From Blueprints to Megabytes: Copyright Issues for Architects, Contractors and Developers in the Digital Age

| Publication year | 2008 |

| Pages | 0022 |

by Andrew Crain and Melissa Rhoden

Like many professions today, the architectural design process, including that for high-rise residential condominiums, has changed considerably in recent years. Today's architects have, in large part, exchanged their pencils, rulers and drawing tables for computers and computer-aided drafting (CAD) software programs and computer desks. The benefits of these changes are substantial (although likely debatable by some old-school architects), as architectural designs created by CAD programs can be easily changed, viewed, printed and saved for future use.

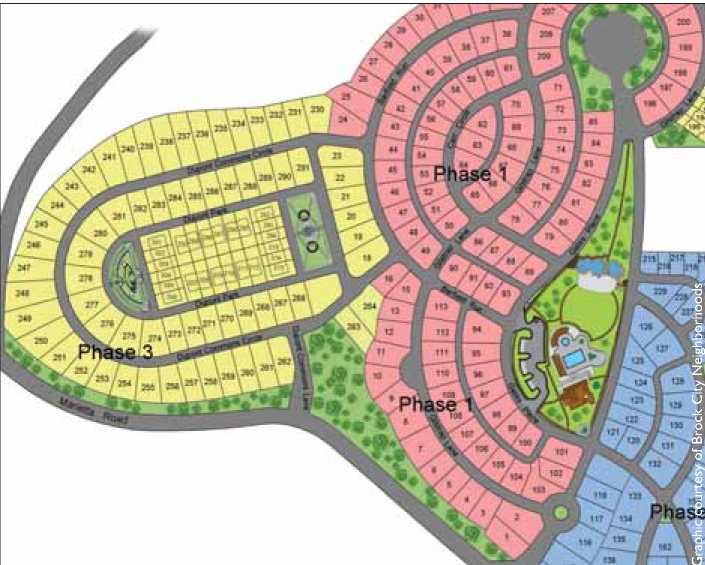

Electronic architectural design is not without its own risks and challenges. Electronic architectural drawing files, like any digital document, can be transferred virtually anywhere almost immediately. Thus, for any number of reasons, the architectural drawing files of one architect or firm may end up on the desk, or worse, the computer screen, of another architect or firm. Although there certainly may be legitimate and appropriate reasons for this to occur, problems can arise when the content from architectural drawing files finds its way into architectural drawing files of another architect on a different project. When this happens, significant copyright infringement liability can result, not only for the individual architect who made the unauthorized copy, but also for the architectural firm whose drawings contain the copied material. Potentially, the developer of the project, contractors and the end users (i.e., tenants) of the completed building can be involved.

When a subsequent project is designed by an architect who did not create the initial design, these issues can be particularly troublesome for developers attempting to create a series of building projects with common designs and features. If the developer fails to obtain approval from the initial architect, any unauthorized re-use of that architect's drawings, provided that they have been copyrighted, can present substantial problems for all involved in subsequent projects.

If the entertainment industry has taught us any copyright lessons, it is that digital computer files are not immune to copyright laws. Thus, architects, developers and contractors, all of whom increasingly rely on architectural drawing files that are digitally created and maintained, should be aware of potential

copyright issues associated with these media.

How Does Copyright Law Apply to Architecture?

For all copyrightable works, including works related to architecture, copyright protection exists in an original work of authorship as soon as the work is created, i.e., fixed in a tangible medium of expression.[1] Although there is no requirement that one must register an original work to obtain a protectable interest, in order to initiate an action for infringement, an application for copyright registration must first be filed with the U.S. Copyright Office.[2] The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit has held that the issuance of the certificate of registration is required prior to filing a lawsuit for infringement.[3] Notwithstanding this registration requirement, perhaps the threshold question is what is copyrightable when it comes to architecture.

Before the enactment of the Architectural Works Copyright Protection Act (AWCPA) in 1990,[4]works of architecture were afforded only limited copyright protection. Architectural plans could be registered for copyright as a "pictorial, graphic, and sculptural work" under 17 U.S.C. § 102(a)(5), but the actual architectural structures were allowed almost no protection.[5]As its legislative history indicates, prior to the enactment of AWCPA, it was possible to construct an identical building from architectural plans or drawings, and escape copyright liability, provided that the plans or drawings themselves were not actually copied.[6]Congress enacted the AWCPA specifically to extend protection to "architectural works" as a new category of authorship.

Thus, an architectural work is the "design of a building as embodied in any tangible medium of expression," which may include "a building, architectural plans, or drawings."[7] Moreover, an architectural work includes the overall form of a building as well as the "arrangement and composition of spaces and elements in the design."[8] A copyright for architectural works explicitly excludes, however, individual standard features, such as doors and windows.[9]This exclusion makes sense because of the functionality exclusion of copyright, i.e., copyright protects expression and not function or utility.

That does not mean that the composition or arrangement of those features is not copyrightable, as the 11th Circuit recently found in Oravec v. Sunny Isles Luxury Ventures, L.C.[10] This point is also reflected in the legislative history of the AWCPA, which recognizes that creativity in architecture frequently takes the form of a selection, coordination or arrangement of unprotectable elements into an original, protectable whole.[11]

The primary effect of the AWCPA is to provide copyright protection to physical architectural works. The AWCPA does not apply to copyrights in technical drawings. Before 1990, only architectural plans were protected by copyright, and only against copying as technical drawings, not as embodied in a structure based on the drawings. The 1990 Act did not change this law. Rather, the 1990 Act added protection in § 102(a)(8) of the copyright statute for the built structure, which was a new form of protection with its own registration requirements and infringement analysis.[12]

Now, a work can obtain protection as both an architectural work (under § 102(a)(8)) and a technical drawing (under § 102(a)(5)), but only if the work is registered under both categories. This requires two separate copyright registration certificates. These steps, in conjunction with the placement of the proper notice of copyright, should afford the strongest level of protection, and therefore provide the most options with regard to remedies, should infringement occur.

Proving Copyright Infringement

In order to establish a prima facie case of copyright infringement for any copyrighted work, including architectural technical drawings and works, a copyright owner must prove that: (1) he or she owns a valid copyright...

To continue reading

Request your trial