HEDGING TRANSACTIONS FOR THE OIL AND GAS PRODUCER

| Jurisdiction | United States |

(Nov 1995)

HEDGING TRANSACTIONS FOR THE OIL AND GAS PRODUCER

Denise M. DeForest

Holme Roberts & Owen LLC

Denver, Colorado

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION

II. TYPES OF HEDGING TRANSACTIONS

A. Overview

B. Swaps as a Hedging Device

1. Swaps

2. Swap Examples

3. Basis Swaps

C. Caps, Floors and Collars as Hedging Devices

1. Caps and Floors

2. Collars/Fences/Range Forward

3. Collar Example

4. Participating Collars

5. Participating Collar Examples

D. Options

III. USING DERIVATIVE TRANSACTIONS

A. Exchange Transactions versus Over-the-Counter Transactions

B. Hedging Proved Producing Properties

C. Managing the Risk of Derivative Transactions

1. Market Risk

2. Credit Risk

3. Liquidity Risk

4. Legal Risk

5. Operational Risk

[Page 10A-ii]

IV. DOCUMENTATION OF OVER-THE-COUNTER HEDGING TRANSACTIONS

A. Generally

B. Elements of the Master Agreement Form

1. "Default Under Specified Transaction" versus "Cross-Default"

2. "Events of Default" versus "Termination Events"

3. "First Method" versus "Second Method"

4. "Netting" versus "Set-Off"

5. Representations, Warranties and Covenants

V. SELECT LEGAL ISSUES AFFECTING HEDGING

A. Bankruptcy Concerns

B. Accounting Treatments

C. Preemption of State Gaming and "Bucket" Laws

———————

[Page 10A-1]

I. INTRODUCTION.

There are many reasons to hedge crude oil and natural gas production, the primary one being to control market price risk.1 A hedging transaction properly constructed should help stabilize a producer's overall income. In an acquisition context, if the acquisition costs of the properties are to be financed, hedging can insure that there will be sufficient cash flow from the expected volumes of production being acquired (or from some percentage of those volumes) to meet fixed obligations. Many lenders in the oil and gas area require at least some hedging in order to assure themselves that their borrowers will be able to meet their interest payments and principal amortization schedule. The more highly leveraged a company is, the less ability it has to deal with declines in market prices compared to an unleveraged company.2 Thus hedging is even more important to the highly leveraged company.

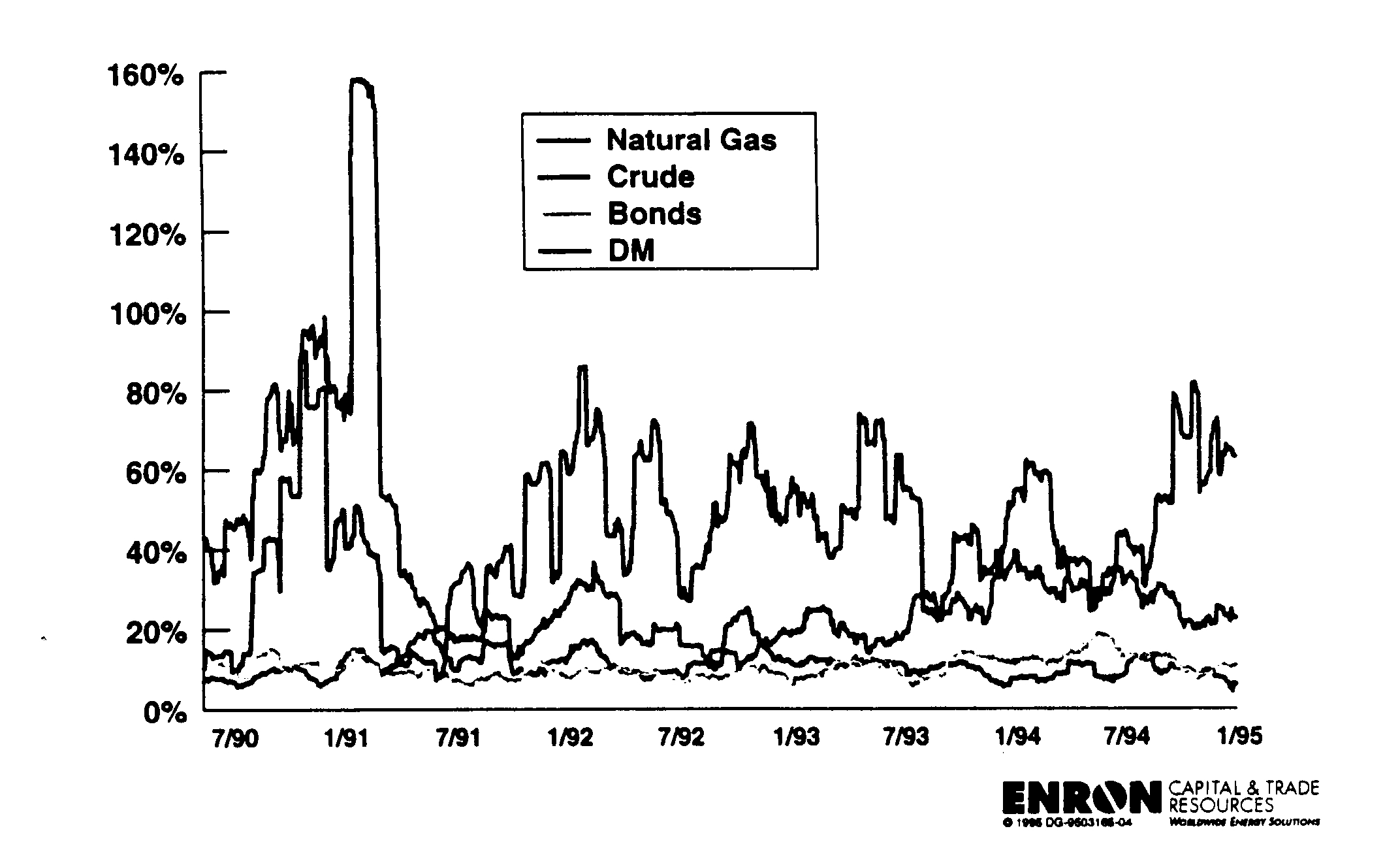

The price of every commodity fluctuates, but natural gas has the highest price volatility of any traded commodity in the world today.3 The potential for wide swings in a producer's income due to changes in the market, however, can be minimized by using risk management tools to hedge production.

This paper will review the types of hedging transactions available, discuss their use and structures, explain some of the risks involved and review some of the legal issues surrounding their documentation and use.

[Page 10A-2]

Historical Commodity Price Volatility

II. TYPES OF HEDGING TRANSACTIONS.

A. Overview

A hedging transaction refers to a risk management tool involving the purchase or sale of any one of several types of instruments, each of which is intended to protect against adverse rate or market price fluctuations, such as derivative transactions, futures contracts or forward contracts.

Derivative transactions are sometimes defined as financial contracts whose value is derived from the value of the underlying commodity, such as spot prices for gas or crude oil. These transactions are usually cash settled, and include swaps, caps, floors, collars and options. Derivatives are a type of financial transaction which, although tied to the market values of an actual commodity, are

[Page 10A-3]

generally based upon "notional volumes" of that commodity. The parties agree to a commodity volume, e.g., 30,000 barrels of crude oil or 30,000 million British thermal units ("MMBtu") per month of natural gas, and make a cash settlement of the transaction based upon that amount, but the commodity is never actually delivered. A producer would enter into a hedging transaction to offset the risk of falling prices. An end user would enter into a hedging transaction to offset the risk of rising prices. The institutional counterparty in an off-exchange transaction would generally enter into a variety of transactions that would offset the risk of each other, so that the profit for the institutional counterparty is in the spread and fees.

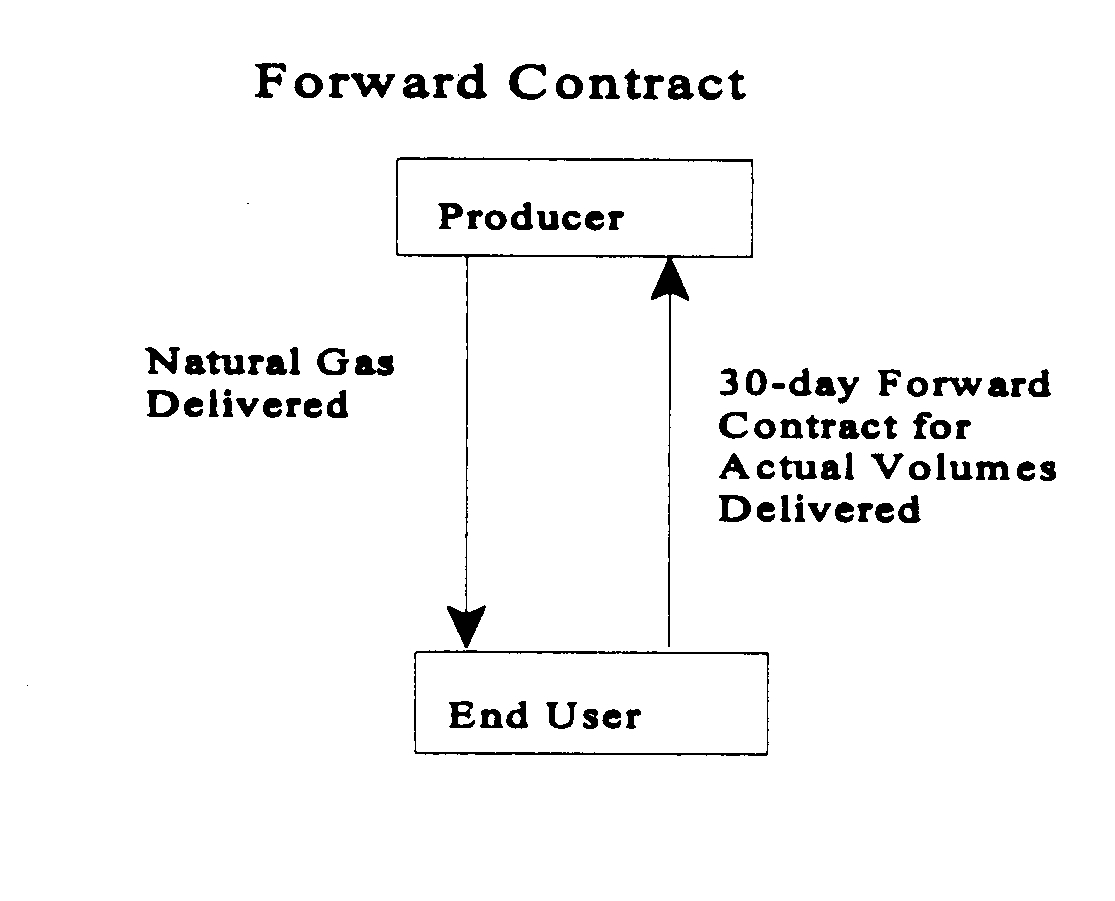

Futures contracts are standardized contracts traded on a board of trade, such as the New York Mercantile Exchange ("NYMEX"), to buy or sell a commodity for delivery at a certain future time for a certain price on standardized terms for quantity, quality, delivery point, term, etc. These contracts are usually closed out before actual delivery of the commodity is required. A forward contract will contain customized provisions and is privately negotiated rather than being traded on a board of trade. A forward contract is usually settled by actual delivery of the commodity. A typical 30 day gas purchase contract is a forward contract.4

[Page 10A-4]

Futures contracts are traded on the commodities markets and regulated by the Commodities Futures Trading Commission ("CFTC"), whereas a forward contract is not so regulated.5 The Commission has issued final rules which expressly exempts certain transactions in crude oil, condensates, natural gas and natural gas products from most commodity regulatory requirements on the grounds that the transactions are forward contracts.6

Although hedging transactions can lock in a fixed price or range of prices for the producer for the referenced notional volumes, hedging transactions do not eliminate the many other risks facing a producer, such as reserve risks, title issues, etc.

B. Swaps as a Hedging Device.

1. Swaps. A swap is "an agreement between two parties to exchange a series of payments measured by different interest rates, exchange rates or prices, with payments calculated by reference to a principal base (notional amount)."7 A swap creates two different payments streams over time, with the payments being

[Page 10A-5]

tied, at least partially, to uncertain and unknown future market price movements.8 The swap is a derivative product and not a physical commodity transaction; the volumes referenced are notional volumes. The swap contract does not require either counterparty to the swap transaction to deliver gas or crude oil; instead, each party to the swap agreement has a payment obligation based upon the notional volumes. A swap transaction will lock in a fixed rate for the producer for the notional volumes selected.

If a gas producer wishes to hedge against a drop in natural gas prices, it can enter into a swap agreement with a counterparty in which the counterparty agrees, at a future date, to pay the producer a fixed price based upon a notional volume of gas. The producer, in exchange, agrees to pay the counterparty a floating price based upon these notional volumes. The floating price is determined by reference to a specified gas price index such as NYMEX, prices at specified future dates, or an average of prices over a specified period of time.

If the index price (the floating price) is greater than the fixed price, the producer will pay the counterparty the difference between the index price and the fixed price. If the fixed price is greater than the index price, i.e., the index price has dropped below the agreed upon fixed price, the counterparty will pay the producer the difference. This arrangement produces one of two results: if the price of natural gas drops below the fixed price, the counterparty will pay the producer the difference based upon the notional volumes. If, on the other hand, the price of natural gas rises over time, the producer will pay the increase above the fixed price to the counterparty based upon the notional volumes.

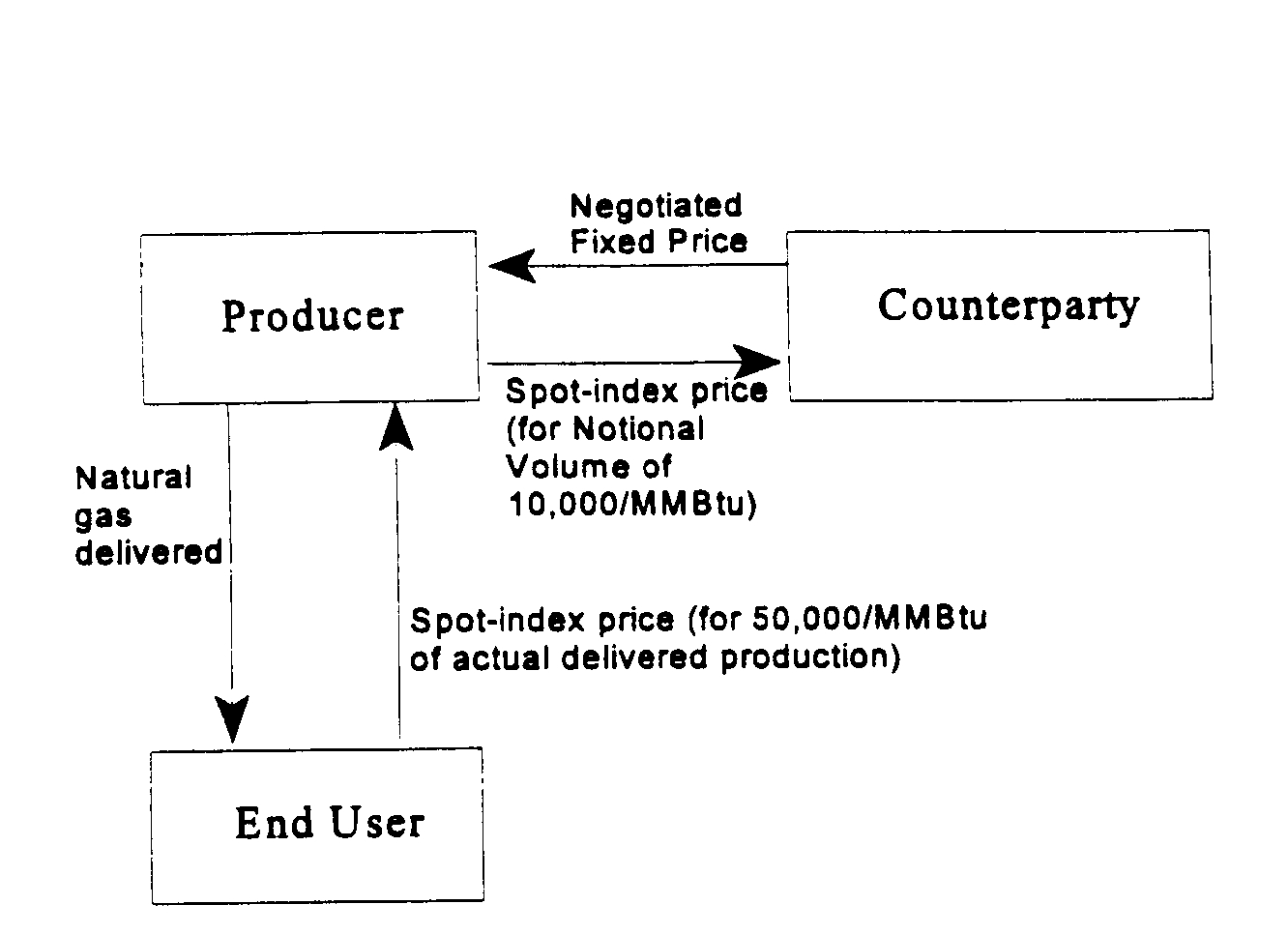

2. Swap Example. A natural gas producer determines that it needs to guarantee a price of $2.35/MMBtu for at least 20% of its 50,000 MMBtu of production over the next eighteen months in order to cover its fixed operating costs for that period. The producer continues to sell its actual production to end users at the spot index prices. The producer also enters into an eighteen month swap agreement with an institutional counterparty for a fixed price of $2.35/MMBtu for a notional volume of gas of 10,000 MMBtu (20% of the producer's monthly production). The producer agrees to pay the counterparty a floating price based upon an agreed upon NYMEX index price for the 10,000

[Page 10A-6]

MMBtu of gas.9 The deal requires cash settlement each month for the difference between the current index price for a particular month and the fixed price of $2.35/MMBtu.

If the published spot index price for one month is $2.00/MMBtu, then the producer receives $0.35/MMBtu times the notional volumes of 10,000 MMBtu, or $3,500 from the counterparty. That payment, combined with actual sales of the natural gas for $2.00/MMBtu will result in the producer receiving $2.35/MMBtu for the 10,000 MMBtu (or 20% of its gas) subject to the swap. The producer will receive $2.00/MMBtu for the other 80% of its production not subject to the swap transaction.

If, however, the spot index price rises above the $2.35/MMBtu mark, then the producer pays the counterparty the difference between the index price and the fixed price for the notional volumes. In a month where the spot index price is $2.50/MMBtu, for example, the producer pays the counterparty $0.15/MMBtu times the notional volumes of 10,000 MMBtu, or $1,500. The producer will sell 100% of its gas (50,000 MMBtu) to the end user for $2.50/MMBtu, but the producer's cash payment to the counterparty of $0.15/MMBtu for the notional volume of 10,000 MMBtu, results in the producer effectively receiving $2.35/MMBtu for 20% of its production and $2.50/MMBtu for the other 80%.

[Page 10A-7]

Producer Swap Example *

3. Basis Swaps. Swaps can also be constructed to hedge the "basis risk" in a...

To continue reading

Request your trial