In Defense of Voir Dire

| Citation | Vol. 17 No. 1 Pg. 0014 |

| Pages | 0014 |

| Publication year | 2011 |

A Look at the Law

by Michael L. Neff

A Brief History of Voir Dire

Voir Dire: Ancient Foundations and Early Developments

Our legal system requires that we review legal history and consistently apply legal principles. When we look back at the history of the jury, we find that the jury as a means of resolving disputes is as old as civilization itself.[1] Juries in some form were utilized in Ancient Egypt, Mycenae, Druid England, Greece, Rome, Viking Scandinavia, the Holy Roman Empire and even Saracen Jerusalem before the Crusades.[2] The "contemporary" notion of the jury dates back as early as 500 B.C.E.[3] in Athens, Greece. The Athenian juries — called "dikasteria—were extremely large, ranging from 200 to 1500 members.[4]

The American emphasis on voir dire relates back to 12th century England.[5] In 1166, Henry II proclaimed the Assize of Clarendon, which forced civil litigants to present their evidence to laymen.[6] In these early stages of common law, the king selected jurors based on their personal knowledge of the facts and issues in the case.[7] In fact, jurors were required to serve not only as fact finders, but as investigators and researchers as well.[8]

As a result of an individual juror's power, it became commonplace for jurors to be challenged for bias before being allowed to hear a case.[9] Challenging jurors became vitally important as rules of evidence and procedure became a routine part of a civil trial.[10]

The paradigm shifted away from jurors needing personal knowledge to jurors solely being finders of fact.[11] Impartiality became paramount. By the end of the 15th century, the notion that jurors had to be impartial was firmly entrenched in the English common law.[12] In determining which jurors were unbiased, the English common law wrestled with the issues of preemptory challenges and challenges for cause, recognizing that both may be necessary in order to ensure a fair trial.[13] Thus, the need to remove jurors based on bias has been recognized and pursued for more than 600 years.

Voir Dire: A Distinctly American Tradition

As America was on the precipice of independence, England enacted the Massachusetts Jury Selection Law of 1760, which prohibited the questioning of jurors once the sheriff had chosen them for duty.[14] The inability of parties to verify the impartiality of jurors enraged citizens and served as but one of many justifications for independence.

Thomas Jefferson is one of the founding fathers who recognized the importance of an impartial jury.[15] In writing to his friend, Colonel William Stephen Smith, he proclaimed, "[I]t astonishes me to find . . . that [our countrymen] should be contented to live under a system which leaves to their governors the power of taking from them the trial by jury in civil cases. . . . "[16] He later opined, "I consider trial by jury as the only anchor ever yet imagined by man, by which a government can be held to the principles of its constitution."[17]

Thus, it is no surprise that the Declaration of Independence was justified by King George III "depriv[ing] us, in many Cases, of the Benefits of Trial by Jury." Further, the Sixth and Seventh Amendments to the U.S. Constitution specifically address the fairness of the jury trial.[18] An impartial trier of fact, allowing for "free, fearless and disinterested" analysis of the evidence is the most important right in our system of justice.[19]

By the time the sun had set on the Revolution, voir dire had become a cornerstone of American jurisprudence. Legal historians recognize Chief Justice John Marshall's persuasive ruling while sitting as trial judge in the Aaron Burr treason trial that cemented the right of parties to question jurors about their preconceptions about a case.[20] Justice Marshall recognized that an impartial jury was "required by the common law and secured by the Constitution."[21]

Jefferson's and Justice Marshall's vision on voir dire are bedrocks of our judicial system. The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized the importance of voir dire. Every party is entitled to "present his case with assurance that the arbiter is not predisposed to find against him."[22] By "preserv[ing] both the appearance and reality of fairness," this "requirement of neutrality" by judges and juries fosters "the feeling, so important to a popular government, that justice has been done."[23]

The U.S. Supreme Court has recognized that such fundamental fairness requires not just "an absence of actual bias" from judges and juries but also endeavors to "prevent even the probability of unfairness."[24] Of course, one of the most important "mechanism[s] for ensuring impartiality is voir dire, which enables the parties to probe potential jurors for prejudice."[25] Voir dire is the quintessential tool for protecting an individual's right to an impartial jury.[26]

Voir Dire: A Strong Tradition in Georgia

Georgia courts recognize and emphasize the importance of voir dire. The Supreme Court of Georgia has held that "an impartial jury is the cornerstone of the fairness of trial by jury"[27] and that "a jury trial is a travesty unless the jurors are impartial."[28] Further, the Court has explained, "[j]ury selection is a vital and extremely important part of the trial process and should be treated as such by all concerned."[29] Thus, because the fate of the litigating parties rests in the hands of the jury, "the primary way to arrive at the selection of a fair and impartial jury is through voir dire questioning."[30]

The Court's concern for the fundamental fairness of a trial has led it to limit practices such as juror rehabilitation, which threaten the integrity and fairness of the jury system. In Kim v. Walls, the Supreme Court of Georgia crafted a ruling that endorsed counsel having the "broadest of latitude" in questioning jurors who have any relationship with a party.[31] The Court held that "rehabilitating" questions by the trial court that impermissibly curtailed the requisite inquiry by counsel into a juror's bias were improper.[32] Previously, in the same case, the Court of Appeals had articulated the same policy regarding voir dire, explaining:

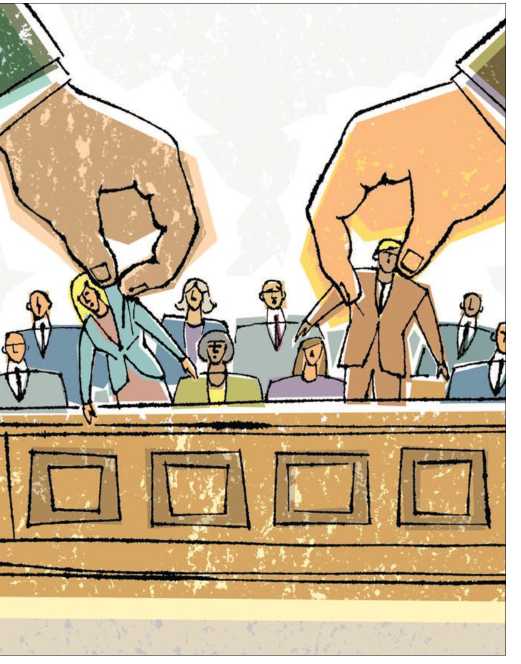

A trial judge should err on the side of caution by dismissing, rather than trying to rehabilitate, biased jurors because, in reality, the judge is the only person in a courtroom whose primary concern, indeed primary duty, is to ensure the selection of a fair and impartial jury. While the parties to litigation operate under the guise of selecting an impartial jury, the truth is that having a jury which is truly fair and impartial is not their primary desire. Instead, their goal is to select a jury which, because of background or experience or whatever other reason, is inclined to favor their particular side of the case. The trial judge, in seeking to balance the parties' competing interests, must be guided not only by the need for an impartial jury, but also by the principle that no party to any case has a right to have any particular person on their jury.[33]

In affirming the decision of the Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court stated:

Running through the entire fabric of our Georgia decisions is a thread which plainly indicates that the broad general principle intended to be applied in every case is that each juror shall be so free from either prejudice or bias as to guarantee the inviolability of an impartial trial . . . . [I]f error is to be committed, let it be in favor of the absolute impartiality and purity of the jurors.[34]

Today, several basic principles govern the decision of a motion to strike a prospective juror for cause: (i) neither party has any right to any juror; (ii) jurors must be free from even a suspicion of prejudgment as to any issue, bias, partiality or outside inferences; (iii) the Court decides whether there is any basis to suspect possible prejudice; and (iv) trial courts are instructed to err on the side of caution and to strike a prospective juror if any doubt exists.

The Standard for Voir Dire in Georgia

Fundamentals of Jury Selection in Georgia

According to the plain meaning of the Georgia Code, "jury selection" only begins after voir dire reveals those prospective jurors which should be excused as a matter of law or as a matter of fact. Challenges based on principal grounds require the removal of a juror as a matter of law. Challenges based upon favor are factually based challenges and are discretionary with the trial court.

Once biased jurors have been excused, a full panel of either 12 or 24 impartial jurors should be left for "jury selection."[35] The regular panel of prospective jurors must ultimately consist of a "full panel of . . . competent and impartial jurors from which to select a jury."[36]

Under Georgia law, it is possible for so many prospective jurors from the original panel to be dismissed that the remaining panel is not full, requiring additional competent and impartial jurors to be added before requiring the parties or their counsel to strike a jury.[37] Thus, parties are not required to exhaust their precious peremptory strikes on unqualified jurors.[38]

Challenges for Cause

Whenever a suspicion regarding a prospective juror's ability to be impartial arises, a challenge for cause should be interposed. Unlike peremptory challenges, a challenge for cause must be based upon a specified reason. The stated reason will cause the challenge to fall into one of two categories: (1) those based upon principal grounds or (2) those based upon favor.

Challenges for principal cause are based on facts which, if proven, automatically disqualify the juror from serving.[39] Challenges for favor require a reasonable suspicion that the juror is biased, based either on 1) admissions of the juror or...

To continue reading

Request your trial