PART 2 - CHAPTER 4 Investigation of Criminal Behavior

| Jurisdiction | United States |

Chapter 4 Investigation of Criminal Behavior

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

■ Explain the importance of due process of law and to illustrate how it affects the work of police and prosecutors.

■ Describe how police go about discovering and investigating criminal behavior.

■ Explain when and why search warrants are sometimes needed, as well as when and why they aren't.

■ Describe how law enforcement personnel gather and preserve physical and documentary evidence.

INTRODUCTION

In Part 1 of this book, we discussed the purpose, organization, and major principles that underlie our criminal justice system. These topics are typically referred to as "substantive criminal law" because they relate to what the general public can or cannot legally do. In Parts 2 and 3, on the other hand, we explore the procedural side of criminal law, where the focus is on the various stages involved in criminal prosecutions and the tasks performed by participants in the criminal justice system.

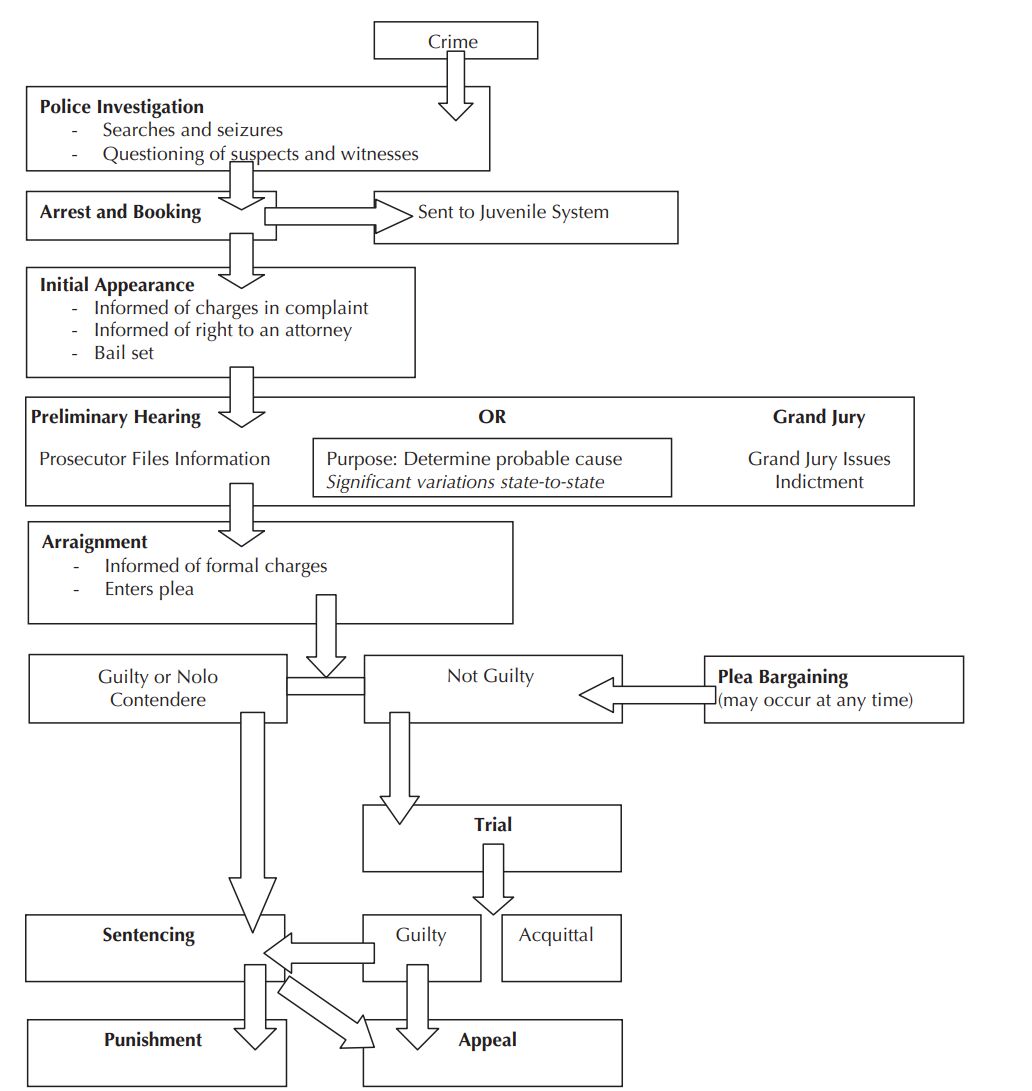

In reading this and the chapters that follow, you should find it helpful to refer to the overview of the various stages of the criminal justice process that is shown in Figure 4.1. Note, however, that some of these details vary from one jurisdiction to another. For example, only about half the states have a mandatory grand jury system. Also, be aware that the stages may be accelerated or even combined in certain types of situations.1 Additionally, note that there are many shortcuts and diversions built into the criminal justice system, and charges can be dropped at any time along the way. Where plea bargains are involved, the trial stage is skipped and the case moves directly to the corrections stages of the criminal justice process.

Figure 4.1 Stages of the Criminal Justice Process

This chapter concentrates on the role played by police and other law enforcement personnel in identifying the people who commit crimes, gathering the evidence required to justify prosecuting them, and placing them under arrest. The other chapters in this section will focus on the roles played by prosecution and defense attorneys in preparing cases for trial.

It is also important to understand that in performing their duties, law enforcement officials must act in ways that are consistent with the due process requirements of the U.S. and state constitutions.

A. CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES OF DUE PROCESS

The investigation and prosecution of criminal behavior must be conducted in ways that do not violate basic constitutional rights set forth in the Fourth, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

1. FIFTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS: DUE PROCESS OF LAW

The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states, "No person shall . . . be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law"; and the Fourteenth Amendment states, ". . . nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law. . . ." However, since the Constitution does not define what "due process" means, the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court determine its meaning. "Due process" usually refers to the series of procedures that governments must follow before they can deprive anyone of life, liberty, or property. This is called procedural due process. However, there is another type of due process, called substantive due process, which refers to the requirement that government cannot deprive anyone of life, liberty, or property where the law being violated is found to be arbitrary or unreasonable.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court overturned the sexual assault conviction of actor/comedian Bill Cosby on due process grounds. As you read the following excerpts from the court's opinion in the Cosby case, compare the rights of the defendant to the interests of the prosecution and victim.

...Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. William Henry Cosby, Jr. Supreme Court Pennsylvania 252 A.3d 1092 (PA 2021) OPINION

In 2005, Montgomery County District Attorney Bruce Castor learned that Andrea Constand had reported that William Cosby had sexually assaulted her in 2004 at his Cheltenham residence. Along with his top deputy prosecutor and experienced detectives, District Attorney Castor thoroughly investigated Constand's claim. In evaluating the likelihood of a successful prosecution of Cosby, the district attorney foresaw difficulties with Constand's credibility as a witness based, in part, upon her decision not to file a complaint promptly. D.A. Castor further determined that a prosecution would be frustrated because there was no corroborating forensic evidence and because testimony from other potential claimants against Cosby likely was inadmissible under governing laws of evidence. The collective weight of these considerations led D.A. Castor to conclude that, unless Cosby confessed, "there was insufficient credible and admissible evidence upon which any charge against Mr. Cosby related to the Constand incident could be proven beyond a reasonable doubt."

Seeking "some measure of justice" for Constand, D.A. Castor decided that the Commonwealth would decline to prosecute Cosby for the incident involving Constand, thereby allowing Cosby to be forced to testify in a subsequent civil action, under penalty of perjury, without the benefit of his Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. Unable to invoke any right not to testify in the civil proceedings, Cosby relied upon the district attorney's declination and proceeded to provide four sworn depositions. During those depositions, Cosby made several incriminating statements.

D.A. Castor's successors did not feel bound by his decision and decided to prosecute Cosby notwithstanding that prior undertaking. The fruits of Cosby's reliance upon D.A. Castor's decision—Cosby's sworn inculpatory testimony—were then used by D.A. Castor's successors against Cosby at Cosby's criminal trial. We granted allowance of appeal to determine whether D.A. Castor's decision not to prosecute Cosby in exchange for his testimony must be enforced against the Commonwealth.

. . . Nearly a decade after D.A. Castor's public decision not to prosecute Cosby, the Commonwealth charged Cosby with three counts of aggravated indecent assault stemming from the January 2004 incident with Constand in Cosby's Cheltenham residence. On January 11, 2016, Cosby filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus seeking dismissal of the charges based upon the former D.A. Castor's purported promise—made in his representative capacity on behalf of the Commonwealth—that Cosby would not be prosecuted. . . .

From February 2-3, 2016, the trial court conducted hearings on Cosby's habeas petition, which it ultimately denied. . . .

For the reasons detailed below, we hold that, when a prosecutor makes an unconditional promise of non-prosecution, and when the defendant relies upon that guarantee to the detriment of his constitutional right not to testify, the principle of fundamental fairness that undergirds due process of law in our criminal justice system demands that the promise be enforced. Prosecutors are more than mere participants in our criminal justice system. [P]rosecutors inhabit three distinct and equally critical roles: they are officers of the court, advocates for victims, and administrators of justice. As the Commonwealth's representatives, prosecutors are duty-bound to pursue "equal and impartial justice," and "to serve the public interest." Their obligation is "not merely to convict," but rather to "seek justice within the bounds of the law." . . .

Considered together, these authorities obligate courts to hold prosecutors to their word, to enforce promises, to ensure that defendants' decisions are made with a full understanding of the circumstances, and to prevent fraudulent inducements of waivers of one or more constitutional rights. Prosecutors can be bound by their assurances or decisions under principles of contract law or by application of the fundamental fairness considerations that inform and undergird the due process of law. The law is clear that, based upon their unique role in the criminal justice system, prosecutors generally are bound by their assurances, particularly when defendants rely to their detriment upon those guarantees. . . .

[W]hen a defendant relies to his or her detriment upon the acts of a prosecutor, his or her due process rights are implicated. The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 9 of the Pennsylvania Constitution mandate that all interactions between the government and the individual are conducted in accordance with the protections of due process. We have explained that review of a due process claim "entails an assessment as to whether the challenged proceeding or conduct offends some principle of justice so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked as fundamental and that defines the community's sense of fair play and decency." . . .

As a reviewing court, we accept the trial court's conclusion that the district attorney's decision was merely an exercise of his charging discretion. As we assess whether that decision, and the surrounding circumstances, implicated Cosby's due process rights, former D.A. Castor's post-hoc attempts to explain or characterize his actions are largely immaterial. The answer to our query lies instead in the objectively indisputable evidence of record demonstrating D.A. Castor's patent intent to induce Cosby's reliance upon the non-prosecution decision. . . .

D.A. Castor's press release, without more, does not necessarily create a due process entitlement. Rather, the due process implications arise because Cosby detrimentally relied upon the Commonwealth's decision, which was the district attorney's ultimate intent in issuing the press release. There was no evidence of record indicating that D.A. Castor intended anything other than to induce Cosby's reliance. Indeed, the most patent and obvious

To continue reading

Request your trial