King John, Magna Carta and the Origins of English Legal Rights

| Publication year | 2015 |

| Pages | 0117 |

| Citation | Vol. 76 No. 2 Pg. 0117 |

Prelude

King John: treacherous, tyrannical, mercurial, malicious-the third ruler of the Angevin dynasty.1 John ruled England and a shrinking number of French provinces from the death of his brother, Richard Coeur de Lion, in April 1199, until his own death in October 1216. One historian observed: "The legend of his awfulness as a person as well as a ruler dates from his own lifetime." King John may have possessed good qualities-brilliant strategist, firm administrator, fiercely determined-but it was his tyranny that caused English barons to revolt against him. That clash led to a settlement, a peace treaty, Magna Carta. Thus, it was a tyrant king who, forced to deliberate with rebellious nobles, put his seal to Magna Carta, a foundation stone of English and American legal rights.

International Politics and John's Character

John was clever and unscrupulous, yet he had little success in the 13th century's Game of Thrones. His rival was the Capetian monarch, Philip II of France. Older than John, Philip viewed the Angevins as a constant threat, for they had acquired, through conquest or marriage, the territories of Normandy, Brittany, Anjou, Poitiers and Aquitaine. True, they owed Philip homage for these lands, but they were positioned to undermine his power.3 In response, Philip did what he could to divide and conquer. In the 1190s he supported John's unsuccessful effort to supplant King Richard. In the mid- to late 1190s, Philip warred with Richard, with little success. He was probably relieved to sign a peace treaty with John in 1200.4

John's behavior thereafter-notably his marriage in August 1200 to Isabella of Angouleme, the betrothed of Hugh of Lusignan-led to legal disputes in which Philip, infuriated over John's refusal to answer charges in person, confiscated all of his French lands.5 Dismissing John as a "contumacious" vassal, Philip bestowed upon Arthur of Brittany (John's nephew) all Angevin lands in France except for Normandy-which Philip wanted.6 In the ensuing war, John captured Arthur and then murdered him, allegedly in a drunken rage.7 Meanwhile, Philip, this time, made a better showing as a commander. By the fall of 1204, all of Normandy was in French hands, and most of John's Norman barons had switched sides.8

Fearing a French invasion of England, John decreed in January 1205 that he would mobilize his whole kingdom. Ever the fundraiser, John fitted out two expeditions: one to re-take Normandy and one to reinforce his vassals in Poitou and Aquitaine. English barons balked, though, at campaigning in a foreign land, and John was reduced to assisting his southwestern vassals with mercenary troops. By 1206, when he concluded a two-year truce with Philip, John saw his barons as a dangerous element.9 In coming years, as he endured and exploited a religious crisis, he would become a master manipulator of feudal relations.

God, Mammon And Law

In theory, no medieval king could afford to lose the cooperation of the archbishops, bishops and abbots who ruled over the vast landed holdings of the Catholic Church.10 Richard Coeur de Lion had enjoyed mutually beneficial relations with Hubert Walter, who held overlapping offices, including those of Archbishop (1194-1205), Justiciar (1193-1198), Papal Legate (1195-1198) and Chancellor (1199-1205). John made use of Hubert's talents but resented his prestige. When Hubert died in 1205, John was determined to place one of his familiars upon the arch-episcopal throne; he had already clashed unsuccessfully with the Pope, Innocent III, over a Norman bishopric.11

The monks of Canterbury had the right to elect archbishops, though previous monarchs had exercised considerable influence over their choice. This time it was not so simple. In 1206, the monks hurriedly (and they thought, secretly) sent their own nominee to Rome, but the chosen man blabbed, and John found out. Soon he was sending his own nomination to Rome, after securing his election by the embarrassed monks. Innocent was not impressed. In the end, he summoned more Canterbury monks to Rome and coerced those at his court to elect his choice, Stephen Langton, an Englishman who had formerly lectured at the University of Paris. Innocent consecrated Stephen in the summer of 1207, but John refused to receive him, decreeing that anyone calling Stephen "Archbishop" was guilty of high treason. For good measure, the king forced the Canterbury monks into exile.12

By March 1208, Innocent placed England under an Interdict.13 This ban (a doctrinal atom bomb) involved a suspension of religious services, rites and comforts. Non-offenders suffered alongside transgressors.14 Unflustered, John continued negotiating while administering church property and revenues through his agents. He retained the support of some clergy and a handful of bishops, and his propagandists spread the word that he was defending the ancient liberties of the English church.15 Meanwhile, John diverted church funds to assist with his overriding goal-retaking the lost lands. In November 1209, the Pope excommunicated him.16

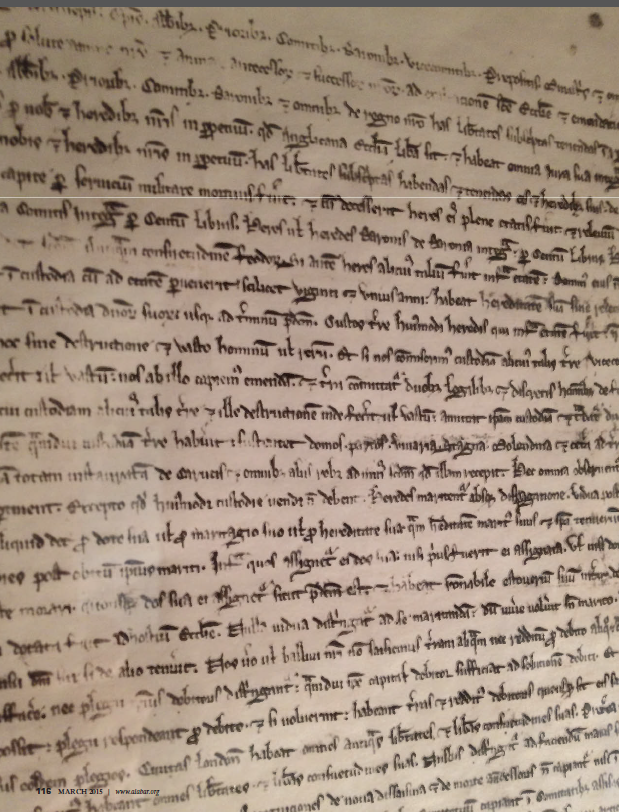

Meanwhile, the church was only one of the institutions that John was bending to his awe. The next target, which fit nicely with his family history, was the legal system. John's father, Henry II, had lifted England from the chaos of prolonged civil war17 by adroit use of his powers-most notably via the royal courts, through which he presided over the birth of a "common law" for England. Coordinated by a chief "justiciar," this judicial system included the Exchequer, where sheriffs and crown debtors came to settle accounts; the "Bench," a banc of jurists often sitting at Westminster; the court "Coram Rege," which met in the king's presence to hear pleas of the crown; and shire/county courts often presided over by traveling royal justices."18

John was interested in the law, and since he was mostly trapped in England, he paid personal attention to the courts.19 At the time-thanks to the professionalism of judges, and the reliability of writs and procedures-the royal courts were much in demand among small landowners. These litigants knew that royal courts produced definitive decisions on important matters: rights of seisin and inheritance, location of boundaries, possession of franchises.20 Thus, the king and his judges stood at the intersection of law and bureaucracy, to the benefit of many of his subjects. Wealthier litigants, to be sure, sometimes offered to pay "fines" in order to expedite a case or have it heard coram rege. Defendants sometimes offered payment to have a case against them dismissed or delayed.21

Yet John's barons, the 200 or so individuals who held lands directly from him, might as well have worn bull's-eyes.22 Not satisfied with receiving church funds on top of conventional revenues, John decided to build up his war chest by tapping into these tenants-in-chief.23 Consider John's use of the "relief," a payment owed by the heir of an estate to his lord. The amounts varied by the heir's rank-for example, 100 shillings for a knight's "fee." The customary relief for a barony was much higher (£ 100); but Glanvill, the legal authority of the day, admitted that in such matters the barons were at the king's mercy.24 John's demands for baronial relief were often "far in excess of" 100 pounds. Twice in 1210, he burdened heirs with reliefs of 10,000 marks (over £ 6,000). Three years later, he forced John De Lacy to pay 7,000 marks to inherit the "honor" (management) of Pontefract. Historian Ralph Turner observes that no one should be surprised to find these barons among the rebels of 1215.25

Barons, as well as knights and town-dwellers, were probably united in their resentment of other royal policies, too, for John, as early as 1200, had begun to force renewal of all existing charters and franchises. Each demand for payment was backed by the implicit threat that the king might sell the privilege to one of his favorites.26 Then there was "Scutage"-a contribution arbitrarily decreed by the king and paid by those who owed him military service. Henry II and Richard had imposed the Scutage 11 times from 1154 to 1199. John required it 11 times from 1199 to 1215.27 This combination-frequent assessment and harsh enforcement, plus church income-caused royal revenues to skyrocket. Turner estimates that John took in as much as £145,000 per year after 1208, almost six times the money available to Richard in 1199!28

To staff his administrative state, John preferred to employ men from the knightly class, like his pliable justice, William Briwerre, or soldiers of fortune like Falkes de Breaute, a castellan and sheriff known for his brutality.29 Such men served zealously in expectation of advancement.30 From John's standpoint, careerists were preferable to men of noble houses; the latter were more likely to be independent-minded.31 The best way to manage highborn persons, John decided, was to trap them, offering them high-priced manors, offices or wardships, knowing that if they accepted, they would fall into his hands. His Court of Exchequer, tasked with judgments regarding crown debts, was a convenient forum for humbling the arrogant, blue-blooded or otherwise. True, this court often allowed its debtors to pay in installments, and John sometimes forgave debts altogether. In other cases, however, the Exchequer forced defaulters to choose between confiscation and borrowing money at high interest from Jewish moneylenders-individuals whose persons and profits were by law completely at the king's mercy.32 In the end, incautious magnates were likely to share the fate of cash-strapped heirs. Most ended up as the king's debtors.33

That was the way John liked it, but sometimes his paranoia overrode his sense of reality. In 1201, John forgave a debt owed by the father of his close supporter...

To continue reading

Request your trial