Chapter §9.02 Historical Background

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§9.02 Historical Background

[A] Hotchkiss v. Greenwood and the Elusive Requirement for "Invention"

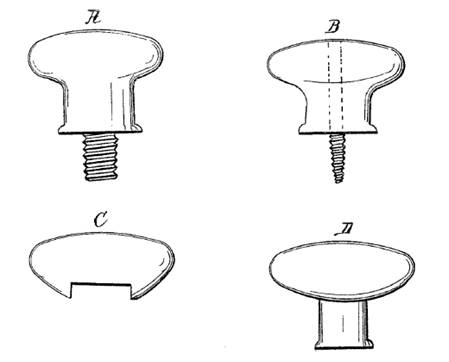

The U.S. Supreme Court in 1850 first required something more than novelty as a condition of patentability. At issue in Hotchkiss v. Greenwood33 was the validity of a patent claiming a mechanical combination of doorknob, shank, and spindle, shown in Figure 9-1:

Forming the doorknob of clay or porcelain was the novel feature of the combination. Earlier doorknobs had been made of wood, which was susceptible to warping and cracking, or of metal, which tended to rust from exposure to the elements. The patentee's substitution of materials resulted in a more attractive doorknob that was less expensive to manufacture and more durable than conventional doorknobs.34

Despite this seemingly significant and beneficial advance in the manufacture of doorknobs, the Hotchkiss majority held the patent invalid on the basis that no patentable "invention" resided in the mere substitution of clay for wood:

But this [substitution], of itself, can never be the subject of a patent. No one will pretend that a machine, made, in whole or in part, of materials better adapted to the purpose for which it is used than the materials of which the old one is constructed, and for that reason better and cheaper, can be distinguished from the old one; or, in the sense of the patent law, can entitle the manufacturer to a patent.

The difference is formal, and destitute of ingenuity or invention. It may afford evidence of judgment and skill in the selection and adaptation of the materials in the manufacture of the instrument for the purposes intended, but nothing more. 35

With these words, the Supreme Court's Hotchkiss decision gave rise to a vague and ambiguous requirement for "invention," representing some abstract, elusive quality beyond mere novelty. This ill-defined term of art proved incapable of precise application; the Court later admitted that "the truth is the word ['invention'] cannot be defined in such manner as to afford any substantial aid in determining whether a particular device involves an exercise of the inventive faculty or not."36 The circularity of the Hotchkiss analysis meant that to be patentable, an invention had to involve invention!

The lower courts struggled to apply the Hotchkiss formulation. They devised various tests and rules for what did, and did not, qualify as invention.37 The nebulous concept of invention became "the plaything of the judiciary."38 Impractical as the invention terminology was, it took firm root in the patent law lexicon and was not finally banished for over 100 years after the Supreme Court's decision in Hotchkiss. In the landmark 1952 Patent Act, the vague notion of invention was replaced by the modern concept of nonobviousness as set forth in 35 U.S.C. §103.39

[B] The Hotchkiss "Ordinary Mechanic"

Although the terminology it espoused is now seen as outdated and inaccurate, Hotchkiss v. Greenwood nevertheless remains fundamental to understanding the perspective from which the requirement for nonobviousness must be assessed. The Supreme Court in Hotchkiss made clear that an invention created with no more skill or ingenuity than that possessed by an "ordinary mechanic," working in the technology of the invention, did not merit a patent:

[U]nless more ingenuity and skill in applying the old method of fastening the shank and the knob were required in the application of it to the clay or porcelain knob than were possessed by an ordinary mechanic acquainted with the business, there was an absence of that degree of skill and ingenuity which constitute essential elements of every invention. In other words, the improvement is the work of the skillful mechanic, not that of the inventor. 40

The Hotchkiss "ordinary mechanic" metaphor proved a useful reference point for determining patentability, and today can be understood as the legal ancestor of the hypothetical person having ordinary skill in the art in 35 U.S.C. §103. To qualify for a patent under §103, an invention must not have been obvious to this hypothetical person, possessed of ordinary (not extraordinary) skill in the art (i.e., the technology) of the invention, at the time that the invention was made (i.e., at the "invention date"41).42 Under Hotchkiss (and current law), determining whether an invention represents enough of an advance to deserve patent protection requires a "functional approach [that involves] a comparison between the subject matter of the patent, or patent application, and the background skill of the calling."43

[C] Replacing "Invention" with Nonobviousness

One of the most significant advances in the history of the U.S. patent system was the 1952 elimination of the vague requirement for "invention" and its replacement by a statutory standard for "nonobviousness," codified in 35 U.S.C. §103. The Supreme Court in 1966 considered the new statutory standard for the first time in Graham v. John Deere Co.44

[1] Patent Act of 1952

[a] Enactment of §103

Prior to the March 16, 2013 effective date of §3(c) of the America Invents Act of 2011, 35 U.S.C. §103 consisted of three subsections. Post-AIA, it consists of only one, which applies to all types of inventions.45 The current version of §103 provides:

A patent for a claimed invention may not be obtained, notwithstanding that the claimed invention is not identically disclosed as set forth in section 102, if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains. Patentability shall not be negated by the manner in which the invention was made. 46

The original version of this statutory language was included in the 1952 Patent Act at the behest of its co-authors, then-patent attorney Giles Rich and Patent Office representative Pasquale Federico. The language reflects the frustration of the patent bar with the traditional invention standard of Hotchkiss, which had proved so vague and ambiguous as to be unworkable. Judges in different courts around the United States came to treat "invention" somewhat like obscenity, by applying an "I know it when I see it" type of analysis devoid of common guidelines or uniform analytical framework.47

After extensive lobbying, Rich, Federico, and others convinced Congress to enact legislation that would effectively abolish "invention" as a condition of patentability and replace it with a statutory requirement for nonobviousness. Thus, 35 U.S.C. §103 provides the modern-day counterpart to the Hotchkiss requirement for invention.48

[b] "Shall Not Be Negated"

The last sentence of the current (AIA-implemented) version of 35 U.S.C. §103 provides that "[p]atentability shall not be negated by the manner in which the invention was made."49 This simply means that an invention is no more obvious because it results from painstaking, long-running toil than from a "Eureka!" moment. In other words, the way in which an invention was accomplished cannot negate its patentability.

The drafters of the 1952 Patent Act included an earlier version of this language, "[p]atentability shall not be negatived . . ." (rather than "shall not be negated"), with the intent of legislatively overruling earlier statements by the Supreme Court that appeared to require a "flash of genius" for patentability.50 The resulting statutory language of §103 confirms the potential patentability of the products of incremental innovation, which modern scholars consider a primary model for innovation in many fields.51

[c] The "Person Having...

To continue reading

Request your trial