Chapter §2.04 Claim Definiteness Requirement

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§2.04 Claim Definiteness Requirement

[A] Statutory Basis: 35 U.S.C. §112(b)

Section 112(b) of the Patent Act requires that each patent conclude with one or more claims that particularly point out and distinctly claim the subject matter that the applicant regards as his invention.147 Although the statute does not use the word "definite," this statutory condition has come to be known to patent practitioners as the claim definiteness requirement.

The Federal Circuit treats a determination that a patent claim is invalid for failing to meet the definiteness requirement of 35 U.S.C. §112(b) as a legal question subject to the de novo standard of review.148

In Sonix Tech. Co. v. Publications Int'l, Ltd.,149 the Federal Circuit clarified that in view of the Supreme Court's 2015 decision on review of district court patent claim construction in Teva Pharm. USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc.,150 the ultimate determination of claim definiteness under §112, second paragraph is reviewed de novo, but any underlying factual findings by the district court based on extrinsic evidence are reviewed for clear error in accordance with Teva.151 In the Sonix case, however, although the district court reviewed extrinsic evidence (e.g., the parties' experts' deposition testimony) on the issue of definiteness, the district court's conclusions (reversed by the Federal Circuit) that the challenged claim term ("visually negligible") was subjective and lacked an objective standard were not findings of fact subject to clear error review. Instead, "they [we]re conclusions relating to the meaning of the intrinsic evidence, and whether it convey[ed] claim meaning with reasonable certainty."152 Such conclusions cannot be transformed into findings of fact merely because an expert offered an opinion on them, the Circuit cautioned.

[B] Perspective for Determining Claim Definiteness

In satisfying the statutory requirement that patent claims "particularly point out and distinctly claim the subject matter which the applicant regards as his invention,"153 whose perspective should be used determine whether the claim language is sufficiently "particular" and "distinct"? The proper vantage point is that of the hypothetical PHOSITA, who is also encountered in many other patent law contexts.

Patent claims are not interpreted according to what a judge, jury, or even the inventor may understand the terms of the claim to mean. Rather, one must determine whether the claim terms are definite to a PHOSITA, a hypothetical construct that represents the skill and understanding of an "ordinary" person (e.g., whether a scientist, engineer, technician, or other worker) in the particular technology of the claimed invention.154

Solomon v. Kimberly-Clark Corp.155 aptly illustrates this rule. Solomon's patent was directed to a disposable woman's protective undergarment for holding a feminine napkin. The accused infringer, Kimberly-Clark, alleged that the patent was invalid under 35 U.S.C. §112, ¶2 because Solomon failed to claim the subject matter that she regarded as her invention. This argument was based on Solomon's deposition, in which she stated that the "depression" limitation of the claimed invention had a uniform thickness.156 However, the district court (and on appeal, the Federal Circuit) interpreted the claim language to mean that the depression had a thickness that varied, contrary to Solomon's deposition testimony.

The Federal Circuit rejected Kimberly-Clark's challenge and upheld the validity of the patent claims under §112, ¶2. The definiteness of claims of an issued patent must be evaluated from the perspective of the PHOSITA, the court explained, and not based on evidence extrinsic to the patent such as the inventor's deposition testimony. The inventor's perspective may not be the same as that of the PHOSITA. If the claims of the patent, read in light of the written description, would reasonably give notice to the PHOSITA of the scope of the patentee's right to exclude others, this is all that the definiteness rule of §112, ¶2 requires.157 After a patent issues, statements by the inventor about what she subjectively intended or understood the claim language to mean are largely irrelevant, the court emphasized. After issuance, the claims must be viewed objectively, from the perspective of the hypothetical PHOSITA.158

[C] Definiteness Standards: Nautilus v. Biosig (U.S. 2014)

The definiteness requirement " 'ensure[s] that the claims delineate the scope of the invention using language that adequately notifies the public of the patentee's right to exclude.' "159 Thus, a PHOSITA must be able to "understand what is claimed."160

The U.S. Supreme Court examined and restated the Federal Circuit's formulation of the patent claim definiteness standard in the important 2014 decision, Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc.,161 detailed below. Prior to the Supreme Court's 2014 Nautilus decision, Federal Circuit standards for claim definiteness were quite lenient. The appellate court's decisions suggested that whether a PHOSITA would understand what was claimed for purposes of assessing definiteness essentially equated to determining whether the patent's claims could be interpreted.162 Before Nautilus, the definiteness requirement of 35 U.S.C. §112, ¶2 (renamed 35 U.S.C. §112(b) by the America Invents Act of 2011) was considered unsatisfied only if the claim terms in question were " 'not amenable to construction or [we]re insolubly ambiguous. . . ."163 The Federal Circuit observed that claim terms were sufficiently definite if they could "be given any reasonable meaning."164 Even if the claim construction task was difficult, this did not necessarily render the claim language indefinite.165 Because reasonable persons could frequently disagree over patent claim construction, proof of in definiteness had to " 'meet an exacting standard.' "166 In sum, prior to the Supreme Court's 2014 Nautilus decision, the standard of claim definiteness was not difficult to satisfy in many cases.167

The Supreme Court in 2014 rejected the Federal Circuit's lenient approach to satisfying the claim definiteness requirement. In Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc.,168 the Court explained that the Circuit's "not amenable to construction" or "insolubly ambiguous" standards "lack[ed] the precision that §112, ¶ 2 demands," and had the potential to confuse the lower courts.169 "To tolerate imprecision just short of that rendering a claim 'insolubly ambiguous' would diminish the definiteness requirement's public-notice function and foster the innovation-discouraging 'zone of uncertainty' . . . against which this Court has warned."170

Rather, the Supreme Court in Nautilus "read §112, ¶ 2 to require that a patent's claims, viewed in light of the specification and prosecution history, inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention with reasonable certainty."171 The Court's "reasonable certainty" test found its roots in precedent requiring a "reasonable" degree of certainty in patent claims,172 recognizing that absolute precision in setting forth the boundaries of the patentee's right to exclude is not attainable.173

The Nautilus Court's "reasonable certainty" test aimed to "reconcile concerns that tug in opposite directions."174 The Court realized, firstly, that the definiteness requirement "must take into account the inherent limitations of language."175 Contrariwise, patents must also be precise enough to afford clear notice to the public of what subject matter is encompassed by the claims and what subject matter remains open.176 The Court additionally observed that without a "meaningful definiteness check," patent applicants faced "powerful incentives to inject ambiguity into their claims."177 The Nautilus Court's new test of "reasonable certainty" about claim scope for those of skill in the art purported to reconcile these opposing policies in a manner that "mandates clarity, while recognizing that absolute precision is unattainable."178

At issue in the Nautilus dispute (captioned Biosig v. Nautilus, Inc. below179) was Respondent Biosig Instruments' 5,337,753 ('753 patent), which concerned a heart rate monitor for use with an exercise machine. The monitor improved on the prior art by eliminating certain noise signals during the detection of a user's heart rate. In particular, the claimed monitor eliminated signals given off by the user's skeletal muscles (electroyogram or "EMG" signals) when the user moved her arms or squeezed her fingers. A problem existed because EMG are the same frequency as electrocardiograph (ECG) signals generated by the user's heart. Thus EMG signals could mask the ECG signals desired to be measured. The claimed invention provided structure and circuitry that substantially removed the unwanted EMG signals.180

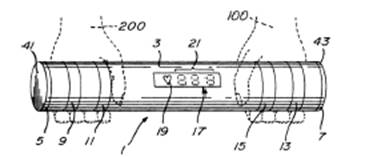

The '753 patent disclosed a heart-rate monitor contained in a hollow cylindrical bar (like those typically present on treadmills or exercise bikes). A user would grip the cylindrical bar with both hands, such that each hand came into contact with two electrodes, one referred to as the "live" electrode and the other the "common" electrode. Importantly, claim 1 of the '753 patent required that on each half of the cylinder, the live and common electrodes be mounted "in a spaced relationship" with each other.181 An embodiment of the '753 patent is shown in Figure 2-6:

The Southern District of New York was able to construe the '753 patent's disputed claim 1 phrase "spaced relationship" to mean that there was " 'a defined relationship between the live electrode and the common electrode on one side of the cylindrical bar and the same or a different defined relationship between the live electrode and the common electrode on the other side of the cylindrical bar.' "182 Nevertheless, the district court held Biosig's patent claims invalid for indefiniteness. In the district court's view, the patentee...

To continue reading

Request your trial