Chapter 13 "TAKING" STOCK OF FLOOD CLAIMS

| Jurisdiction | United States |

[Page 13-1]

"TAKING" STOCK OF FLOOD CLAIMS

Local, state, and federal governments spend an incredible amount of time, effort, and tax dollars attempting to reduce the risk of flooding on private properties. These efforts are wildly successful, but rarely perfectly so. Some properties experience devastating floods despite government efforts. Other properties experience some flood damage, but far less than they would have without government interventions. Some property owners believe their property flooded only because the government acted, which perhaps protected other properties at their expense.

When floods do occur, governments spend millions, and often billions, of tax dollars in flood relief efforts. After Hurricane Sandy slammed the eastern seaboard in 2012, for example, Congress appropriated approximately $60 billion in disaster relief.2 And when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, the federal government spent more than $100 billion in recovery efforts.3 In addition to flood relief efforts, the federal government has, since 1968, spent a huge amount of federal dollars to fund the National Flood Insurance Program, which significantly subsidizes federally-backed flood insurance purchased by millions of Americans.4

Yet individuals whose properties were damaged or destroyed by flooding may feel unsatisfied with these efforts and consider their options for legal redress. Due to limitations on

[Page 13-2]

flood-based tort claims,5 many potential litigants will question whether they have a valid claim for compensation under the Fifth Amendment. Any readers who own property at risk of flooding or worry how their tax dollars are spent should care greatly about how courts resolve that question.

Due to the large number of flood-based takings claims and the significant amount of money at stake, some of the most important Fifth Amendment cases stem from floods. The courts' evaluations of these claims have evolved significantly over time, tracking and sometimes leading reinterpretations of the Takings Clause writ large. For several decades after passage of the Fifth Amendment, the United States Supreme Court understood the Takings Clause to have a limited scope, requiring the government to pay compensation only when it permanently and physically invaded real property. From that humble beginning, the Takings Clause has expanded greatly and is now understood to apply in countless other situations.

In 1922, for example, the Supreme Court confirmed that government regulatory action, without any physical invasion, might violate the Takings Clause if the "regulation goes too far. . . ."6 Decades later, the Supreme Court provided some guidance to lower courts by endorsing a multi-factor test (the so-called "Penn Central test") to assess the merits of regulatory takings claims.7 In 1987, the Supreme Court held the government might violate the Fifth Amendment by regulating property even temporarily.8 In recent years, the Supreme Court has issued important decisions in dozens of Fifth Amendment cases, addressing claim accrual,9 ripeness,10 liability11 and other issues.12

Flood-based takings claims have played an important role in this evolution of the Fifth Amendment. In 1871, for example, when the Takings Clause was given a narrow interpretation, it was understood that the government must compensate individuals for causing permanent flooding on private properties only if a "continuous[] . . . overflow . . . worked an almost complete destruction of the value of the land."13 By 2012, however, the Supreme Court concluded that the government might violate the Fifth Amendment if it caused temporarily-recurring flooding, depending on an assessment of a multi-factor liability test akin to the Penn Central test.14 In the

[Page 13-3]

years after 2012, courts have found the United States not liable for one-time flooding on thousands of properties in New Orleans coincident with Hurricane Katrina,15 but liable for one-time flooding on properties in Houston coincident with Tropical Storm Harvey.16 The Supreme Court's most recent Fifth Amendment case was far removed from a flooding disaster--it addressed whether a state statute allowing union organizers to temporarily meet on agribusinesses' properties violated the Takings Clause--but the Supreme Court nevertheless discussed how its ruling related to flood- based takings claims.17

The case law governing Fifth Amendment cases is in a state of perpetual change and uncertainty. That is understandable--this is a Constitutional issue after all. But the uncertainty is particularly acute with respect to flood-based takings claims due to the unique nature of flood disasters. As discussed in Section I, floods are the most common and the most expensive natural disaster in the United States. As our climate continues to undergo long-term changes and flooding occurs more often and with higher financial impacts, this uncertainty in the case law becomes more obvious.

This paper then focuses on two major issues that often arise in flood-based Fifth Amendment claims. Section II describes the issue of actual causation, a subject that has received significant attention in recent cases. Those cases direct courts to undertake a but-for causation analysis--to compare what actually happened on a litigant's property with what would have happened without the government action. Upcoming cases will address how to resolve that issue in more complicated fact patterns.

Section III addresses how courts assess liability in flood-based Fifth Amendment cases.18 This subject has received increased attention in recent years as courts have struggled to distinguish between cases where a per se test applies and cases where a multi-factor test applies. Upcoming cases are likely to explore how to distinguish those two categories and will likely resolve the important question of how to assess liability based on a single incident of flooding.

[Page 13-4]

I. Why Flood-Based Takings Claims Matter

Floods are the most common and the most expensive natural disaster in the United States.19 Ninety-eight percent of American counties have experienced at least one major flood event, and individual decisions about where to live exacerbate the problem flood events pose.20 As of 2020, for example, approximately 39 percent of Americans live in coastal areas, which greatly increases the possibility of experiencing flood-related losses.21

Floods have always been part of the American landscape, but the number of major floods and the associated costs have increased substantially in recent years. As a result, one must approach statistical data carefully. For example, one study published by the Pew Charitable Trust estimated that flooding caused an average of more than $7.6 billion in damage per year between 1980 and 2013.22 But flood-related costs have jumped significantly in recent years--from an average of approximately $4 billion per year in the 1980s to approximately $17 billion per year between 2010 and 2018.23

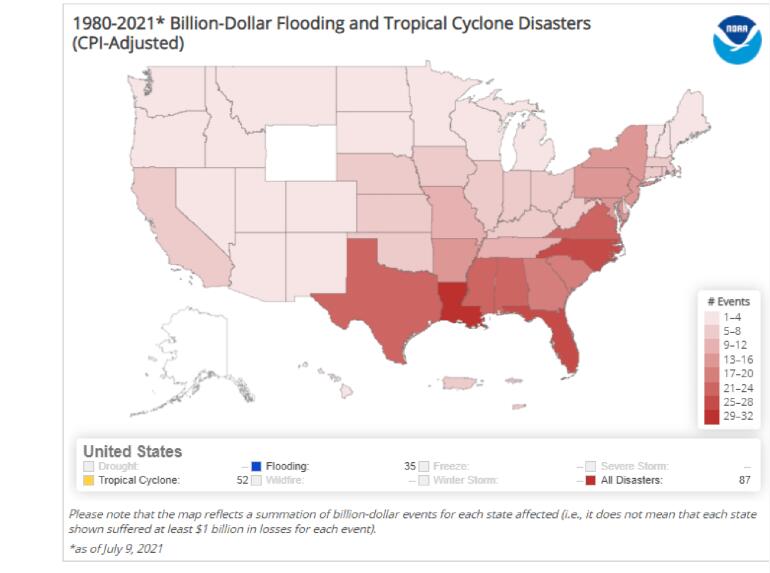

Flood events are uniquely damaging as compared to other major natural disasters. Between 1980 and 2021, for example, the United States experienced 298 weather and climate disasters-- defined as droughts, floodings, freezes, severe storms, tropical cyclones, wildfires, and winter storms--that caused damage of at least $1 billion each (adjusted to 2021 dollars).24 Thirty five of these were "Flooding Events"--meaning river basin or urban flooding resulting from excessive rainfall--and an additional 52 were "Tropical Cyclones," which are almost always accompanied by significant flooding.25 These flood-related events comprise less than 30 percent of all billion- dollar events, but caused more than 60 percent (nearly $1.2 trillion) of the total monetary damage.26 In addition, these flood-related events caused 7,217 deaths, nearly one-half of all deaths occurring

[Page 13-5]

during the 298 events.27 As the map below shows, billion-dollar flood events occur in nearly every U.S. state:

The federal government accepted the fact that flooding is a national concern following a massive 1927 flood that devastated thousands of properties in the mid-west. Extraordinary rainfall in 1926 and 1927 caused historically high stages on the Mississippi River and its tributaries, causing numerous levee breaches that would eventually inundate approximately 26,000 square miles in seven different states.28 That flood forced approximately 700,000 people to seek emergency shelter and destroyed hundreds of cities, towns and villages.29 It is estimated that direct property damages exceeded $200 million (approximately $3 billion in 2020 dollars) and some historians estimate direct and indirect damages together reached five times that amount.30 After the storm, Congress adopted the 1928 Flood Control Act, which included a plan to build the largest public works project ever authorized by the federal government, the Mississippi River and

[Page 13-6]

Tributaries Project.31 That project intends to reduce flood risks on the Mississippi River and, in the years since, Congress has authorized billions of dollars to fund other flood risk reduction projects across the United States.32

Today, the United States Army Corps of Engineers ("Corps") oversees most of the federal government's efforts to reduce flood risks on private properties. This includes continued construction and operation of the massive Mississippi River and Tributaries Project as well as numerous other projects across the country. The Corps' efforts include the building and maintenance of more than 700 dams and reservoirs, approximately 150 major coastal storm risk management systems, 11,750 miles of federally authorized levees and floodwalls, and hundreds of other projects.33

Other federal agencies and state and local entities build and manage additional flood-risk management projects across the country. When storms overcome these...

To continue reading

Request your trial