Restorative Justice Solutions for Mass Incarceration

| Publication year | 2018 |

| Author | Jennifer Lim* |

Jennifer Lim*

Mass incarceration in the U.S. today is a reality with global dimensions. With less than 5% of the world's population, the U.S. houses 25% of the world's known incarcerated population. In 2002, the United Nations Economic and Social Council adopted a resolution calling on member nations to draw upon the guidance of restorative justice programs and processes developed by a core group of experts, for the development of criminal justice reform. Since then, an increasing number of states in the U.S. have passed legislation that incorporates restorative justice as part of their criminal justice statutes, with some states merely approving the use of restorative justice and others actively promoting the implementation of restorative justice processes within their departments of corrections. This article discusses the problem of mass incarceration and highlights the need for an alternative approach to dealing with crime and deviance. Restorative justice is emerging as an increasingly viable approach for criminal justice systems around the world, as illustrated by examples in China and New Zealand. This article will discuss the basic concepts of restorative justice and the various ways in which restorative justice has been implemented in states such as Vermont. California's recent adoption of restorative justice as part of its penal code in 2017 has provided a much-needed impetus for implementing restorative justice in this State. Restorative justice programs could be used for the rehabilitation and reentry into the community of large numbers of inmates who were transferred from prisons and held in county facilities, due to the passage of California's Public Safety Realignment Act of 2011. Increasing public awareness and promotion of the understanding of restorative justice principles and practices will help us move towards a more humane and sustainable approach for dealing with crime and public safety.

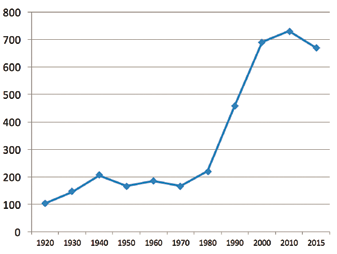

The U.S. today is a very different country from what it was in 1972, in terms of its incarceration practices and population. In 1972, there were about 300,000 people in jails and prisons and the rate of incarceration was 161 prisoners to 100,000 U.S. residents.1After a relatively stable incarceration rate which hovered around 110 prisoners to 100,000 U.S. residents from 1925 to 1972, the incarceration rate grew rapidly after 1972. Between 1980 to 2000, it increased three-fold from 220 prisoners for each 100,000 U.S. residents to 690 prisoners for each 100,000 U.S. residents.2 The U.S. incarcerated population (i.e., individuals held in state prison or local jail) has experienced an explosive increase from 474,368 inmates in 1980 to 2,173,800 inmates in 2015. According to 2016 statistics published in the World Prison Brief by the Institute for Criminal Policy Research (ICPR), the U.S. still has the world's largest prison population at 2,121,600 prisoners and highest rate of incarceration at 655 prisoners per 100,000 residents.3 The world's most populous nation, China, has about 1,649,804 prisoners with a rate of incarceration of 118 prisoners per 100,000 residents while New Zealand has a rate of incarceration of 214 prisoners per 100,000 residents.4 A huge gap also exists between the incarceration rates in the U.S. and those of its neighboring countries, Canada and Mexico. Based on the 2016 World Prison Brief, Canada's rate of

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 43]

incarceration is 114 prisoners per 100,000 residents, while Mexico's rate of incarceration is about 164 prisoners per 100,000 residents.

Although public awareness is changing, and new sentencing policies and recent decreases in U.S. prison populations have reversed the upward trend in incarceration, some analysts note that the slow rate of decline in prison population could mean that it will take 88 years for the prison population to return to its 1980 level.5 Professor Michael Tonry of the University of Minnesota has pointed out that there has been no major legislation to unwind mass incarceration or rebuild U.S. sentencing systems, although the severity of repeat offender laws has been moderated, standards for parole release eligibility have broadened and prisoner reentry programs have been created and treatment programs expanded.6 No state has repealed a three-strikes law, life without parole, truth-in-sentencing law or created a broad-based mechanism for assessing the need for continued confinement of prisoners serving excessive sentences.7

In 2010, Congress appropriated funds to the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) to launch the Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) in a public-private partnership with Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew) and other non-profit organizations to help states' policy makers use data-driven approaches to curb correction spending, reduce recidivism and improve public safety.8 According to the June 2018 update from the Council of State Governments, so far 30 states have participated in JRI since 2010.9 JRI has been funded by a modest federal budget, starting at $10 million in 2010, peaking at $27.5 million in 2014-2017 and reducing slightly to $25 million in 2018. It has met with unqualified success achieving one of its main objectives of curbing prison or corrections spending. The Urban Institute reports that 28 states participating in JRI from 2010 to 2016 have reported more than $1.1 billion in savings and invested more than $446 million in criminal justice reform efforts.10

Ironically, the truth-in-sentencing laws enacted by states in the 1990's were propelled by federal funding for building additional prisons and jails authorized by Congress through the Violent Crime Control & Law Enforcement Act of 1994, buoyed by public sentiment for offenders to serve a large portion of their sentences.11 One of the key factors holding back the immediate repeal of such laws could be the high recidivism rate of former prisoners, based on a BJA Special Report published in 2014 on the pattern of recidivism of prisoners released in 2005 from 30 states over a five-year period from 2005 to 2010.12 Recognizing that decades-long upward spiraling spending on prison construction and harsh sentencing laws did not lower recidivism rates, the approach of JRI has been to provide support for participating states to invest in evidence-based policies and practices to promote rehabilitation of those incarcerated and improve public safety.13 The data and findings on the effects of the states' shift towards justice reinvestment in community-based treatment and services, problem-solving courts, oversight councils and other reform measures are still being collected.14

Some legal scholars have argued that change in our criminal justice system does not mean just change in sentencing practices, but also change in U.S. cultural traditions and public attitudes.15 In advocating for sentencing reform, Professor Tonry pointed out that the laws passed from 1984 through 1996 "attempted to remove compassion, empathy, and recognition of human weakness—something we all recognize in ourselves—from the processes by which punishments are imposed and administered."16 Implementing sentencing reforms to reduce the prison population would not be sufficient to instill compassion and empathy in our criminal justice system. Adopting a restorative justice approach could provide this missing link.

Although restorative justice processes have been practiced in victim-offender mediation programs begun by Mennonite communities in Canada and the U.S. since the 1970's, it was only in the 1990's that there was an enormous growth in restorative justice programs around the world.17 Restorative justice has become increasingly popular in response to the harsh and highly impersonal type of retributive justice meted out against criminal offenders.18 Howard Zehr, a leading proponent of restorative justice, explains that restorative justice involves a shift in worldview that focuses on crime as "a violation of people and relationships," necessitating the administration of justice involve the search for solutions promoting the repair of community relations, reconciliation and reassurance. Thus, a restorative justice model would more easily incorporate rehabilitation programs and processes for reintegration of prior offenders into society.

Restorative justice is a community-based concept of justice. Many restorative justice initiatives are based on volunteerism and significant numbers of community members participate in their operation.19 Restorative justice practitioners such as attorney Marina Sideris, who serves on the Restorative Justice Institute of Maine, consider restorative justice to be a locally-based practice.20 Ms. Sideris cites both her state and the federal Bill of Rights which provide that a criminal trial is before "an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed," as supporting the notion that criminal

[Page 44]

justice involves inherently local processes.21 Specifically, when a crime is committed, then discretionary local actors make choices, such as the local police who decide how to respond and whether to charge the offender, local prosecutors who decide whether to prosecute and what the proper punishment should be and local jurors who decide what constitutes proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Those who are experienced in restorative justice practice believe that the strength and efficacy of restorative justice programs depend on the...

To continue reading

Request your trial