Patents and Antitrust in the Pharmaceuticals Industry

| Publication year | 2021 |

| Author | By DeForest McDuff, Ph.D., Mickey Ferri, Ph.D., and Noah Brennan, M.I.A. |

By DeForest McDuff, Ph.D., Mickey Ferri, Ph.D., and Noah Brennan, M.I.A.1

Patent rights are a core element of protecting innovation in the United States. The pharmaceutical industry is often identified as an example of the patent system working well, by compensating innovators for research and development and then allowing competition after innovators have been rewarded. Over the past 10-15 years, however, there has been increased concern of anticompetitive behavior associated with prolonged patent protection, which has led to a number of antitrust lawsuits attempting to restrain the long duration of exclusivity.

Antitrust enforcement efforts have had mixed success to date, depending primarily on whether the efforts are focused on patent-based strategies versus market-based strategies. Patent-based strategies relying purely on seeking additional patents on existing products, such as evergreening and patent thickets, have been difficult to address in the antitrust domain because of constitutional rights to seek patents. By contrast, market-based strategies impacting the availability of competing products, such as product hopping and reverse payments, have shown to be more susceptible to antitrust enforcement. The distinction in effectiveness appears to stem from the legal system's stronger ability to identify anticompetitive conduct in the market domain, compared to the pursuit of patentable innovations in good faith.

Ultimately, antitrust enforcement efforts in the last decade have shown that foundational principles of protecting competition through the antitrust laws serve the public interest well, with some room for policy improvement around the edges, not necessarily limited to antitrust law, in order to address aspects of market exclusivity that are specific to the pharmaceutical industry.

[Page 127]

This article proceeds as follows: Section 2 describes the economic framework for patent protection and why it has caused potential for certain economic incentives and unintended consequences. Section 3 describes antitrust enforcement as a framework for limiting potential excesses of the patent system that may cause anticompetitive behavior. Section 4 provides a public policy evaluation of antitrust enforcement and other policy initiatives designed to limit extreme outcomes that may be socially undesirable. Section 5 concludes.

The grant of exclusive property rights vested in patents has a long history, tracing back to medieval guild practices in Europe.2 The very first Article of the U.S. Constitution established the intellectual property clause providing for the patent system, which instructs Congress to "promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries" (emphasis added).3 The Patent Act of 1790 originally included a patent term duration of 14 years from patent issuance.4

The legal system has reinforced the effectiveness of the patent system, developing rules and procedures to enforce the rights of patentees and their assignees. For example, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, the intellectual property expert of the early courts, offered this perspective in Ex parte Wood: "[T]he inventor has ...a property in his inventions; a property which is often of very great value, and of which the law intended to give him the absolute enjoyment and possession ... involving some of the dearest and most valuable rights which society acknowledges, and the constitution itself means to favour."5 Congress has adapted the law to improve the system, including the Patent Act of 1836 that introduced an examination system that is still in use today, whereby each patent application is scrutinized by technically trained examiners to ensure that the invention conforms to the law and constitutes an original advance in the state of the art.6

The term length of issued patents has also undergone revision over time. The Patent Act of 1836 originally increased the term from 14 years to 21 years from issuance. In 1861, the term was changed to 17 years. The signing of the 1994 Uruguay Round Agreements Act changed the patent term from 17 years from the date of issuance to 20 years from the earliest filing date, which remains active today.7

[Page 128]

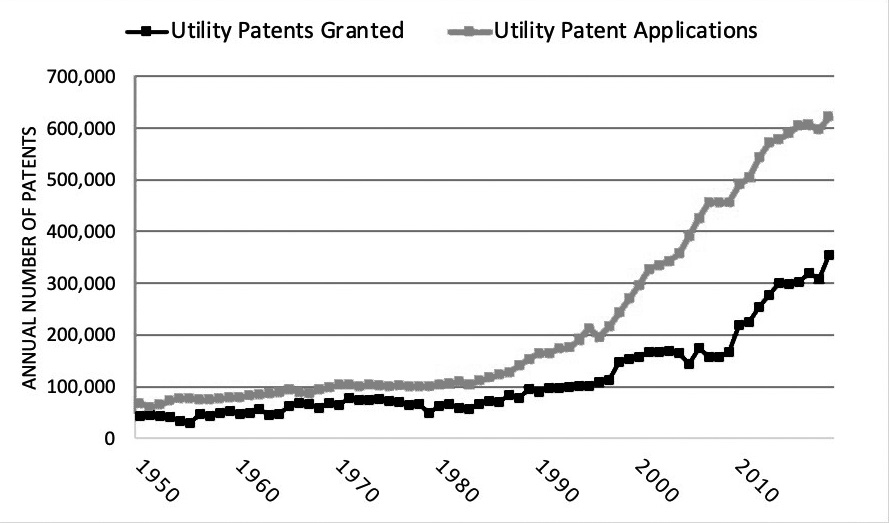

In the last few decades, the number of patents and patent applications has increased dramatically. See Figure 1. For example, data from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) show that the number of utility patent applications increased from just over 100,000 in 1979 to over 600,000 in 2019. Similarly, the number of utility patents granted grew from nearly 50,000 in 1979 to more than 350,000 in 2019. Said another way, there were nearly 1,000 new patents granted per day in 2019.8 In the context of the increasing volume of patents in recent years, it is worth evaluating the role of patents in the overall economy, including the economic trade-offs between patent holders, consumers, and potential competition.

Figure 1. U.S. Patent Activity (1950-2019)

Image description added by Fastcase.

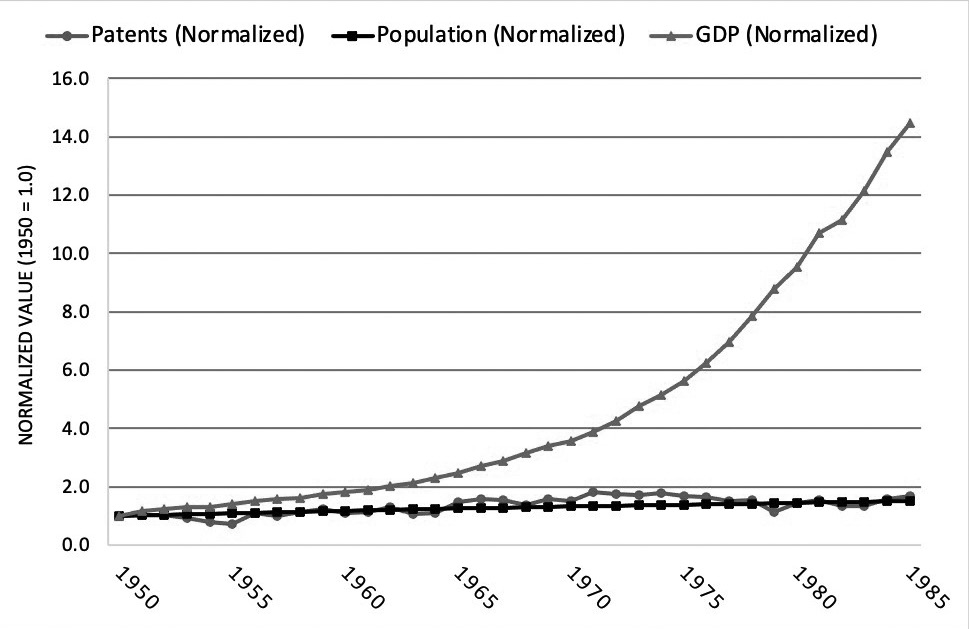

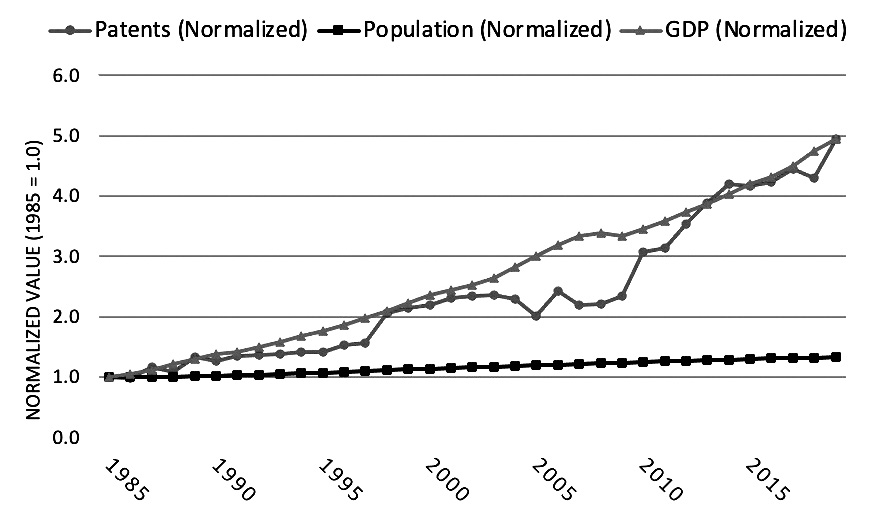

A comparison between patent grants, U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), and population growth show that growth in patents has become more correlated with growth in GDP in recent years, with both growing faster than the population.9 This trend can be seen by separating the data into two time periods: (1) 1950 to 1985 and (2) 1985 to 2019.10 First, from 1950 to 1985, GDP growth far outpaced both patent growth and population growth. See Figure 2.A. Annual GDP in 1985 was 14.5 times its 1950 level, while annual patent grants were 1.7 times their 1950 level and population was 1.5 times its 1950 level. By comparison, from 1985 through 2019, GDP growth closely aligned with patent growth, while population growth was far lower. See Figure 2.B. Using 1985 as the base year,

[Page 129]

the 2019 levels of both GDP and patent grants were 4.9 times their 1985 levels, while population growth was just 1.3 times its 1985 level.

The pattern that growth in patents has been aligned with GDP growth beginning in 1985, yet not in the prior period, is generally consistent with commentary and analysis from a number of sources on the increasing contribution of capital (which includes intellectual property such as patents) and decreasing contribution of labor to the U.S. economy over the past few decades.11

Figure 2.A Patents, Population, and GDP (1950-1985)

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 130]

Figure 2.B Patents, Population, and GDP (1985-2019)

Image description added by Fastcase.

As a matter of economics, patent rights are typically justified based on allowing inventors to recoup returns on investments in research, development, and regulatory approval.12 Economically, a profit opportunity is larger for a patent holder who has the exclusive right to make, use, or sell a patent protected product as compared to a profit opportunity in a competitive market, with competition from other suppliers. The large potential profit opportunity from a patented drug with high demand can incentivize research and development, which can lead to scientific and medical advances that benefit consumers and patients. Data from the USPTO indicate that patents related to "Pharmaceuticals and Medicines" comprise approximately 5% of all utility patents granted.13

Patent protection in pharmaceuticals is of particular importance because pharmaceutical research and development costs for individual drugs can be substantial, with many drugs costing billions of dollars and a decade or more to bring a new drug to market. One study published in JAMA in 2020 found that the median capitalized research and development investment to bring a new drug to market was estimated at $985.3 million and the mean

[Page 131]

investment was estimated at $1.3 billion.14 Other studies have reported similar findings, including estimated mean costs of developing a single new therapeutic agent in the multiple billions of dollars when all economic costs are included, with recent estimates in economic literature and medical literature of $2 to $3 billion per new drug.15

In addition to the monetary research and development costs, substantial time typically passes from the initial drug discovery, research & development, and patent filing, through clinical trials and regulatory approval until the eventual product launch. One study in 2016 indicated that the process of drug development can take 15 years, with 3-5 years of drug discovery, 1-2 years of pre-clinical time, 6-7 years of clinical trials, and 1-2 years of regulatory approval.16 Another study found that the average time from the start of clinical testing to marketing approval was 8.1 years.17 Further, there is an economic risk that the drugs may never make it to market. One study found that the overall probability of clinical success (i.e., the likelihood that a drug that enters clinical testing will eventually be approved) was just 12%.18

In pharmaceuticals, the period of exclusive patent protection can sometimes be limited if the duration of development is long. For example, if a product launches 13 years after the earliest filing date, the patent holder may have limited years of exclusivity to follow. From a profit maximization perspective, the patent holder will often have strong economic incentives to make as much profit as possible during this period of exclusivity. When generic competition enters...

To continue reading

Request your trial