a former member of the Science Advisory Board of the United States Environmental Protection Agency. He was a law clerk to Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist '52 (BA '48, MA '48) of the U.S. Supreme Court and Judge Joseph T. Sneed of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

I. Water Markets & Controversies

Water markets have long been controversial, in part because of a fear of private investors and "speculation." Elwood Mead, who as Wyoming's State Engineer from 1888 and 1899 helped develop its prior appropriation system, opposed water markets for fear they would lead to private "speculation." Mead worried that, if water could be marketed, water users would appropriate more water than they needed in the speculative hope that they could later sell the excess water when local water became scarce and thus economically valuable.2

Mead's concerns extended beyond the purely practical worry that people would appropriate excess water just to sell it. Mead also feared that water markets might lead to monopolies in water. "The growth and danger of monopolies in oil, copper, coal, and iron afford a warning of the greater danger of permitting monopolies in water."

Mead also disliked the idea that appropriators might profit from water that the state provided for free. Mead believed that water was appropriately available for free appropriation because it, like air and sunshine, were "gifts from God." This view should not be "lightly set aside even in arid lands." But Mead also believed that, if "water is to be ... bartered and sold then the public should not give streams away, but should auction them off to the highest bidder." Water, in short, should remain free, and if anyone were to profit, it should be the government.

Finally, Mead felt that water marketing was inherently unjust. Water resources, Mead believed, "belong to the people, and ought forever to be kept as public property for the benefit of all who use them, and for them alone, such use to be under public supervision and control." If you were not putting water to beneficial use, Mead did not believe you should own water.

Mead's views ultimately convinced the Wyoming legislation to gut water markets. Appropriators were still able to sell their water rights in Wyoming, but those water rights lost all seniority upon transfer - making water transfers effectively the same as new appropriations and thus worthless.3 Most of the early western legislatures, like that of Wyoming, were

[Page 9A-2]

suspicious of and hostile to water markets. As a result, most western states ultimately passed laws prohibiting or severely restricting the severance of appropriative rights from the lands to which they were appurtenant. These states included, at one time or another, Arizona, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Wyoming.4

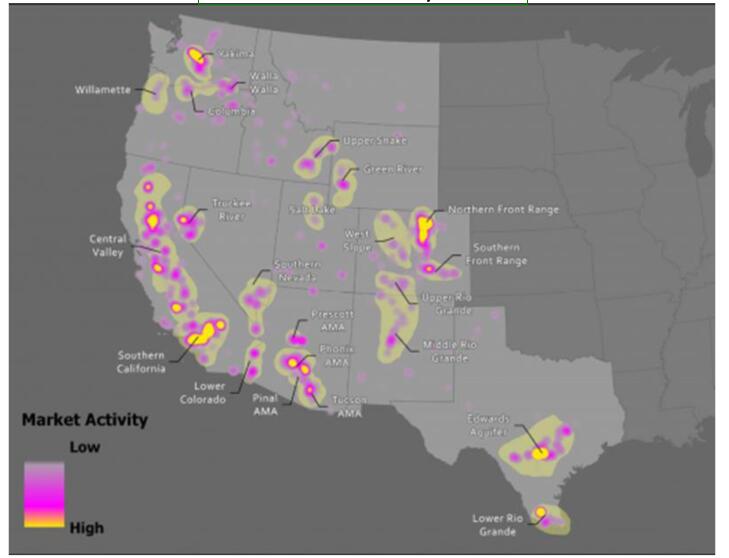

Times and attitudes have changed.5 All appropriation states today permit some form of water marketing. Water markets, moreover, have grown materially over the last forty years. California water markets handle the highest volume of water, while Colorado has the highest volume of trades. As Figure 1 illustrates, however, virtually all western states have significant water markets.

Source: WestWater Research (access on Nasdaq, https://www.nasdaq.com/solutions/nasdaq-veles-water-index)

[Page 9A-3]

Water trades in the United States occur in a variety of settings and can take place in various ways. Principal categories of water trades include:

• Formal Trading of Appropriative Water Rights: When most people think of water markets, they think of the sale or temporary transfer of appropriative water rights by one user to another. State regulatory agencies must generally approve these transactions and ensure that the transfer does not injure other appropriators.6

• Groundwater Markets: Limits on groundwater withdrawals, through either regulation or adjudications, frequently lead to the creation of local groundwater markets to help ensure that the limited groundwater is used efficiently and thereby minimize local economic impacts. In most cases, groundwater trades do not need state approval, although they are generally regulated by a local groundwater agency or watermaster.7

• Water Banks: States and regional water agencies have sometimes encouraged the transfer of water rights through the establishment of formal "water banks" in which the bank buys and sells rights under specific rules and often at a pre-set price. These transfers again generally do not require state approval.8

• Intra-Institutional Markets: Water districts and mutual water companies often have robust internal water markets in which their members trade their water entitlements. Such internal transfers generally do not need formal state approval unless a member wishes to use water outside the institution's geographic boundaries.9

• Governmental Water Sales/Leases: In some cases, water agencies offer water for sale to end users through long-term contracts or leases. Examples in Colorado include the Colorado River District Water Market and the City of Boulder's water leasing program.10

• Forbearance Agreement: If a downstream user needs additional water, upstream users can sometimes enter into forbearance agreements in which they agree not to divert their water. Forbearance agreements do not need to go through formal state approval, but they have limited usefulness because of both forfeiture/abandonment policies (that limit the possible period of forbearance) and prior appropriative rules (that can sometimes entitle other appropriators to divert the water that is not being used).11

[Page 9A-4]

While water markets have grown over the last forty years, they continue to be controversial. Many of the concerns have nothing to do with concerns about private investors. These include:

• Community Impacts: Where water is transferred out of a region, the local community sometimes worries that the transfer will reduce local economic activity and employment (along with local tax receipts and attendant governmental services). As a result, some states require that applicants for a water transfer demonstrate that the transfer will not harm the local community.12 Other states restrict transfers out of a region or impose a tax on such transfers that can fund mitigation.13

• Environmental Impacts: Another concern sometimes is that transfers may cause environmental harm. As a result, a few states also require that transfer applicants establish that the transfer will not negatively impact the environment.14

• Loss of Water to Agriculture and the Environment: Some market critics have also suggested that water markets will lead water to flow to wealthy urban communities at the expense of agricultural users (and thus food production) and/or the environment. Figure 2 shows the sources of both supply and demand for water transfers in the western United States over the last decade. Agriculture is indeed the major source of water for transfers. But environmental buyers are prominent and growing. And farmers themselves have been making increased use of water markets to ensure that they have the water they need to support their crops, particularly during droughts or in the face of climate change. Indeed, during recent California droughts, agricultural purchasers have often outbid urban buyers. Water markets, in short, do not just benefit cities but can also benefit agriculture and the environment.

| Supply | Demand |

| 1. Agriculture: 67% | 1. Municipalities: 44% |

| 2. Municipalities: 16% | 2. Environmental Buyers: 26% |

| 3. Industrial Rights: 8% | 3. Agriculture: 15% |

| 4. Investor-owned Rights: 4% | |

| Source: WestWater Research (data over last ten years on transactions across the western US) (access on Nasdaq, https://www.nasdaq.com/solutions/nasdaq-veles-water-index) |

[Page 9A-5]

• Commodification: To some observers, water markets are simply inconsistent with the public nature of water. In their view, water should not be "commodified." Government, not markets, should determine who receives water and how much each user can consume based on societal priorities rather than price.15

II. The Traditional "Anti-Speculation Doctrine"

Another frequently expressed concern about water markets - from Elwood Mead to critics today - is that "speculators" will come to dominate and...

To continue reading

Request your trial