The Changing Landscape for Securities: Fraud Claims Under Georgia Law

| Citation | Vol. 17 No. 1 Pg. 0026 |

| Pages | 0026 |

| Publication year | 2011 |

A Look at the Law

by Brett "Ben" Rogers and Leah A. Epstein

When making decisions about purchasing or selling securities, few investors are in a position to "kick the tires" of the relevant company. Instead, they receive information provided by the issuers of the securities or by other market participants. Multiple federal and state laws regulate the accuracy of that information. Thus, when an issuer of securities provides false or misleading information to investors and the market, or when the issuer fails to disclose pertinent information despite an obligation to do so, investors have multiple bases for bringing suit.

For example, investors may sue under the federal securities laws, including an implied right of action under Federal Rule 10b-5 (Rule 10b-5),[1] and an express right of action under Section 12 of the Securities Act of 1933 (Section 12).[

2

] In addition, investors may pursue state-law tort claims sounding in fraud or negligent misrepresentation. Finally investors have the option of suing under the antifraud provisions of state "blue sky laws," which regulate securities offerings at the state level.Over the past couple of years, Georgia's securities laws have undergone a number of changes that will impact litigants bringing securities claims, either under the Georgia securities statute or the common law. Among these are changes engendered by the General Assembly's enactment of the Georgia Uniform Securities Act of 2008 (the 2008 Act),[3] which replaced Georgia's prior securities statute, the Georgia Securities Act of 1973 (the 1973 Act). The new and relatively untested provision of the 2008 Act governing private claims for misrepresentations or omissions in connection with the sale of securities includes several departures from prior law. Some of these departures may ease a plaintiff’s burdens of pleading and proof, while others may substantially narrow the scope of the private right of action to enforce the 2008 Act’s anti-fraud provisions. In addition, on Feb. 8, 2010, the Supreme Court of Georgia issued its unanimous opinion in Holmes v. Grubman,[4] which included a discussion of loss causation that could have far-reaching implications for litigants bringing securities cases in Georgia.

The Georgia Uniform Securities Act of 2008

On July 1, 2009, the 2008 Act went into effect, replacing the 1973 Act.[5] The 2008 Act brought with it several substantive changes affecting civil claims for misrepresentations or omissions in connection with the sale of a security. Most significantly, the new statute altered the landscape for private rights of action from that which existed under the prior statute. Although the 1973 Act created a private right of action to enforce a claim based on Federal Rule 10b-5, the 2008 Act contains instead a private right of action to enforce a claim that is based on Section 12 of the Securities Act of 1933. The 2008 Act also includes a provision modeled on Rule 10b-5, but it does not appear to provide a right for private litigants to enforce that provision. This shift away from the Rule 10b-5 model has important implications for the Georgia securities bar.

Switch from Rule 10b-5 Model to Section 12 Model

The 1973 Act was based on the Uniform Securities Act of 1956. The 1956 Uniform Act included both a provision modeled on Rule 10b-5[6] and a provision modeled on Section 12(2) of the Securities Act of 1933.[7] The 1956 Uniform Act only included a private right of action to enforce the latter provision.[8] In adopting its version of the Uniform Securities Act of 1956 in the 1973 Act, however, the Georgia General Assembly included an altogether different private right of action. Specifically, the 1973 Act included a provision creating an express private right of action to enforce its Rule 10b-5 analog in place of the 1956 Uniform Act’s private right of action modeled on Section 12(2)[9]

Thirty-five years later, the General Assembly changed course, enacting in the 2008 Act a statute that hews more closely to the current version of the uniform securities statute, the Uniform Securities Act of 2002.[10] That is, in adopting the 2008 Act, the General Assembly included a private right of action that is more akin to Section 12 of the 1933 Act than to Rule 10b-5.[11] That private right of action is provided for in O.C.G.A. § 10-5-58. Unlike its predecessor in the 1973 Act, the Rule 10b-5 analog in the 2008 Act—O.C.G.A. § 10-5-50—does not include a private right of action.[12] This lack of a private right of action is confirmed by the official comments to the uniform act provision on which O.C.G.A. § 10-5-50 is based, Section 501 of the Uniform Securities Act of 2002,[

13

] which state that "[t]here is no private cause of action, express or implied, under Section 501."[14

] The official comments go on to state that Section 509 of the 2002 Uniform Act—which is the section of the 2002 Uniform Act that creates the private right of action on which O.C.G.A. § 10-5-58 is based—"expressly provides that only Section 509 provides a private cause of action for conduct that could violate Section 501."[15

] Because Section 509 of the 2002 Uniform Act is modeled on Federal Section 12, it appears that the General Assembly has eliminated the right of civil litigants to directly enforce the anti-fraud provisions of the 2008 Act that are derived from Federal Rule 10b-5.Implications of Change to the Section 12 Model

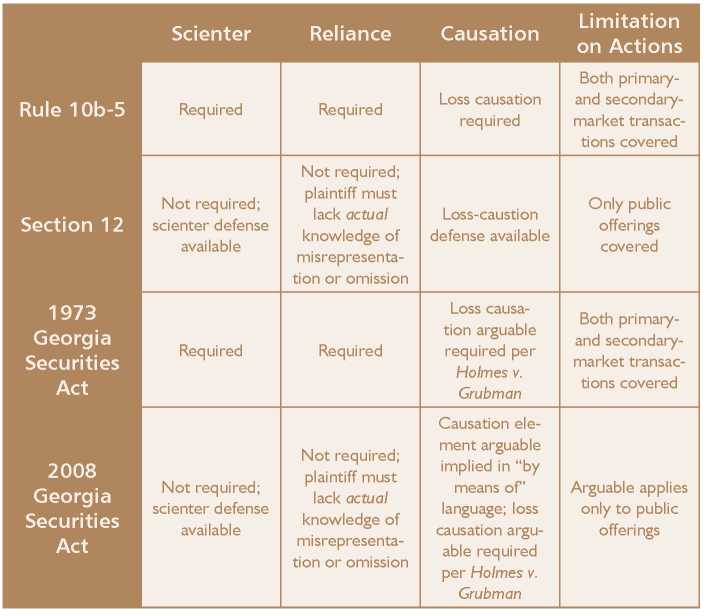

The significance of the differences between the 1973 Act's private right of action for securities fraud and the private right of action contemplated in the 2008 Act can be appreciated, in part, by examining the differences between Federal Rule 10b-5 and Section 12. Although Rule 10b-5 and Section 12 both create civil liability for misrepresentations and omissions in connection with sales of securities, the two provisions require different elements of proof, have different standing requirements and include different defenses.

Elements of a Claim

To bring an implied right of action under Federal Rule 10b-5, plaintiffs must establish the following elements: (1) a "material misrepresentation (or omission)" made in "connection with the purchase or sale of a security"; (2) scienter; (3) materiality; (4) reliance; and (5) loss causation.[

16

] The requirement that the alleged misrepresentation or omission be made "in connection with the purchase or sale of a security" has been interpreted to be a standing requirement such that a private litigant cannot bring suit under Rule 10b-5 unless he has purchased or sold the relevant security.[17

] Under the 1973 Act, the Georgia courts largely followed the federal courts in identifying the elements of a securities-fraud claim.[18

]

In contrast, a securities-fraud claim brought under the version of Section 12 on which the private right of action in the Uniform Securities Act of 1956 was based required proof of neither scienter, reliance nor loss causation.[

19

] Likewise, the Official Comments to Section 509 of the Uniform Securities Act of 2002, on which the private right of action in the 2008 Act is based, acknowledge that the private right of action for securities fraud in the Uniform Securities Act of 1956 did not require proof of either causation or reliance.[20

]The original Section 12 did provide a defense to sellers who were able to establish that they did not know, and in the exercise of reasonable care could not have known, of the alleged untruth or omission.[21] As discussed infra, the 2008 Act also creates this defense. Thus, the defendant's scienter is relevant under these statutes, even if not part of a plaintiff's prima facie case.

Accordingly, some may argue that, as under the Uniform Securities Act of 1956, a plaintiff bringing suit under the O.C.G.A. § 10-5-58 of the 2008 Act need not plead either the defendant's scienter or causation. O.C.G.A. § 10-5-58 expressly requires proof that: (1) the defendant sold a security, (2) "by means of an untrue statement of a material fact or an omission to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statement made, in light of the circumstances under which it is made, not misleading," and (3) the purchaser did not know of the untruth or omission.[22] Thus, some will no doubt argue that the only scienter a plaintiff must establish as part of his prima facie case is his own lack of knowledge. Moreover, a plaintiff suing under O.C.G.A. § 10-5-58 may argue that he is entitled to bring suit even if his lack of knowledge resulted from his own negligence.

On the other hand, it is possible to read a causation element into the 2008 Act's requirement that the security has been sold "by means of" a material misstatement or omission. That is, a court could determine that a security was sold "by means of" a misstatement or omission only where the misstatement or omission caused the transaction to be consummated. Georgia courts are not obliged to follow federal law or the official comments to the uniform statute in this regard. Interpreting the "by means of" language in the 2008 Act to require proof of causation would make the statute more consistent with current federal law, as Congress has added a loss-causation defense to claims brought under Section 12.[23] Thus, although neither Section 509 of the 2002 Uniform Securities Act nor O.C.G.A. § 10-5-58(b) of the 2008 Act includes an explicit loss-causation defense, the 2008 Act's drafters may have omitted such a defense from O.C.G.A. § 10-5-58 in the belief that the statute's "by means of" language implicitly imposes the burden of pleading and proving loss causation on the plaintiff. Notably, the Supreme Court of Georgia gave some indication in Holmes — after the 2008 Act had been enacted— that loss causation may be required to bring a...

To continue reading

Request your trial