Chapter §23.02 Requirements for Design Patentability

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§23.02 Requirements for Design Patentability

A design patent protects the "new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture",14 for example, the unique external appearance of a digital music player,15 a line of furniture,16 an automobile fender, or even a roofing shingle. Patentable designs must also satisfy the nonobviousness requirement of 35 U.S.C. §103.17 Each of these requirements is addressed below.

[A] Primarily Ornamental

The protection afforded by a design patent is limited to the overall ornamental, visual appearance of a product's design. Such protection cannot encompass designs that are primarily functional (i.e., in which the nature of the design is driven by the operation or performance of the underlying article).18 For example, the existence of a design patent on a golf club would not prevent others from copying features such as the streamlined shape of the club head, if this shape (although pleasing to look at, especially for golf aficionados) also increased the loft and distance of the golf ball. In this respect, design patent law adopts a nonfunctionality criterion analogous to the useful article doctrine of copyright law.19

Care must be taken to distinguish the functionality of the underlying article of manufacture from the alleged functionality of its external design. For example, in Avia Group Int'l, Inc. v. L.A. Gear Cal., Inc.20 the Federal Circuit upheld the validity of two athletic shoe design patents over arguments by the accused infringer that the designs were primarily functional rather than ornamental as required by 35 U.S.C. §171. The appellate court did not dispute that "shoes are functional and that certain features of the shoe designs in issue perform functions."21 However, if functionality of the underlying article is not separable from the alleged functionality of its design, "it would not be possible to obtain a design patent on a utilitarian article of manufacture . . . or to obtain both design and utility patents on the same article."22

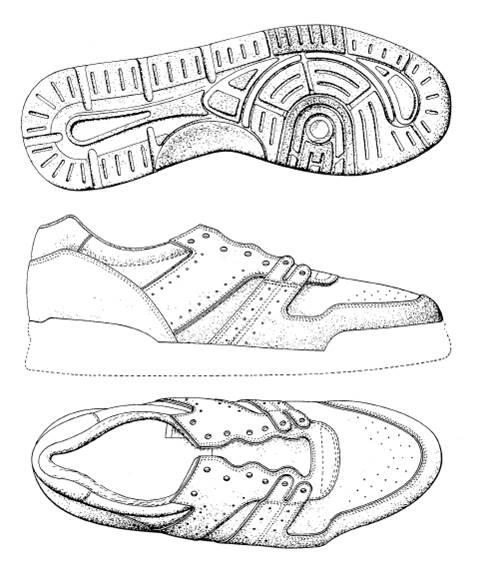

Moreover, the patentability of a claimed design must be considered as a whole; that is, focusing on its overall appearance. The Federal Circuit in Avia Group agreed with the district court that the patented designs in question, directed to certain aesthetic aspects of an athletic shoe's outer sole and its upper,23 were primarily ornamental. The designs encompassed features such as the location and arrangement of perforations and stitching in the shoe upper, as well as a "swirl effect" around the pivot point on the sole of the shoe, as depicted in Figure 23-1.24 Moreover, to the extent that the design features performed the functions suggested by the defendants, the Federal Circuit found persuasive the district court's reasoning that all such functions could have been performed by many other possible design choices.25

[B] Novelty

A patentable design must be "new,"26 or (in patent parlance) novel. The Federal Circuit evaluates the novelty of designs (in other words, determines whether claimed designs are "anticipated" by the prior art) under a "substantially similar" test—whether the claimed design is substantially the same as the prior art design.27 This is the same test that is applied to determine infringement of design patents, as described infra.28

Notably, the "substantial similarity" standard to assess the novelty of design inventions is a different standard from that of "strict identity" applied to analyze novelty for utility inventions.29 The use of a "substantial similarity" standard for design anticipation (i.e., the negation of novelty) most likely follows from application of the patent law maxim, "that which infringes if later in time anticipates if earlier in time."30

In the view of this author, however, the use of a "substantial similarity" standard rather than a strict identity standard for design anticipation runs contrary to the preamble of 35 U.S.C. §103, which refers to the possibility that a claimed invention would have been obvious "notwithstanding that the claimed invention is not identically disclosed as set forth in section 102. . . ."31 In other words, §103 implies that §102 mandates an identicality requirement to negate novelty. But this author's view of the matter does not comport with the case law.

[C] Nonobviousness

Patentable designs must satisfy the nonobviousness requirement of 35 U.S.C. §103, which is implicitly incorporated into the design provision, 35 U.S.C. §171.32 The case law discussed in the following subsections instructs on the proper perspective for and method of analyzing the nonobviousness of designs.

[1] Designer of Ordinary Skill Perspective

The nonobviousness of a claimed design must be judged from the perspective of a hypothetical person of ordinary skill in the art, as is the nonobviousness of a utility invention under 35 U.S.C. §103. The Federal Circuit explained in Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., Inc.33 that "specifically, the inquiry is whether one of ordinary skill would have combined teachings of the prior art to create the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design."34 In the design realm, however, the Federal Circuit holds that that hypothetical person is "one who designs articles of the type involved."35 In short, the nonobviousness of designs is judged from an "ordinary designer" perspective.

In the view of this author, the use of a "designer of ordinary skill" perspective to assess the validity of a design creates cognitive dissonance in design patent law. As discussed infra,36 whether a design patent has been infringed is evaluated from a different perspective—that of a hypothetical "ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives. . . ."37 The Supreme Court explicitly rejected the notion that an "expert" should compare two designs for purposes of determining infringement.38 Rather, the correct perspective for design infringement is that of an ordinary "purchaser" or consumer of the designed articles, not a designer thereof.

The use of two different perspectives to assess design validity and design infringement appears to violate the policy of parallelism in considering questions of validity and infringement.39 Nevertheless, the dichotomy stands. In 2013, the Federal Circuit in High Point Design LLC v. Buyers Direct, Inc.40 reversed a district court for applying an "ordinary observer" standard rather than an "ordinary designer" standard to assess design nonobviousness.41

[2] Two-Step Analysis for Combining Design Prior Art

The analysis for evaluating design nonobviousness involves combining the teachings of prior art references, as is also the case when determining whether a utility invention would have been obvious.42 The ultimate inquiry is "whether one of ordinary skill would have combined teachings of the prior art to create the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design."43

The Federal Circuit in Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., Inc.44 parsed this overall inquiry as requiring a two-step approach. First, "[b]efore one can begin to combine prior art designs, . . . one must find a single reference, 'a something in existence, the design characteristics of which are basically the same as the claimed design.' "45 Patent attorneys commonly refer to this single reference as the "primary" or "Rosen" reference.

Second, "[o]nce th[e] primary reference is found, other references may be used to modify it to create a design that has the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design."46 These other or "secondary" references "may only be used to modify the primary reference if they are 'so related [to the primary reference] that the appearance of certain ornamental features in one would suggest the application of those features to the other.' "47

Many design patent nonobviousness cases turn on whether the challenger has satisfied the first step; that is, whether the validity challenger has identified prior art that is "close enough" to qualify as a primary reference. For example, the validity challenger/accused infringer in Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., Inc.48 did not meet this burden. The patent in suit in Durling was generally directed to the design for a sectional sofa group with a corner table and integral end tables, as shown in Figure 23-2:49

The admittedly closest prior art was the design of a sectional sofa manufactured by Schweiger Furniture Industries ("Schweiger"), as shown in Figure 23-3:

A district court invalidated Durling's patent based on its finding that the differences between the claimed and prior art designs were insignificant.50 In the district court's view, the main difference between Durling's design and the Schweiger prior art design was that the former had somewhat less vertical support (i.e., the extent to which the base extended under the end tables).

The Federal Circuit in Durling reversed. The appellate court agreed with patentee Durling that although the prior art Schweiger sofa and Durling's design shared the same basic design concept, i.e., a sectional sofa with integrated end tables, Schweiger's design did not create the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design.51 Thus Schweiger did not qualify as a primary reference on which to base a conclusion of obviousness.

The Federal Circuit first explained that identifying a primary reference in a design case requires a trial court to:

(1) discern the correct visual impression created by the patented design as a whole; and (2) determine whether there is a single reference that creates "basically the same" visual impression. In comparing the patented design to a prior art reference, the trial court judge may determine almost instinctively whether the two designs create basically the same visual impression....

To continue reading

Request your trial