Chapter §23.03 Enforcement of Design Patents

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§23.03 Enforcement of Design Patents

The U.S. Supreme Court set forth the test for design patent infringement in the 19th century.76 That test continues to control today, despite more recent expansions and contractions by the Federal Circuit as described in the following subsections.

[A] "Ordinary Observer" Test of Gorham v. White (U.S. 1871)

The leading Supreme Court case on design patents, Gorham Co. v. White,77 established that design patent infringement must be assessed from the perspective of an "ordinary observer." The ordinary observer is not an expert in the manufacture of designs but rather a hypothetical purchaser or observer

of ordinary acuteness, bringing to the examination of the article upon which the design has been placed that degree of observation which men of ordinary intelligence give. It is persons of the latter class who are the principal purchasers of the articles to which designs have given novel appearances, and if they are misled, and induced to purchase what is not the article they supposed it to be . . . the patentees are injured, and that advantage of a market which the patent was granted to secure is destroyed. 78

Given that perspective, the Gorham Court held that the following test governs whether a design patent has been infringed:

[I]f, in the eye of an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other, the first one patented is infringed by the other. 79

As described infra, the en banc Federal Circuit reaffirmed the Gorham test's applicability in 2008.80

[B] Discarded "Point of Novelty" Component

After the Federal Circuit's creation in 1982, the appellate court expanded the test for design patent infringement by adding a second prong to the Gorham test. In addition to satisfying substantial similarity of the claimed and accused designs, the design patent holder also had to establish that the accused design appropriated the novel feature(s) of the patented design.81

As evolved by a series of Federal Circuit decisions,82 this additional "point of novelty" component to the design patent infringement analysis proved problematic because it mixed concepts of design patent validity with infringement. The point of novelty inquiry effectively required a patentee to affirmatively establish the novelty of its presumptively valid design.

[C] Modern Standard: Egyptian Goddess (Fed. Cir. 2008) (en banc)

In 2008, the Federal Circuit went en banc in Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc. to clarify the standard for infringement of design patents.83 The court rejected a freestanding point of novelty inquiry as a separate part of the standard.84

Rather, the infringement test should be applied as a single inquiry, that is, whether the Gorham ordinary observer would find the claimed and accused designs substantially similar. The Federal Circuit emphasized that the "ordinary observer" test is "the sole test for determining whether a design patent has been infringed."85 Under that test, "infringement will not be found unless the accused article 'embod[ies] the patented design or any colorable imitation thereof.' "86

The Egyptian Goddess en banc court explained further that the "ordinary observer" may sometimes be informed by knowledge of the prior art. For example, in cases where the claimed and accused designs do not appear "plainly dissimilar," the question whether an ordinary observer would determine that the two designs are substantially the same will benefit from comparing both designs with the prior art. The Federal Circuit observed that "[w]here there are many examples of similar prior art designs . . . , differences between the claimed and accused designs that might not be noticeable in the abstract can become significant to the hypothetical ordinary observer who is conversant with the prior art."87 In short, the prior art may provide an important context or frame of reference for assessing how similar the claimed and accused designs truly are.

Although the Federal Circuit's characterization of the "ordinary observer" to include a person aware of the prior art may suggest that the Egyptian Goddess test is not so very different from the rejected two-pronged test that included a point of novelty component, an important practical difference exists. Under the test for design patent infringement as formulated in Egyptian Goddess, the burden of proof to introduce any prior art that may have relevance to the infringement inquiry is placed on the accused infringer rather than the patentee.88 This result is consistent with the principle that a design patent, like a utility patent, is presumed novel,89 and the burden of invalidating the patent (e.g., on the basis of prior art that would render the claimed design anticipated or obvious) always remains on the accused infringer/validity challenger.

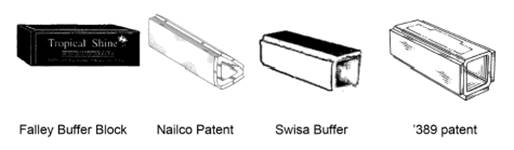

The patented design in Egyptian Goddess was that of a four-sided fingernail file or buffer featuring a hollow, square cross-section plus raised strips of nail buffing material on three of its four sides. The accused design incorporated buffing material on all four sides of a nail buffer. The prior art buffers (of square and triangular cross-sections) also included buffing material on all sides. Figure 23-6 depicts the claimed and accused buffers along with the closest prior art nail buffer designs.

The Federal Circuit framed the infringement question in Egyptian Goddess as "whether an ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art Falley and Nailco designs, would be deceived into believing the Swisa buffer is the same as the patented buffer."90 Answering that question in the negative, the Federal Circuit affirmed a district court's entry of summary judgment of no infringement. Although the patented and accused buffers had the same general shape (hollow and square in cross-section), the absence of buffer material on the fourth side of the claimed design could not be considered a minor feature in view of the closest prior art, which featured buffer material on all sides. An ordinary observer would likely regard the accused design as being closer to the prior art than the patented design.91 The Federal Circuit concluded that "[i]n light of the similarity of the prior art buffers to the accused buffer . . . no reasonable fact-finder could find that [the patentee, Egyptian Goddess] met its burden of showing . . . that an ordinary observer, taking into account the prior art, would believe the accused design to be the same as the patented design."92

[D] Illustrative Decisions After Egyptian Goddess

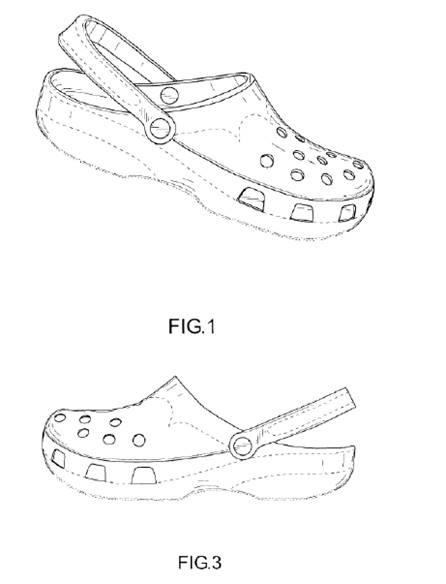

The Federal Circuit's 2010 decision in Crocs, Inc. v. Int'l Trade Comm'n93 illustrates how an overly detailed and partially incorrect verbal translation of a pictorial design claim resulted in an erroneous determination of design patent infringement. In 2006, Crocs, Inc. ("Crocs") brought a Section 337 complaint in the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) against a number of firms that imported imitations of the well-known CROCS brand casual shoes.94 Crocs alleged infringement of, inter alia, the ornamental footwear design claimed in its U.S. Patent No. D517,789 ('789 patent). Figure 23-7 depicts two views of the '789 design.

The ITC administrative judge provided the following detailed verbal claim construction of Crocs' design

In summary, when the '789 patent is considered as a whole, the visual impression created by the claimed design includes: footwear having a foot opening with a strap that may or may not include any patterning, is attached to the body of the footwear by two round connectors, is of uniform width between the two round connectors, has a wrench-head like shape at the point of attachment, and extends to the heel of the shoe; with round holes on the roof of the upper placed in a systematic pattern; with trapezoid-shaped holes evenly spaced around the side-wall of the upper including the front portion; with a relatively flat sole (except for upward curvature in the toe and heel) that may or may not contain tread on the upper and lower portions of the sole, but if tread exists, does not cover the entire sole, and scalloped indentations that extend from the side of the sole in the middle portion that curve toward each other. 95

Based on this claim construction, the administrative judge found that certain accused shoes did not infringe because their straps were not of uniform thickness, and certain other accused shoes did not infringe because their toe holes were not evenly spaced apart.96 The full ITC affirmed the administrative judge's determination of no infringement.

Reviewing the ITC's decision in Crocs, Inc., the Federal Circuit first cautioned the agency against "excessive reliance on a detailed verbal description in a design infringement case."97 The appellate court observed that "[i]n many cases, the considerable effort in fashioning a detailed verbal description does not contribute enough to the infringement analysis to justify the endeavor. . . . Depictions of the claimed design in words can easily distract from the proper infringement analysis of the ornamental patterns and drawings."98

The Federal Circuit determined that in the case at bar, the administrative judge's focus on individual features improperly led it away from considering the Crocs design as a whole. Moreover, the ITC administrative judge's verbal translation of the design claim erroneously included two details that were not required by the '789 patent drawings: (1) a strap of uniform width; and (2) holes evenly spaced around the sidewall of the upper. The judge had incorrectly focused on these details so as to create a "mistaken checklist" for infringement. The Federal Circuit viewed the...

To continue reading

Request your trial