Judges of Color: Examining the Impact of Judicial Diversity on the Equal Protection Jurisprudence of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

| Publication year | 2019 |

| Author | By Kristine L. Avena* |

MCLE SELF-STUDY ARTICLE

(Check end of this article for information on how to access 1.0 self-study credit.)

This article was first published in the Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly on November 1, 2018.

By Kristine L. Avena*

Kristine L. Avena is an attorney in immigration law.

For too many people . . . law is a symbol of exclusion rather than empowerment.1

- Former Attorney General of the United States, Eric Holder, 2002

[Page 1]

Article III, section 1 of the Constitution states, "[t]he judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish."2 This imperative provision of the Constitution establishes the judiciary branch and maintains the balance of powers within the federal government. At a time when the executive branch is banning religious minorities from traveling into the country3 and stripping children away their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border,4 the courts have become the last resort for many during this critical period of history. However, for much of America's history, the legal system has been devoid of the compassion and empathy needed for judges to fully comprehend the impact of their decisions on ordinary people.5 People of color, who have historically faced unique experiences because of racial discrimination and its legacy, are often victims of this need for empathy.6 Thus, much like the fundamental equality that emanates from a diverse Congress,7 the participation of diverse judges in the judiciary is vital to the assurance of fairness, legitimacy, and due process in decision-making.

From slavery to civil rights to affirmative action, America's history has been plagued with the issue of race. The federal bench is no exception. For almost two centuries, the highest court of the nation did not represent the public that it served. It was not until 191 years after the founding of America that the U.S. Supreme Court Bench enjoyed the presence of a diverse judge with Justice Thurgood Marshall.8 Then in the 1970's, due mainly to President Jimmy Carter's initiative to appoint more minority judges, the racial composition of the federal judiciary began to diversify significantly.9 However, while the number of minority judges increased in the past two centuries, the federal courts still do not reflect today's society. The total composition of Article III judges currently includes: 3.4% Asians, 10.6% Hispanics, and 14.2% African Americans, compared to 72% Whites.10 This composition is still less diverse than the current population of the United States, which is 6% Asian, 18% Hispanic, 12% African American, and 61% White.11 In fact, a study by political science Professors Rorie Solberg and Eric N. Waltenburg reveals that the federal bench is becoming less diverse even as the United States is growing more diverse.12

This article aims to determine how the presence of minority judges on the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit impacts the Equal Protection doctrine.13 The Ninth Circuit, which consists of Alaska, Arizona, California, Guam, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Northern Mariana Islands, Oregon, and Washington,14 is the largest and most diverse federal appellate bench in the nation.15 This article shows that a Ninth Circuit judge's race is important in providing procedural and substantive contributions to the federal bench. Diverse judges use their life experiences to ensure that every person is heard and treated fairly, thereby instilling public confidence in the legitimacy of the court and educating their colleagues on the panel on the unique issues that minority groups encounter. However, this article also proves that race alone does not influence the court's equal protection jurisprudence due to two major factors: the Ninth Circuit, as an appellate court, is bound by the decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court, and judges are committed to their duty to "faithfully and impartially" uphold the Constitution.16

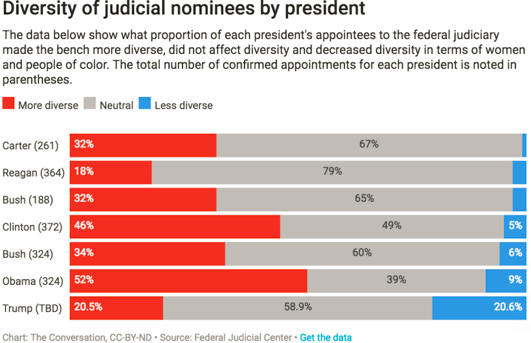

Image description added by Fastcase.

Exhibit A. Chart illustrating how previous Presidents have increased judicial diversity in the past two decades, but President Trump's nominees are resulting in a less diverse judiciary.

[Page 2]

This article applies the definition of a "minority" from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ("EEOC").17 According to the EEOC, a minority is "the smaller part of a group."18 These groups consist of: American Indian or Alaskan Natives, Asian or Pacific Islanders, Blacks, and Hispanics.19 Currently, there are 13 racially diverse judges out of 48 judges on the Ninth Circuit: Carlos Tiburcio Bea, Patrick J. Bumatay, Consuelo Maria Callahan, Jerome Farris, Ferdinand F. Fernandez, Kenneth K. Lee, Mary H. Murguia, Jacqueline H. Nguyen, Richard A. Paez, Johnnie B. Rawlinson, A. Wallace Tashima, Kim McLane Wardlaw, and Paul J. Watford.20 Approximately 27% of the 48 judges on this federal appellate bench are diverse, thus comprising of 3 African Americans, 4 Asians, and 6 Hispanics. Individually, these judges have unique life experiences that they bring to the bench—Judge Bea faced the threat of deportation,21 Judge Nguyen fled her home country as a refugee during the Vietnam War,22 and Judge Tashima was interned as a Japanese American during World War II.23 This article addresses the impact that those distinctive life experiences bring to the bench.

I. THE EQUAL PROTECTION DOCTRINEThe Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states, "[n]o State shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."24 This study focuses on the Equal Protection Clause because it was designed to ensure that the Constitution protects minorities from prejudice in the political process.25 When analyzing an equal protection claim, courts apply either a standard of heightened scrutiny, which includes both strict scrutiny and intermediate scrutiny, or they apply rational basis review.26Heightened scrutiny applies when a court has reason to "suspect" a classification reflects prejudice against a "discrete and insular" minority, rather than an informed policy choice.27 28

There are two situations where one might see the impact of a judge's race in evaluating equal protection claims. First, in order to pass strict scrutiny, a classification must be the least discriminatory means or narrowly tailored to serve a compelling interest.29 Although there are prior examples of how the U.S. Supreme Court has applied this standard of review, its ambiguous and broad language gives judges much flexibility in its application. Second, if there is a classification that has not yet been established by law, judges have the authority to apply specific factors to determine whether a group constitutes a "suspect" class before applying strict scrutiny.30 Judges have the discretion to assess the following factors: historical and current discrimination, political power, immutability of the characteristic, Congress' sensitivity to the classification, and whether the trait correlates to an ability.31

II. BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGYPast research on judicial decision-making has focused on the impact of a variety of factors, but not on the impact of race alone. There are countless studies examining the role of intersectionality or gender on the federal bench,32 decision-making in state courts or federal circuit courts as a whole,33 and judicial voting patterns in favor or against a plaintiff or defendant.34 These studies have found that a judge's race only has an impact on particular issues. For example, Black judges are more sensitive to issues relating to racial discrimination because of their racial identity and firsthand experiences with racial discrimination.35 In addition, Latino judges are more sympathetic in immigration cases, not due to racial discrimination, but rather, due to "the shared view of opportunities that life in the United States presented to their immigrant families."36 Similarly, Asian judges are also more sympathetic to immigrants, but because of their firsthand experiences with racism and xenophobia.37 Among others, one consistent result is that minority judges are more sympathetic to civil rights issues such as gender and racial discrimination.38

[Page 3]

The theory underlying this analysis is substantive representation, which posits that "when circumstances and discretion allow, public officials will act to benefit members of groups of which they are a part."39 A limitation of this theory with respect to appellate judges is that they are unelected and accorded life tenure, so they are not easily affected by public opinion.40 Therefore, while this political insulation may lead some to do more to benefit their group, others may hide behind such safeguards and maintain the status quo. Additionally, Supreme Court scholars Harold Spaeth and Jeffrey Segal's attitudinal model connects with this study's focus on judicial decision-making. The attitudinal model claims that judges decide cases based on personal ideology rather than adherence to the law.41 However, a major limitation of the attitudinal model is its assumption that ideology and legal interpretation are mutually exclusive in judicial decision-making. Merely because a judge's ideology impacts one's decision does not mean that their ideology conflicts with the law.

III. FINDINGS BASED ON PERSONAL INTERVIEWSA substantial component of this study incorporates...

To continue reading

Request your trial