Copyright Commentary

| Citation | Vol. 42 No. 2 |

| Publication year | 2017 |

| Author | WILLIAM J. O'BRIEN |

WILLIAM J. O'BRIEN

One LLP

More than a year ago, I suggested that it might be "time for our highest court to clarify the scope of copyright protection for clothing, cars, and other useful articles...."2 One of the two cases on which I focused was Varsity Brands, Inc. v. Star Athletica, L.L.C., in which the Sixth Circuit held that cheerleader uniform features such as stripes, chevrons, and color blocks "can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects" of the uniforms and thus are protected by copyright.3 I quoted the dissenting Sixth Circuit judge who had said that, "until we get much-needed clarification, courts will continue to struggle and the business world will continue to be handicapped by the uncertainty of the law."4 I concluded that, "[a]bsent Supreme Court intervention, there is no clear limit to the expansion of copyright protection for product designs."5

The Supreme Court granted certiorari to review the Sixth Circuit's decision and "resolve widespread disagreement over the proper test" for copyrights in features of useful articles.6 Now that the Court has announced its decision, where do we stand? The Court has indeed provided a specific test for determining what features may be copyrightable, but the test posits a nebulous question of what can be "identified and imagined apart from the useful article."7 Its application is debatable in practice. Moreover, neither the Supreme Court's majority nor its dissent have succeeded in formulating a test that fully accomplishes the results they assert. The law in this area remains underdeveloped and potentially troublesome.

Pre-1976 Copyrights in Useful ArticlesThe original Copyright Act, enacted in 1790, protected only "map[s], chart[s], [and] book[s]" - all two-dimensional works.8 In 1870, Congress expanded copyright protection to encompass certain three-dimensional works of art.9 And the 1909 Copyright Act broadened protection for three-dimensional works.10 Over time, the availability of copyright protection for three-dimensional objects has greatly increased the potential for encroachment of copyrights into the designs of useful articles.

To be sure, a distinction between copyright-eligible works of art and uncopyrightable commercial materials had been asserted even with regard to printed materials. In Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., the Supreme Court rejected the argument that posters advertising a circus were not protected by copyright, because they had "no other use than that of a mere advertisement, and no value aside from this function...."11 Justice Holmes decided, "A picture is none the less a picture and none the less a subject of copyright that it is used for an advertisement."12 Bleistein largely put an end to attempts to exclude copyrights in commercial printed materials,13 but the application of copyright to three-dimensional useful articles remained problematic.

Household lamps are useful articles that often incorporate three-dimensional artwork. The lamps as a whole are lighting devices, but their stands and bases are often decorative. In Rosenthal v. Stein, the plaintiffs had registered copyrights in four statuettes, which they incorporated into lamps.14 The defendants made and sold copies of the plaintiffs' lamps.15 Their proffered justification for this copying was that, "while a copyrighted work of art may not be copied and sold without the consent of the copyright holder, yet when the object copyrighted is combined with something else and the resulting combination is a utility, the combination is not a copyrighted work of art and is not and cannot be protected by the copyright law."16 But the Ninth Circuit concluded that the plaintiffs' unquestioned copyrights in the statuettes "cannot be affected by the gratuitous use of the creations by strangers for ornamental supports for a household utility...."17

While the defendants in Rosenthal conceded the validity of the plaintiffs' copyrights, the Supreme Court addressed that issue in another lamp-copyright case, the seminal Mazer v. Stein.18 Here again, the plaintiff had registered copyrights in statuettes that it used and sold as lamp bases. The Court upheld the validity of these copyrights, rejecting the defendants' argument that "that congressional enactment of the design patent laws should be interpreted as denying protection to artistic articles embodied or reproduced in manufactured articles."19 On the contrary, the Court held that, in adopting the 1909 Copyright Act, "Congress intended the scope of the copyright statute to include more than the traditional fine arts."20 The Court found "nothing in the copyright statute to support the argument that the intended use or use in industry of an article eligible for copyright bars or invalidates its registration."21

[Page 32]

The 1976 Act's Protection for Separable Features of Useful ArticlesThe current, 1976 Copyright Act covers a wide range of two- and three-dimensional "original works of authorship," including "pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works."22 But the Act limits copyright protection of "useful articles," which it defines as "having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information. An article that is normally a part of a useful article is [also] considered a 'useful article.'"23 The Copyright Act provides that "[t]he design of a useful article...shall be considered a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work only, if, and only to the extent that, such design incorporates pictorial, graphic or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article."24

Before the Court's decision in Star Athletica, the Copyright Act's requirement that copyrightable features be separable from "the utilitarian aspects of the article"25 was generally regarded as encompassing both "physical" and "conceptual" separability.26 In his dissenting opinion, Justice Breyer provides examples of both. As an example of physical separability, Justice Breyer depicts a lamp with a light fixture held by a brass rod inserted on a base and - separately mounted on the base - a porcelain sculpture of a Siamese cat:

Justice Breyer's Example of Physical Separability27

"Obviously, the Siamese cat is physically separate from the lamp, as it could be easily removed while leaving both cat and lamp intact. And, assuming it otherwise qualifies, the designed cat is eligible for copyright protection."28

On the other hand, one could also imagine a design in which there is no separate brass rod. "[I]nstead, the cat sits in the middle of the base and the wires run up through the cat to the bulbs. The cat is not physically separate from the lamp, as the reality of the lamp's construction is such that an effort to physically separate the cat and lamp will destroy both cat and lamp."29

Justice Breyer's Example of Conceptual Separability30

The two are integrated into a single functional object, like the similar configuration of the ballet dancer statuettes that formed the lamp bases at issue in Mazer v. Stein.... But we can easily imagine the cat on its own, as did Congress when conceptualizing the ballet dancer."31"Hence the cat is conceptually separate from the utilitarian article that is the lamp."32

Copyrighting Designs for Cheerleader CostumesStar Athletica v. Varsity Brands provides a case study in how an aggressive manufacturer of useful articles can use copyrights to hem in its competition. Varsity Brands is a powerhouse of the cheerleading industry. It "runs...cheer competitions and camps. It publishes a cheer-leading magazine and has its own online television network."33 But according to the Houston Press, "where Varsity Brands really makes its money is apparel. It owns cheerleading from head to toe; everything from the sequined uniforms on cheerleaders' backs to the big bows in their poofed-up hair."34 "Varsity has sat alone at the top (and middle and bottom) of the cheerleading pyramid ever since [2004], making more than $1.2 billion in sales according to a press release issued after private equity investment firm Charlesbank Capital Partners bought Varsity in 2014, and wielding unmatched influence over cheerleading at every level, from high school to college to competitive gyms - and, even, the courtroom."35

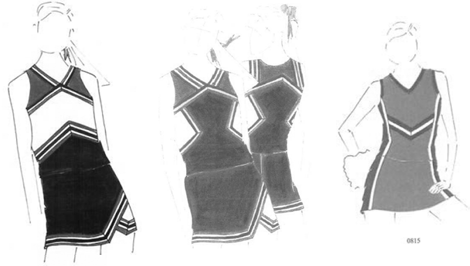

Part of Varsity Brands' strategy of dominance is evidently to pursue copyright protection. Varsity Brands companies have "more than 200 U.S. copyright registrations for two-dimensional designs appearing on the surface of their uniforms and other garments."36 As described by Justice Thomas, "These designs are primarily 'combinations, positionings, and arrangements of elements' that include 'chevrons..., lines, curves, stripes, angles, diagonals, inverted [chevrons], coloring, and shapes.'"37 He calls these "surface decorations."38 Varsity Brands sued a competitor, Star Athletica, for infringing five of Varsity's registered copyrights.39 Three of the registrations are of drawings of cheerleader uniforms on outlines of human figures:

[Page 33]

The other registrations are of photographs of cheerleader uni-forms.40

Varsity contended that Star Athletica infringed these copyrights by "cop[ying], reproduce[ing], display[ing], and distribut[ing] infringing images of these designs in its 2010 catalog and internet website" and "by incorporating the designs onto the surface of Star's cheerleading uniforms."41

The two courts that preceded the Supreme Court in considering this case took fundamentally different approaches. Their most profound disagreement was in identifying the "utilitarian aspects" of a cheerleading uniform as a preliminary step to analyzing separability...

To continue reading

Request your trial