The Power of Words

| Jurisdiction | South Carolina,United States |

| Citation | Vol. 33 No. 1 Pg. 40 |

| Pages | 40 |

| Publication year | 2021 |

The South Carolina Black Code and Citizen's Arrest in South Carolina

By Kathleen Warthen and Roger M. Stevens

When one of our clients was arrested at gunpoint by several citizens with no evident authority, we began researching our state's citizen's arrest statutes. And, we were intrigued by T. Jarrett Bouchette's article in this magazine's January 2021 edition and submit this article to offer an expanded viewpoint regarding the points raised in that article.[1] In particular, we think it is important to explore the history of racial animus underpinning these statutes as they exist today, particularly as the legislature considered multiple bills this session to repeal or amend the statutes in the wake of Ahmaud Arbery's death and increased awareness of the legacy of slavery.[2]

The episode in question started rather simply: our client, a Black male, left a club on private property to return to his car across the street. Preparing for a hunting trip, he moved several firearms around in his truck, in view of the club's security guards. The security guards crossed the street, arrested our client at gunpoint, and conducted a search of his vehicle. S.C. Code Section 40-18-110 would have arguably granted this authority to the security guards had they arrested our client on private property, but they did not do so.[3]The arrest took place away from the private property the security guards were protecting. This made what took place very similar to situations where municipal police officers leave their jurisdictions and make arrests in a jurisdiction where they do not have law enforcement power. Unless the municipal police officers are operating outside their jurisdiction with specific statutory authorization or under a valid multi-jurisdictional agreement, the officers can only make warrantless arrests as private citizens pursuant to South Carolina's Citizen's Arrest Laws, S.C. Code Sections17-13-10 and 17-13-20.[4] In representing our client, we considered the origins and original purpose of S.C. Code Sections 17-13-10 and 17-13-20.

Statutory origin of South Carolina's Citizen's Arrest Laws

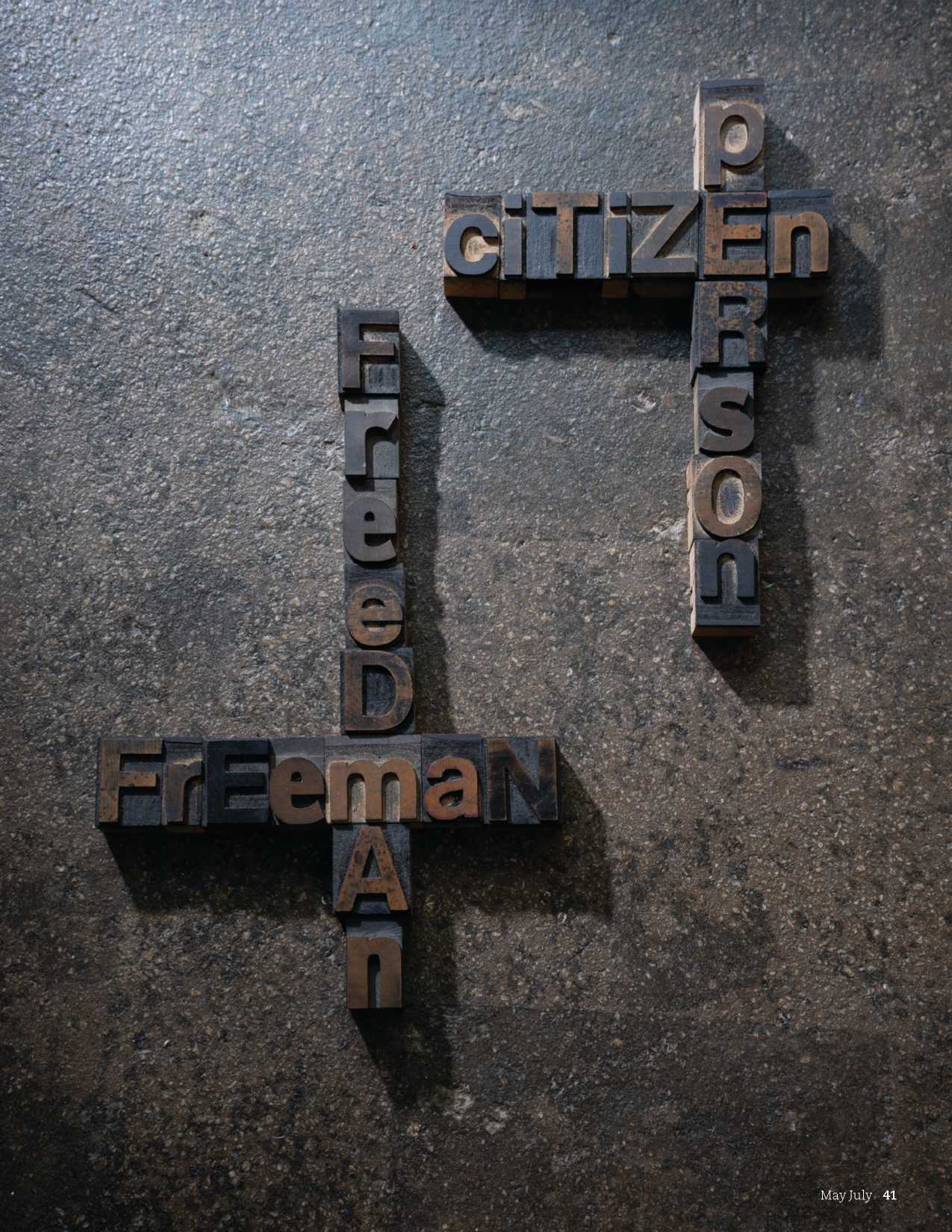

Statutory interpretation has long been divided into two distinct camps: textualism and purposivism. Purposivists typically argue that the legislative body in question passed a statute to achieve g an objective, and judges should "enforce the spirit rather than m the letter of the law when the two conflict."[5] On the other hand, textualists adhere to the belief that judges have a duty "to give effect to the duly enacted text (when clear), and not unenacted evidence of legislative purpose."[6] Regardless of your camp, the meaning of individual words matter and are powerful factors when reading statutes.

The South Carolina Citizen's Arrest Laws are excellent examples of statutes where the meaning of individual words matter. Sections 1713-10 and 17-13-20 were originally written as part of the Black Code, which was a series of laws passed by the South Carolina Legislature in late 1865, immediately after the Civil War. In examining these sections, first, it is important to meet the individuals who proposed these laws and to briefly examine the history that led to their development.

Antebellum South Carolina relied heavily on slavery for its agrarian-focused society and used a hybrid law enforcement model to control its slave population.[7] This hybrid model consisted of local law enforcement, state militia and slave patrols, known simply as "patrols."[8] Slave patrols played a key role in preventing slave uprisings and also hunted down and returned fugitive slaves to their owners.[9] As the Civil War ended, near lawless conditions began to spread throughout South Carolina, and vigilante groups, some of which were composed of former slave patrols, began to fill the void. In response, the U.S. Army stepped in and implemented martial law. Simultaneously, the South Carolina Legislature responded by implementing tough control methods for the newly freed Black population, which included a vetoed attempt to restore slave patrols and the package of laws that would become known as the Black Code.[10]

The Black Code was specifically designed by pre-eminent South Carolina jurists, Judge David Wardlaw and Armistead Burt, with the intent to maintain nearly the same level of control over the Black population as before the Civil War. The Provisional Governor of South Carolina hand selected Judge Wardlaw and Mr. Burt to write a report containing suggested statutes "relat[ing] to the government and protection of persons of color."[11] Wardlaw served as a "superior court judge," and Burt was "widely acknowledged as ... [one] of the most respected and eminent constitutional lawyers of the South."[12] As lawyers, Wardlaw and Burt were experienced advocates, served as elected members of the South Carolina Legislature at various points in their careers, and in Burt's case, also served as an elected member of the U.S. House of Representatives.[13] Wardlaw also served as Speaker of the South Carolina House of Representatives.[14]Wardlaw and Burt certainly knew that the words used during statutory construction were of profound importance.

The South Carolina Black Code, as first proposed by Wardlaw and Burt in October 1865, defined a person of color as "[a]ll free negroes, mulattoes and mestizoes, all freedmen and freed women, and all descendants, through either sex, of any of these persons."[15] The term "freedmen" deserves particular attention, as this term applies almost exclusively to "emancipated slave[s]."[16] A "freedman" is not a "freeman." A freeman is "entitled to full political and civil rights" and "is not a slave."[17] Burt was known to use the term "freemen," and used it to particular effect a few years after he helped write the South Carolina Black Code.

In August 1868, Burt was elected president of the South Carolina Democratic State Convention. During his closing speech of the Convention, Burt addressed the crowd: "We may yet live as freemen in the possession of the soil upon which we were born - of this country which was discovered by the white man, settled by the white man, made illustrious by the white man, and must continue to be the white man's country. [Applause.]"[18]The term "freemen" has special significance in Burt's speech. There is no doubt as to exactly who Burt was referring to in his 1868 speech - the white man.

The distinction between "freedmen" and "freemen" is important because Wardlaw and Burt had no intention of treating them equally. "Freedmen" were former slaves, and "freemen" were their former owners. The Black Code was clear about what rights "persons of color" and "freedmen" would have in post-Civil War South Carolina.[19] "Persons of color" were "not entitled to social or political equality with white persons" and Wardlaw and Burt ensured that the proposed...

To continue reading

Request your trial