Chapter §2.01 Introduction

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§2.01 Introduction

[A] Statutory Basis: 35 U.S.C. §112(b)

This chapter focuses on claims, arguably the most important part of a patent. A patent claim is a precision-drafted, single-sentence definition of the patent owner's right to exclude others.1 Every U.S. utility patent must conclude with

one or more claims particularly pointing out and distinctly claiming the subject matter which the applicant regards as his invention. 2

Claims have been required by statute in U.S. patents since 1870,3 although the manner in which claims are drafted and interpreted has evolved significantly since that time. This treatise introduces the theory and practice of patent claiming in Chapter 2 because of the topic's central importance to all concepts addressed in the remaining chapters. The task of patent claim interpretation, integral to patent litigation, is analyzed in further detail in Chapter 15 of this treatise.

[B] The Paramount Role of Patent Claims

Claims play a central role in all aspects of the U.S. patent system. For example, the U.S. Patent and Trade Office (USPTO) examines the claims and compares them to the prior art to determine whether an applicant's invention, as claimed, merits patent protection. When determining validity and infringement in federal court litigation involving issued patents, the claims are the central focus of judges and juries. Patent licensing also involves understanding patent claims; for example, a royalty-bearing product may be defined in a license as only such products coming within the scope of the claims of a certain issued patent or pending patent application.4

The critical threshold step of interpreting the claims—that is, determining what the words in the claims mean and what scope they are entitled to—is quite often dispositive of the issues of infringement and validity.5 Hundreds of millions of dollars can turn on the meaning of a single word in a patent claim.6 Consequently, the crafting of patent claims is one of the most challenging and important drafting tasks in all of legal practice. This chapter, therefore, covers not only the legal doctrines pertaining to claim interpretation, but also a number of commonly used drafting techniques and claim formats.7 In patent law, "the name of the game is the claim."8

[C] Definition of a Patent Claim

A patent claim defines the scope of the patent owner's property right—that is, the extent of her right to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering to sell, or importing her invention, as claimed, in this country, during the term of the patent.9 Long-standing practice requires that a patent claim be written as single sentence, no matter how long; the sentence forms the object of the phrase "I claim" or "we claim."10 For example, the claims portion of a patent directed to a pencil might begin as follows:

We claim:

1. A pencil having an eraser fastened to one end. 11

Typically the patent would include additional claims, sequentially numbered 2 through n (n denoting the number of the last claim), reciting additional details about the pencil.12

A patent claim functions analogously to a real property (land) deed, in that the claim is intended to precisely define the boundaries of the property owner's right to exclude others. Taking the analogy a step further, the claim acts as a textual fence around the patentee's intangible property—the claimed invention.

A deed to real property typically sets forth the precise boundaries ("metes and bounds") of a plot of land.13 Importantly, this metes-and-bounds definition does not describe the interior of the land (e.g., whether the land is flat, hilly, wooded, boasts structures, or has water running through it). Likewise, it is fundamental that a patent claim does not describe the invention in terms of how to make and use it, or how to carry out the invention's best mode. Contrary to some authority, patent claims do not serve to explain an invention.14 That teaching or explanatory function is the role of the written description and drawings, parts of the patent document that are distinct from the claims.15

In fact, the invention or inventive contribution of the patent applicant is often a far cry from what is ultimately recited in the patent claims. This variance results from the vagaries of patent prosecution: patent applications are typically filed with an array of claims of varying scope ranging from very broad to very narrow. Over the course of the application's prosecution, the USPTO often will identify prior art that the agency believes would anticipate or at least render obvious the subject matter of the broadest claims. Unless she believes the rejections are appealable, the patent applicant (or her patent attorney or patent agent) may amend the claims, narrowing their scope to recite subject matter that would be novel and nonobvious over the cited prior art.16

In the course of their prosecution through the USPTO, the claims (which set forth the literal boundaries of the patentee's right to exclude others17) may evolve into something very different from the invention as originally envisioned by the inventor.18 As expressed by a prominent patent jurist:

What do we construe claims for, anyway? To find out what the inventor(s) invented? Hardly! Claims are frequently a far cry from what the inventor invented. In a suit, claims are construed to find out what the patentee can exclude the defendant from doing. CLAIMS ARE CONSTRUED TO DETERMINE THE SCOPE OF THE RIGHT TO EXCLUDE, regardless of what the inventor invented. I submit that that is the sole function of patent claims. I think this truism ought to be promoted in every seminar on the subject of claims. . . . Tell [readers] to stop talking about claims defining the invention. It's a bad habit. And it seems to be almost universal. 19

[D] Public Notice Function

Decisions of the Federal Circuit emphasize the critical role of patent claims in providing public notice of the scope of a patent owner's right to exclude.20 In theory, the public (and in particular, the patentee's competitors) should be able to read the claims in connection with the remainder of a patent and its prosecution history and understand the extent of the patent owner's right to exclude, without having to resort to litigation.21 To properly perform this public notice function, the language of patent claims must be definite as discussed infra.22

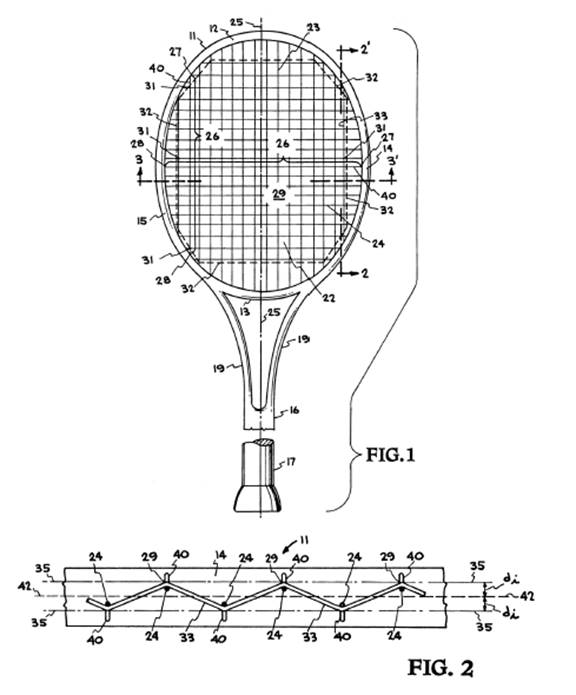

Satisfaction of the public notice function controlled interpretation of disputed claim language in Athletic Alternatives, Inc. v. Prince Mfg.23 Athletic Alternatives' (AAI's) patent was directed to the design of a tennis racket with splayed strings; that is, with string ends anchored to the racket frame alternately above and below the frame's central plane. Claim 1 of the patent required that an offset "distance di varies between minimum distances for the first and last string ends in said sequence and a maximum distance for a string end between said first and last string ends in said sequence."24 Figure 2-1 illustrates the AAI racket's design:

The parties disputed the meaning of the claim phrase "varies between." Accused infringer Prince Manufacturing contended that the phrase should be interpreted such that the offset distance di had to take on at least three values (i.e., a minimum, a maximum, and at least one intermediate value), the Prince racket having only two such offset distance values. Contrariwise, patentee AAI argued that "varies between" should be more broadly construed to read on the racket's splay pattern having two or more offset distances, rather than a minimum of three.

The Federal Circuit determined that the language of the claims themselves provided two equally plausible meanings for the disputed phrase (i.e., requiring either at least two offset distances, or at least three). The remainder of the patent and its prosecution history did not aid in the interpretation. The appellate court ultimately sided with accused infringer Prince's narrower interpretation, emphasizing public policy concerns.

Reviewing the history of claiming in U.S. patent practice, a majority of the Federal Circuit panel observed that the primary purpose of the requirement that inventions be distinctly claimed is " 'to guard against unreasonable advantages to the patentee and disadvantages to others arising from uncertainty as to their [respective] rights.' "25 The majority explained that

[w]ere we to allow [patentee] AAI successfully to assert the broader of the two senses of "[varies] between" against Prince, we would undermine the fair notice function of the requirement that the patentee distinctly claim the subject matter disclosed in the patent from which he can exclude others temporarily. Where there is an equal choice between a broader and a narrower meaning of a claim, and there is an enabling disclosure that indicates that the applicant is at least entitled to a claim having the narrower meaning, we consider the notice function of the claim to be best served by adopting the narrower meaning. 26

In accordance with its emphasis on the notice function performed by patent claims, the Federal Circuit determined that the disputed claim phrase "varies between" required at least three offset distances. Prince's accused tennis racket (having only two) did not literally infringe.27

[E] Peripheral Versus Central Claiming

The development of claiming practice in the United States reflects a shift from a historical central claiming regime to the current system of peripheral claiming.28 The evolution of U.S. patent claiming presages the courts' current focus on close reading of claims as precise delimiters of the patent property right.

The earliest U.S. patent claims were written in central claiming style, often in the form of "omnibus" or "formal" claims.29 Central claiming means that a claim recites the preferred embodiment of an invention but is understood to...

To continue reading

Request your trial