A Felicitous Meme: the Eleventh Circuit Solves the Preiser Puzzle?

| Publication year | 2022 |

A Felicitous Meme: The Eleventh Circuit Solves the Preiser Puzzle?

Lisa N. Beckmann

Arthur O. Brown

[Page 763]

This Article is about a legal phenomenon known as the Preiser Puzzle. More precisely, the article concerns a possible solution to the Preiser Puzzle articulated by the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. In part, this Article has a descriptive aim: The Authors will explain the Eleventh Circuit's solution both in the abstract (this section, below), and by giving issue—specific examples in section three that may prove useful to practitioners. Important issues at present include: (a) challenges to parole procedures, (b) method of execution challenges, and (c) requests for release from administrative segregation. Yet this Article also has an important normative aim.

To appreciate both aims, one must first revisit the Preiser Puzzle,1 and the eponymous case of Preiser v. Rodriguez.2 Preiser concerned a prisoner's claim for the restoration of good-time credits, withdrawn for bad behavior, that would have led to a speedier release.3 The prisoner advanced this claim in an action under 42 U.S.C. § 1983,4 but the Supreme Court of the United States held that the prisoner should instead have raised the claim in a habeas action.5 The Court stated that

[Page 764]

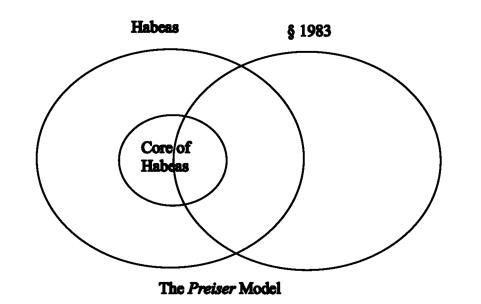

claims "attacking the very duration of . . . physical confinement" fall within the "core of habeas."6 Preiser thus stands for the proposition that core habeas claims must be raised in a habeas action, not a § 1983 action.7

Where there is a core, there is an implied penumbra, so Preiser left open the possibility of residual overlap between habeas and § 1983, which is to say that Preiser created a puzzle. In truth, though, the puzzle arises from broad statutory language. Section 1983 grants, on the one hand, a cause of action for the "deprivation of any rights . . . secured by the Constitution."8 The prisoner in Preiser, for example, asserted a due process violation based on the deprivation of good-conduct-time credits without notice of the underlying grounds, or an opportunity to challenge those grounds.9

Habeas, on the other hand, affords a remedial avenue for persons "in custody in violation of the Constitution."10 Again, Preiser explains that core habeas claims seek a shorter duration of custody.11 Suppose, though, that a prisoner argues his circumstances of confinement are inhumanly "cruel" in Eighth Amendment jargon. This claim, if valid, could be remedied through an outright release obtained in a habeas action, but the cruel nature of the prisoner's confinement might alternatively be remedied through corrective changes to the custodial facility, or by a transfer to a less cruel facility. Conceivably, these latter remedies could be obtained in either a habeas action or in a § 1983 action, although prevailing thought prefers the § 1983 route. The crucial point is that by carving out a core of habeas, Preiser acknowledged an overlap between § 1983 and penumbral habeas issues, and it left to lower courts the delicate task of navigating this overlap.12

[Page 765]

The residual overlap between habeas and § 1983 is undesirable for two reasons. One reason is the goal of judicial efficiency in face of steadily numerous prisoner filings. During the twelve-month period ending on March 31, 2020, for example, state prisoners commenced in the federal district courts approximately 42,400 habeas and § 1983 actions combined.13 The Preiser Puzzle impedes the courts' ability to efficiently process these cases.

A second reason is fairness to litigants, who must untangle the Preiser Puzzle in an effort merely to present their claims for a hearing on the merits. Courts and scholars have, for decades now, expressed frustration over Preiser's lack of guidance and workability.14 If trained jurists cannot solve the Preiser Puzzle, then it is unreasonable to expect pro se prisoners to do so.15

[Page 766]

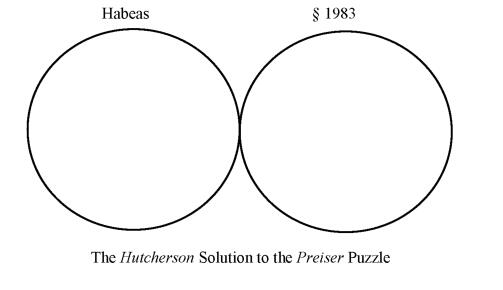

It is in this context that one should adjudge a possible solution to the Preiser Puzzle articulated by the Eleventh Circuit. Beginning with Hutcherson v. Riley,16 the Eleventh Circuit declared that habeas and § 1983 offer "mutually exclusive" avenues for relief.17 This possible answer to Preiser, what this Article dubs the Hutcherson approach, obviates the need for any notion of a core of habeas.18 Rather, the Hutcherson approach elides core and penumbral habeas issues, thereby creating a seemingly simple binary choice that is the product of a bright-line rule. Under Hutcherson, courts simply ask whether a claim should be raised in habeas or § 1983.19

Bright line rules promote clarity, and for that reason, it is the Authors' opinion that the Hutcherson approach is, on balance, desirable. That normative conclusion, though, is a close call because the Eleventh Circuit's rule of mutual exclusivity is dubious for many reasons. Section four of this Article discusses practical problems, such as the burden of determining, through a trial-and-error process, what claims correspond to which action type, either habeas or § 1983. Section four also addresses the critical problem of application errors. That problem is critical because it threatens to erode Hutcherson's primary selling point, clarity.

[Page 767]

Although the bulk of this Article will focus on practical points—section three addresses mechanics, section four addresses practical problems, and section five offers a final assessment—the following section attempts to refute certain abstract criticisms that the Hutcherson approach will undoubtedly face. Chief among those criticisms is the solution's discreditable origin. In brief, the Eleventh Circuit's rule of mutual exclusivity arises from (1) a stray misstatement of Preiser's holding, and (2) a subsequent enforcement of that misstatement as a rule of law. As explained below, the Hutcherson approach appears to be a successful legal meme.

The Authors hope to give in this Article a clear-eyed assessment of the Hutcherson approach, and to explain why, despite its dubious origin and some significant drawbacks, the Hutcherson approach offers an attractive solution to the Preiser Puzzle. If the Eleventh Circuits rule of mutual exclusivity is indeed a meme, it is nevertheless a felicitous one worthy of close consideration and potential adoption by other circuits.

Before diving into the practicalities of the Hutcherson approach—namely, the questions of how and whether Hutcherson will work—the Authors hope to refute three abstract criticisms that Hutcherson is likely to face. Those criticisms, addressed in turn below, are (1) the metaphysical erosion of habeas, (2) the Eleventh Circuit's failure to provide analysis, and (3) the accusation that Hutcherson is a legal meme. None of these criticisms should forestall an adoption of Hutcherson's rule of mutual exclusivity.

A. The Metaphysical Erosion of Habeas

The mutually exclusive treatment of habeas and § 1983 is bound to require judicial line drawing, and critics will argue that some such lines erode the right to habeas corpus, as enshrined by reference in Article I, section 9, clause 2 of the United States Constitution.20 That is, when judges employing the Hutcherson approach declare that a penumbral habeas issue should be raised in a § 1983 claim, as opposed to a habeas action, critics will argue that these judges are eroding the constitutional right to habeas. That criticism is premised on the unlikely, but theoretically possible premise that Congress might repeal or significantly modify § 1983. According to critics, a penumbral habeas

[Page 768]

claim channeled into § 1983 litigation may "go poof" if § 1983 is repealed.

For reasons discussed below, the Authors believe that this criticism of Hutcherson approach is too metaphysical to take very seriously. The criticism needs mention, though, if only because members of the federal judiciary have already voiced it. Judge Berzon's dissent in Nettles v. Grounds,21 a United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit decision, offers the clearest example yet:

More broadly, the PLRA's restrictions on prisoner suits demonstrate the hazards of limiting habeas corpus due to potential overlap with other remedies. The writ of habeas corpus is protected by the Constitution. See U.S. Const. art. I, § 9, cl. 2. There is no such explicit protection for the remedy afforded by § 1983 (which, indeed, did not even exist until after the Civil War). As the PLRA shows, Congress can alter § 1983 at will, to make it more or less available to particular groups like prisoners. Relying on the existence of alternative statutory remedies to justify narrowing the breadth of habeas thus may create gaps that widen over time as Congress alters those remedies. This potential problem is made more likely if we read the existence vel non of other statutory schemes to indicate Congress's implicit intent to limit habeas's scope. Such an arrangement risks encroachment on the "grand purpose" of one of the most important remedies of our legal order.22

Of course, the criticism's appearance in a dissent suggests that it has not been overly persuasive. Yet the conventional judicial response to the criticism is not altogether convincing either because it depends upon a divining of Congressional intent. That is, the conventional judicial response, as advanced by the Nettles majority opinion, cites a supposed Congressional intent, divined from the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA)23 and the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA),24 to "channel prisoner litigation," and specifically to make § 1983 "the exclusive vehicle for suits about prison life," and "the exclusive vehicle for claims that are not within the core of habeas."25 In full, the most relevant part of the Nettles majority opinion reads as...

To continue reading

Request your trial