CHAPTER 17 The Development of Underground Injection Control Programs On Indian Lands: Issues, Challenges and a Blueprint For Tribal Program Development

| Jurisdiction | United States |

(Feb 1989)

The Development of Underground Injection Control Programs On Indian Lands: Issues, Challenges and a Blueprint For Tribal Program Development

Wind River Environmental Quality Commission

Fort Washakie, Wyoming

I. Introduction

The formal development of underground injection control (UIC) programs in Indian Country has been made possible by the 1986 amendments to the Safe Drinking Water Act (PL 99-339) and by the promulgation of formal rules by the Environmental Protection Agency (40 CFR parts 35-147). The rules set procedures for the treatment of tribes as States, the provision of technical assistance, the criteria for the receipt of agency funds and primacy approval, and a timeline for the development of tribal regulatory programs in the underground injection and public water supply supervision areas.

While promising to work with Tribes, however, the rules also contain regulatory exemptions and administrative restrictions which complicate the development and enforcement of a comprehensive regulatory framework. The purpose of this paper is to describe the current status of UIC activities in selected areas of Indian Country, to highlight the major challenges to tribes within this context, and to suggest a procedure for the development of tribal programs in the UIC area.

This paper also discusses some practical issues and challenges involved in the development of a tribal regulatory program for underground injection control. Clearly, underground injection control poses significant site-specific technical challenges that must act to sharpen the current EPA administered regulatory program. Moreover, there are institutional challenges and barriers to effective administration of programs involving to coordination of federal, state, tribal, local agencies and private individuals. Finally, there are challenges in the development of the internal tribal legal and technical mechanisms necessary to administer a program. Examples of current tribal programs are discussed, highlighting specific challenges, approaches used and structural components of each program.

[Page 17-2]

II. Underground Injection: Process & Regulatory Framework

The Process

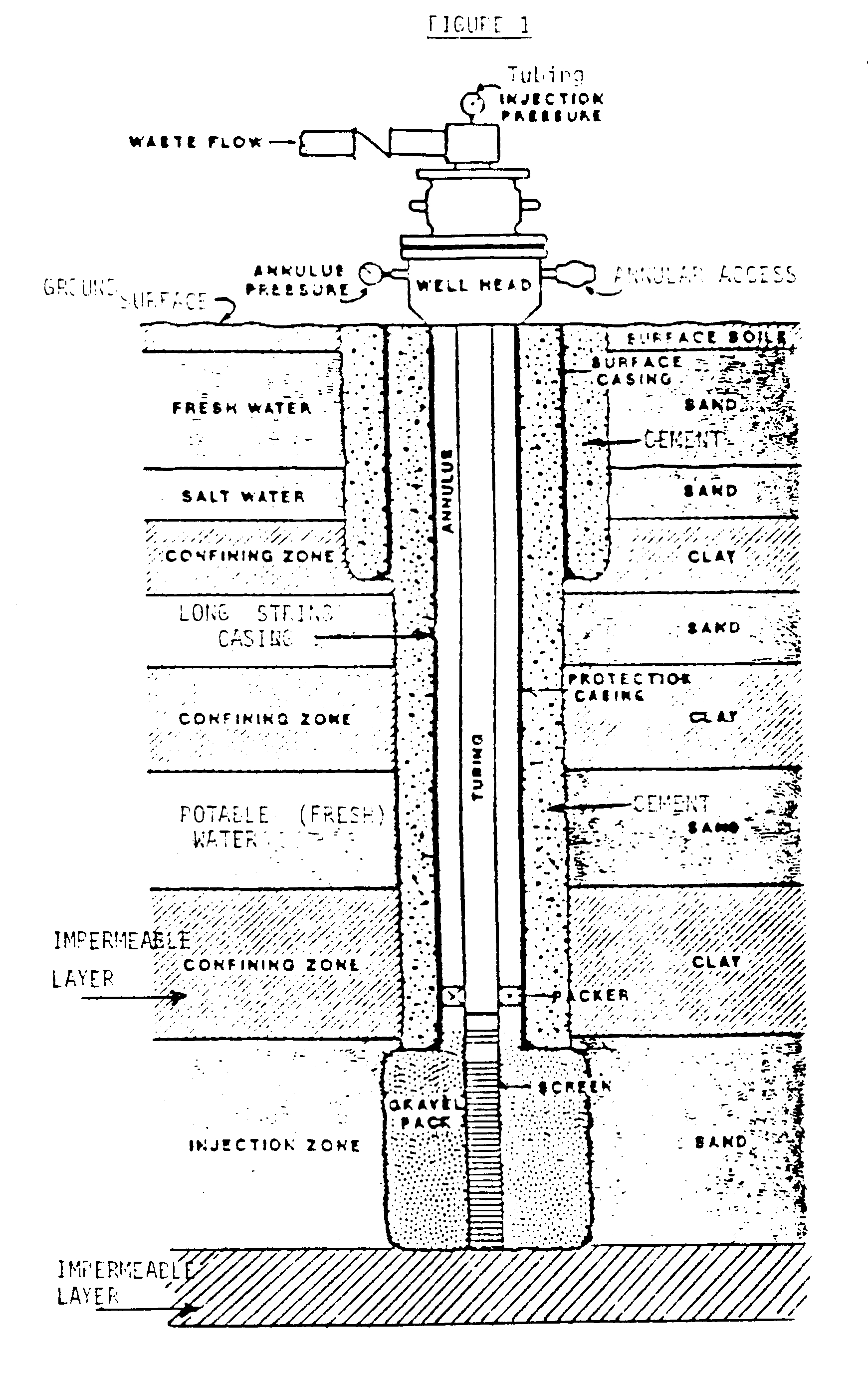

Controlled wastewater injection in the United States was first practiced in the 1920's in connection with oil and gas field operations. Many of these early operations occurred on Indian lands in Colorado, Wyoming, Oklahoma and in Texas. In these operations, oil field brines, or formation waters associated with oil fields, were injected back into the ground through former production wells for disposal and later for enhanced recovery of oil and gas, brine disposal and storage. Municipal and industrial disposal of wastes by injection through wells was first practiced in the 1940's but unregulated disposal of municipal and industrial wastes through shallow wells into strata containing potable ground water has been and still is practiced.1 However, most injection wells today are completed in units that are porous and permeable saline water-bearing rocks at great depth, vertically bounded by impermeable rock units. Currently, over 70% of hazardous waste disposal in the United States is practiced through underground injection2 . Figure 1 presents a schematic of a typical injection well and geologic setting.

When wastewater is injected into deep wells for disposal, it can pose a serious environmental threat unless the injection process is carefully planned and executed from start to finish. Environmental threats to ground water quality result from four general areas: (1) improper well construction and formation sealing, (2) injection of fluids at pressures which initiate formation fracturing and subsequent movement of fluid, (3) improper characterization and use of subsurface injection zones, and (4) injection of fluids sufficiently different in chemical quality from the formation fluids such that an initiation of clogging or solution (dissolving) of the rock or corrosion of the well casing is initiated. Because of the widely varying subsurface conditions in each major injection area, each of these factors must be evaluated on a site-specific basis as a prelude to the development of regulations regarding the management of underground injection.

Underground injection activities on Indian lands have been practiced for many decades, with varying degrees of regulation. After a considerable period of little regulation (1900-1965), underground injection activities have been managed by the U.S. Geological Survey (U.S.G.S.), the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and more recently, by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Indian tribes. Much additional regulation has occurred as a result of an increasing awareness of the potential problems associated with potential and known ground water contamination. However, jurisdictional conflicts have made difficult the development of comprehensive programs and actual monitoring.

For example, the information available for Indian lands regarding ground water aquifers—location, geometry, water quality, inter-aquifer movement, actual injection well performance, contamination incidents, long-term build up of dissolved

[Page 17-3]

[Page 17-4]

solids in ground water, and other factors—suffers as a result of jurisdictional uncertainty. These are critical factors in the development of regulatory programs, and Tribes must work to develop large amounts of data in order to have a base upon which to make regulatory decisions. In many situations, the increased data collection will result in the identification of wide-spread contamination and need for regulatory controls.3 After so many years of injection activity, it is amazing that so little information exists.

The Regulatory Framework

It is important to recognize that many Indian tribes are in the process of quantifying water rights under the Winters Doctrine 4 , and that much of the motivation for protection of the underground water resource arises from the need to protect all sources of water for the long term. Consequently, although there is a formal framework and procedure for UIC developed by EPA, the larger context in which this framework must operate is that of the tribe's operation as a sovereign and as manager of its natural resource base.

The regulatory framework for underground injection control is governed by 40 CFR sections 35, 124, 141, 142-147 of the Safe Drinking Water Act. The sections spell out the classification of injection well types, the requirements for program activity, including a permit process, well construction requirements, mechanical integrity testing, reporting and monitoring, public notification and participation. As was mentioned earlier, these sections also spell out the requirements for Indian participation in the SDWA programs, including the treatment as a state designation, required internal programmatic requirements for EPA funding, and time tables for the development of tribal primacy for UIC and Public Water System programs (PWS). As is well known, EPA has delegated primacy to several States under these programs.

EPA's Generic Program

For Indian lands, EPA has retained enforcement for all well types in the UIC program. The "generic program", as extended to all Indian lands across the country in 1987 and 1988, is outlined in Table 1. A flow chart depicting the permitting and appeals process under the generic scheme is presented in Figure 2.

[Page 17-5]

Table 1: Elements of EPA's Generic UIC Program, extended to Indian lands in 1987 and 1988

| Coverage and Scope: | Class I, II, III, IV and V injection wells |

| Construction, Operation, Management, Compliance, Enforcement | |

| Administration: | Agency |

| Public Participation Program (40 CFR Part 124) | |

| Notice | |

| Appeal | |

| Compliance Tracking & Enforcement (40 CFR Part 144.8) | |

| Reports | |

| Surveillance | |

| Enforcement | |

| Inventory | |

| Schedule & Priority for Issuing Permits | |

| Authorization to Inject Fluids: | Authorization by Rule (40 CFR Part 144-147) |

| Existing Class I, II, II wells, Class V awaiting regulations | |

| Authorization by Permit | |

| Technical Requirements for Permit Approval | |

| Aquifer Exemptions: | Criteria for Exemption of Aquifers |

| Application Procedure for Exemptions (40 CFR Part 146) | |

| Monitoring & Testing: | Well Construction Requirements |

| Mechanical Integrity Testing Frequency of Tests- 5 years | |

| Plugging and Abandonment | |

| Emergency Response: | Procedures, Capabilities, Fines |

[Page 17-6]

EPA Permitting Procedures

Omitted From Electronic Version

[Page 17-9]

Although the generic program theoretically provides a framework for the regulation of activities, in practice there are many difficulties. Problems arise in the areas of effective administration of the program, in the conditions required for permit approval, in actual compliance monitoring, and in collection and analysis of adequate data upon which to make decisions regarding aquifer exemptions.

Administrative Problems in the Generic Program

For example, EPA proposes to assume responsibility for programs which have been formerly under the auspices of other federal or state agencies. Often, the...

To continue reading

Request your trial