Chapter §9.08 Nonobviousness in the Twenty-First Century: KSR v. Teleflex (U.S. 2007)

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§9.08 Nonobviousness in the Twenty-First Century: KSR v. Teleflex (U.S. 2007)

[A] Expanding the Reasons for Combining Prior Art Teachings

The U.S. Supreme Court in 2007 issued its most important decision interpreting the nonobviousness requirement of 35 U.S.C. §103 in the 40 years that followed the Court's foundational decision in Graham v. John Deere Co.580 In KSR Int'l Co. v. Teleflex, Inc.,581 the Court significantly expanded the potential bases for combining prior art teachings to support a determination of obviousness. "Clarif[ying] that courts may look to a wider diversity of sources to bridge the gap between the prior art and a conclusion of obviousness,"582 the Supreme Court in KSR reversed the Federal Circuit's holding that an electromechanical device patented by Teleflex would not have been obvious.583 The Federal Circuit had erred by applying the TSM test too narrowly and rigidly, requiring a more precise and explicit statement of a TSM than the prior art references of record provided.

The Supreme Court's KSR decision also stressed the role of "common sense" and "predictability" in determining whether a claimed invention would have been obvious, but did not define those terms or clearly explain how they inform the statutory standard of §103.584 The net effect of the Supreme Court's KSR decision appears to be that the USPTO will more routinely and easily establish a prima facie case of obviousness, shifting the burden to patent applicants to refute or rebut such prima facie cases.585

The Supreme Court's KSR decision also makes it likely that issued patents will be challenged more frequently as claiming obvious subject matter. The KSR Court questioned (without deciding the issue) the rationale for presuming an issued patent valid under 35 U.S.C. §282 when the USPTO's examination did not consider a prior art reference later asserted by an accused infringer as evidence of invalidity.586 In making obviousness easier to establish, at least prima facie, KSR is consistent with other contemporaneous Supreme Court decisions that have questioned the appropriate balance of power in the patent system. At least some Supreme Court Justices (including Justice Kennedy, author of the KSR opinion) have expressed concern that that balance has shifted too far in favor of patent owners.587

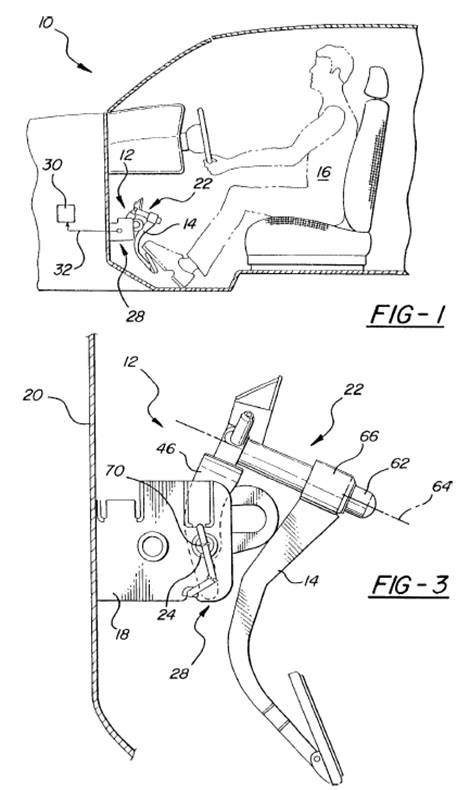

The Engelgau patent in suit in KSR, owned by Teleflex, was directed to a "vehicle control pedal apparatus" incorporating an electronic sensor in a vehicle's accelerator pedal.588 The sensor was capable of changing the pedal's position depending on the height of the vehicle's driver. More specifically, the apparatus combined the electronic sensor with an adjustable automobile pedal so that the pedal's position could be transmitted to a computer controlling the throttle in the car's engine.589 Figure 9-7 depicts two views of the Teleflex invention.

The primary prior art reference relied on by validity challenger KSR was a U.S. patent to Asano.590 The Asano patent taught an adjustable pedal in a support structure housing the pedal such that even when adjusted relative to a driver's height, one of the pedal's pivot points would remain fixed.591 The problem addressed by the Asano invention was a "constant ratio" problem—ensuring that the force required to depress the pedal always remained the same, no matter how the pedal was adjusted. Teleflex argued before the Federal Circuit that the problem its own invention solved was different—to design a smaller, less complex, and cheaper electronic pedal assembly. Teleflex contended that Asano's mechanical linkage based device was complex, expensive to make, and difficult to package.

Reversing a district court's summary judgment of invalidity under 35 U.S.C. §103, the Federal Circuit agreed with Teleflex that its invention would not have been obvious in view of the disclosures of Asano in combination with other prior art references. The appellate court emphasized that "[w]hen obviousness is based on the teachings of multiple prior art references, the movant [validity challenger] must also establish some 'suggestion, teaching, or motivation' that would have led a person of ordinary skill in the art to combine the relevant prior art teachings in the manner claimed."592 Combining references without such a TSM "simply takes the inventor's disclosure as a blueprint for piecing together the prior art to defeat patentability—the essence of hindsight."593

The Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that a TSM may be found from the nature of the problem to be solved, "leading inventors to look to references relating to possible solutions to that problem."594 However, "the test requires that the nature of the problem to be solved be such that it would have led a person of ordinary skill in the art to combine the prior art teachings in the particular manner claimed."595 In other words, the Federal Circuit's view was that the problem addressed by the prior art and the claimed invention must have been the same. In the case at bar, the Federal Circuit observed, Asano did not address the same problem as the patent in suit. "The objective of the [Teleflex] '565 patent was to design a smaller, less complex, and less expensive electronic pedal assembly. The Asano patent, on the other hand, was directed at solving the 'constant ratio problem.' "596 The Federal Circuit thus held that the required TSM to combine Asano and the other prior art references was lacking, and accordingly vacated the district court's summary judgment of invalidity for obviousness.597

The Supreme Court reversed, concluding that the Federal Circuit had applied too rigid an approach to the TSM test in a manner contrary to Supreme Court patent precedent. Although the TSM test can serve as a "helpful insight" in analyzing nonobviousness,598 the Federal Circuit's conception of TSM in the case at bar was simply too narrow. Specifically, the appellate court had erred by

holding that courts and patent examiners should look only to the problem the patentee was trying to solve. . . . The question is not whether the combination was obvious to the patentee but whether the combination was obvious to a person with ordinary skill in the art. Under the correct analysis, any need or problem known in the field of endeavor at the time of invention and addressed by the patent can provide a reason for combining the elements in the manner claimed. 599

[B] Common Sense

The Supreme Court in KSR also emphasized the role of common sense, which teaches "that familiar items may have obvious uses beyond their primary purposes, and in many cases a person of ordinary skill will be able to fit the teachings of multiple patents together like pieces of a puzzle."600

Although a fact finder should avoid "the distortion caused by hindsight bias and must be cautious of argument reliant upon ex post reasoning,"601 there is no ground for denying the fact finder access to his common sense. "Rigid preventative rules that deny factfinders recourse to common sense . . . are neither necessary under [the Supreme Court's] case law nor consistent with it."602

Application of common sense to the facts of KSR required rejecting patentee Teleflex's contention that a PHOSITA hoping to make an adjustable electronic pedal would have ignored the Asano patent because it focused on a different problem. Rather, the Court viewed Asano as providing an "obvious example" of an adjustable pedal with a fixed pivot point, and other prior art indicated that a fixed pivot point was the ideal location to mount a sensor. "A person of ordinary skill is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton,"603 the Court observed. Design incentives and market forces can prompt variations of a known item, either in the same field or a different one. "If a person of ordinary skill can implement a predictable variation, §103 likely bars its patentability."604

After the Supreme Court's KSR decision, the Federal Circuit revisited the role of "common sense" in Perfect Web Tech., Inc. v. InfoUSA, Inc.605 Perfect Web's U.S. Patent No. 6,631,400 was directed to methods of distributing bulk e-mail to groups of targeted consumers. The invention involved "comparing the number of successfully delivered e-mail messages in a delivery against a predetermined desired quantity, and if the delivery [did] not reach the desired quantity, repeating the process of selecting and e-mailing a group of customers until the desired number of delivered messages ha[d] been achieved."606 A representative claim recited

1. A method for managing bulk e-mail distribution comprising the steps:

(a) matching a target recipient profile with a group of target recipients;

(b) transmitting a set of bulk e-mails to said target recipients in said matched group;

(c) calculating a quantity of e-mails in said set of bulk e-mails which have been successfully received by said target recipients; and,

(d) if said calculated quantity does not exceed a pre-scribed minimum quantity of successfully received e-mails, repeating steps (A)-(C) until said calculated quantity exceeds said prescribed minimum quantity.

A district court found that steps (a)-(c) of the claimed method where known in the prior art. The district court interpreted step (d) as "merely the logical result of common sense application of the maxim 'try, try again,' " and on this basis "found step (D) obvious."607

The Federal Circuit in Perfect Web affirmed the district court's decision that the asserted claims were invalid as obvious under §103. In reaching its decision the Federal Circuit extensively discussed the meaning of "common sense" as evolved in Federal Circuit case law and articulated by the Supreme Court in KSR. The appellate court explained that in its 2002 decision in In re Lee,608 it had "required the PTO to identify record evidence of a teaching, suggestion, or motivation to combine references because 'omission...

To continue reading

Request your trial