The Medical Monitoring Tort Remedy: Its Nationwide Status, Rationale, and Practical Application (a Possible Dynamic Tort Remedy for Long-term Tort Maladies)

| Publication year | 2023 |

[Page 109]

Edgar C. Gentle III *

Abstract: The author administers six mass tort settlements with a medical component, including two with medical monitoring. This article reviews the status and history of medical monitoring, known claimant medical monitoring participation rates, the rationale for the remedy, arguments for and against its implementation, and its execution in practice. The author suggests a more holistic medical monitoring remedy, which includes not only testing/or disease but paying claimants for personal injury when they get sicker later, from a capped fund and under an agreed payment matrix, to provide closure to defendants and class members for claims resulting from toxic substances and product defects, which have long-term and often unknown effects on plaintiffs. It is suggested that this remedy is the logical long-term result of the evolution of medical monitoring, and will provide a much needed dynamic remedy for long-term maladies.

Introduction

The medical monitoring remedy is an evolving tort with differing levels of acceptance in the states, being law in 14 states and being rejected so far by 23 states. Eleven states have not addressed the issue and two states have divided decisions.

[Page 110]

In a nutshell, medical monitoring has been implemented where a population has been exposed to a toxin or defective product, but not all exposed persons manifest personal injury. States implementing medical monitoring require the defendant to provide testing of the population over time to see if the personal injury occurs, and states rejecting medical monitoring do so based on the argument that, without personal injury, there is no tort claim.

In this society, toxic substances are released and medical products are used without knowing fully their long-term effects. It is therefore suggested that, instead of applying the classic tort barrier to recovery based on lack of personal injury, courts should embrace the need to have a current remedy for unknown long-term effects of exposure to toxic substances or dangerous products with both a testing and a payment component, in order to provide the plaintiff with a long-term remedy, allow the defendant closure on its legal exposure, and to circumvent the statute of limitations problem that will be encountered if such a holistic remedy is not implemented, if a plaintiff must first be injured to file a claim.

Currently, this suggested long-term remedy has not been implemented. It is suggested, however, that without developing medical monitoring to this logical policy conclusion, it will remain a hollow remedy: What good is it to know that you are injured if you are not compensated?

The Rationale and Beginnings of Medical Monitoring and a Geographic Survey

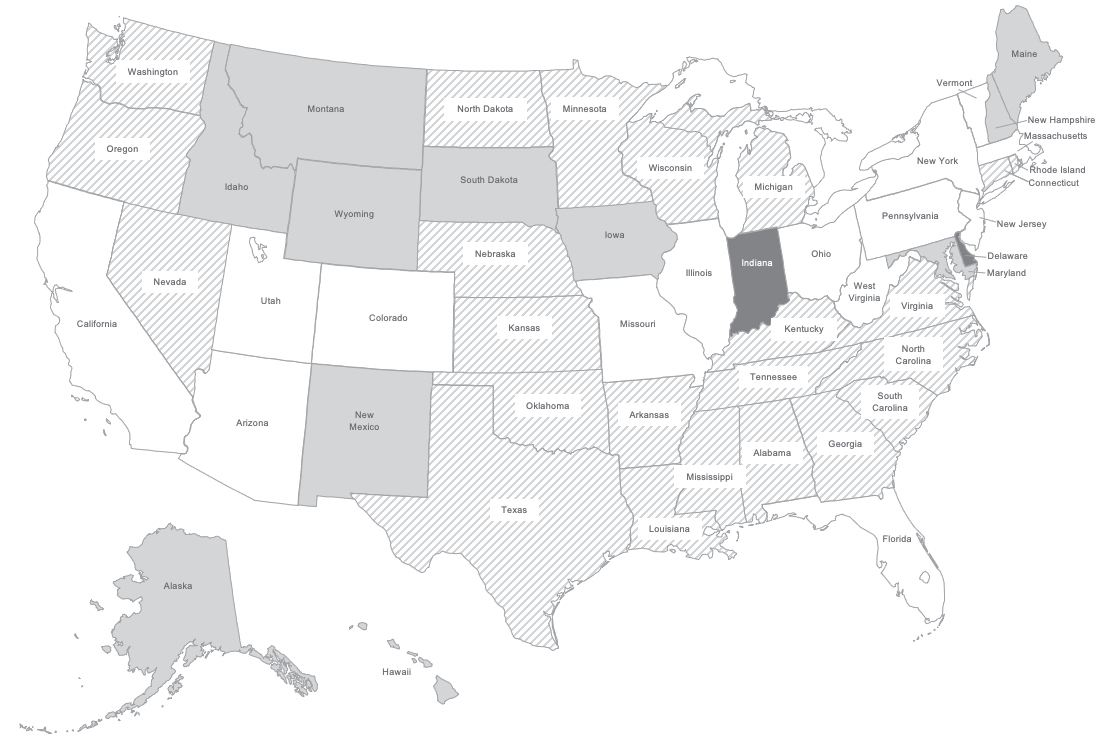

Looking at the map in Figure 1, the 14 states allowing medical monitoring do not follow a clear political pattern. We have California, thought to be a blue state. But Arizona and Utah honor the tort, as well as Missouri. Florida is thought to be politically divided, but it is in the medical monitoring bracket.

There are at least three useful 50-state surveys of medical monitoring. 1

To show how medical monitoring keeps evolving, the BP oil spill disaster, much as the Friends for All Children case described below involving Vietnamese children, provided such a compelling set of facts that Judge Barbier allowed a medical benefits class

[Page 111]

Figure 1. Medical Monitoring Law Map

Legend

■ White = 14 states that allow medical monitoring without physical injury: Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Utah, Vermont, and West Virginia.

■ Striped = 23 states that do not allow medical monitoring without physical injury: Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin.

■ Dark gray = 2 states in which the laws are divided: Delaware and Indiana.

■ Light gray = 11 States in which the issue has not been addressed: Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, and South Dakota.

action settlement, applicable to claimants not only in Florida, where medical monitoring has been approved, but in Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi, where it is has not. 2

So, the law may continue to evolve to meet society's needs in this field.

Simply put, states that allow medical monitoring do so when a group of claimants has been exposed to a known hazardous substance, such as lead, or a dangerous product, such as football

[Page 112]

helmet concussions, or air decompression in an airplane, through the conduct of the defendant, with the claimants therefore being at increased risk of contracting disease. Under this tort remedy, claimants are tested periodically, for an agreed or decided period, usually between 10 and 40 years, to see if they contract the disease linked to the toxic substance or dangerous product.

Thus, medical monitoring recognizes the long-term harmful nature of toxins and man-made products, thereby matching a remedy with the malady.

The tort is 30 years old. Medical monitoring, like many torts, got its start with a sympathetic set of facts, in Friends for All Children Inc. v. Lockheed Aircraft Corp. 3 In Friends for All Children, the court evoked public policy to create a remedy for 149 Vietnamese orphans who were injured in an aviation accident in Vietnam.

Most know the case: a plane loaded with Vietnamese orphans to be adopted in America crashed, resulting in cabin decompression and neurological disorders, known as minimal brain dysfunction (MBD), in the children. Lockheed argued that tort law in the District of Columbia did not recognize a cause of action for diagnostic exams. The court ignored Lockheed's argument and established a half million dollar fund to conduct long-term brain exams of the children to determine if they were hurt.

The District of Columbia Circuit Court upheld the District Court's decision, with the following two quotations being frequently cited to justify the tort:

Jones is knocked down by a motorbike when Smith is riding through a red light. Jones lands on his head with some force. Understandably shaken, Jones enters a hospital where doctors recommend that he undergo a battery of tests to determine whether he has suffered any internal head injuries. The tests prove negative, but Jones sues Smith solely for what turns out to be substantial costs of the diagnostic examinations. 4

It is difficult to dispute that an individual has an interest in avoiding expensive diagnostic examinations just as he or she has an interest in avoiding physical injury. When a defendant negligently invades this interest, the injury

[Page 113]

to which is neither speculative nor resistant to proof, it is elementary that the defendant should make the plaintiff whole by paying for the examinations. 5

The second most famous medical monitoring case is Ayers v. Jackson Township, 6 a classic community toxic tort medical monitoring case. Here, a township in New Jersey contaminated water with toxic pollutants reaching into an aquifer from the township landfill. In finding that the residents were entitled to the cost of medical surveillance based on enhanced risk of disease as a result of exposure to the toxic chemicals, the New Jersey Supreme Court held:

That the cost of medical surveillance is a compensable item of damages where the proofs demonstrate, through reliable expert testimony predicated upon the significance and extent of exposure to chemicals, the toxicity of the chemicals, the seriousness of the diseases for which individuals are at risk, the relative increase in the chance of onset of disease in those exposed, and the value of early diagnosis, that such surveillance to monitor the effect of exposure to toxic chemicals is reasonable and necessary. The medical surveillance claim seeks reimbursement for the specific dollar costs of periodic examinations that are medically necessary notwithstanding the fact that the extent of plaintiffs' impaired health is unquantified.

We find that the proofs in this case were sufficient to support the trial court's decision to submit the medical surveillance issue to the jury, and were sufficient to support the jury's verdict. 7

In noting that medical monitoring usually does not adjudicate personal injury claims and allows the medical monitoring claimants to reserve them for the future, the New Jersey Court blessed the "discovery" rule for toxic tort-related statutes of limitation. 8 This construction of the relevant statute of limitations works hand-in-glove with medical monitoring, allowing a claimant who discovers that he or she is sicker later still to file a claim for personal injury in the courts.

The evolution of this tort is not different from the creation of negligence law during the industrial revolution in England. 9 Prior to

[Page 114]

the industrial revolution, English tort law was limited to intentional harm. However, as people began to live closer together, factories were created and modes of transportation became increasingly dangerous, and a duty of care in negligence was invented to adjust the law of torts to factual reality.

Arguably, the same is occurring or should occur with medical monitoring. We, as lawyers, devote much of our practice to latent injuries in our current society, from toxic chemicals, pharmaceutical drugs, and other human-created substances or products. Thus, tort law may need to accommodate these changes if it is to continue to maintain its role of adjudicating disputes resulting in injury or potential injury.

So, this article is a mere snapshot. Fifty years from now there may be ubiquitous medical monitoring with the holistic approach suggested in this article, or no medical monitoring at all.

An...

To continue reading

Request your trial