Client-driven Estate Planning: a Different Approach to Estate Plan Design

| Citation | Vol. 9 No. 2 |

| Publication year | 2003 |

| Author | By J. Christopher Toews, Esq. |

By J. Christopher Toews, Esq.*

Recently a new client came to my office for a review of his estate plan. He was an Italian man in his late 60's who had done very well in the construction business despite having come from a poor family and having quit school after the ninth grade. His net worth at the time he saw me was over $10 million and growing.

The plan he handed me was about two inches thick and had been prepared by a prominent Los Angeles law firm. As he put it on my desk, he looked at me with obvious frustration and said, testily, "What does this goddamn thing say?"

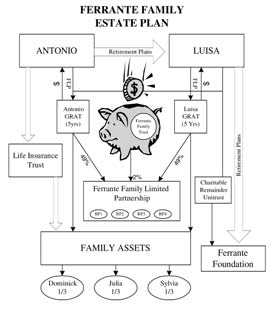

That Mr. Ferrante (not his real name) was confused by his plan is understandable. There was a fifty-page revocable trust, of course, with elaborate provisions designed to avoid or minimize income, estate and generation-skipping taxes. Then there were the usual pour-over wills, powers of attorney and advance health care directives. Also, there was a family partnership, portions of which had been transferred to grantor retained annuity trusts for Mr. Ferrante and his wife. In addition, there was a life insurance trust, a split-interest trust and a family foundation.

Somewhere in the middle of all this, hopefully, were a few sentences telling us what would happen to Mr. Ferrante's assets in the event of his death. However, finding this crucial information was so beyond Mr. Ferrante's ninth-grade reading ability that he had to hire an attorney (me) to find it for him.

The late cartoonist Rube Goldberg was famous for designing absurdly complicated machines to perform simple, everyday tasks. Regrettably, Mr. Ferrante's estate plan - and, indeed, many of today's most sophisticated estate plans - could be models for Mr. Goldberg's cartoons. The diagram I prepared of Mr. Ferrante's plan looked like this:

Image description added by Fastcase.

[Page 43]

The problem with Mr. Ferrante's estate plan was not that the documents were legally defective or that the tax planning was inappropriate for a $10 million estate. Rather, the problem was that the lawyer who designed it was so busy dealing with tax and legal issues that he forgot about Mr. Ferrante and his need to understand what it said. The end result was an unhappy client because the plan, whatever its technical merits, failed to meet the client's subjective, but very real, need to put his affairs in order.

Cases like that of Mr. Ferrante are common, and suggest that the process by which we design estate plans needs to be revisited. Our clients pay our bills, after all, and if they are not happy with our work then it is incumbent on us to find out why and address their concerns. If we don't, they will not continue to be our clients for very long. Hopefully the discussion below will suggest some of the things that we need to do.

Lawyers tend to think of an estate plan in terms of its objective goals, which typically include some or all of the following:

- Providing financial benefits for spouses, children or other loved ones;

- Contributing to favorite causes;

- Disinheriting unloved relatives;

- Avoiding or minimizing transfer taxes and administration expenses; and

- Appointing a trusted person to administer the estate upon the death or incapacity of the client.

These things are at best indirect benefits for the client, however, because they most frequently take place only after the client dies. The immediate benefit, and the driving force behind the client's desire to create an estate plan, is subjective - i.e., the peace of mind that comes with the knowledge that his or her wishes on these important matters will be honored. Mr. Ferrante was unhappy with his plan because it failed to give him closure or peace of mind - he couldn't understand it, and he was afraid that his executor might not understand it either when the time came.

The thesis presented here is that we need to understand what our clients' desires are, listen to those desires and make the satisfaction of those desires an explicit goal of the estate planning process. This may mean, among other things, that we need to rewrite our trusts to make them more concise and more understandable. It may mean that we advise the client to forego some advanced tax planning strategies for the good and sufficient reason that the client does not understand them. Lastly, it means that we should take extra care to explain the plan design and its complexities in terms that the client can understand.

The idea that the design of a product or service should take into account the subjective needs of the customer is not new. The auto industry has been known to sell cars for their sex appeal or as status symbols and not simply on the basis of economy, safety or the size of the back seat. For years, IBM sold computers which were technically inferior to competing products at premium prices because it had a more sophisticated understanding of what it was selling. One writer observed:

IBM understands. What does IBM really sell? Hardware? Software? Solutions? They sell all of those - and none of them. An old IBM advertisement says it all. "At IBM, we sell a good night's sleep."

. . . .

IBM sells certainty. In a chaotic world, with too many technological choices, no one ever got fired for buying IBM. . . . I bought certainty and a good night's sleep. I willingly paid a premium for it. . . .1

What may be new, or at least insufficiently discussed in legal literature, is the notion that these time-tested business concepts apply to attorneys, i.e., that we are in a service business, that our clients are our customers, and that we need to design and deliver our services in a way that satisfies them.

We owe our clients a duty to be competent in our drafting and tax planning, of course. But if we allow tax-planning strategies and drafting techniques to complicate our plan documents to such an extent that the client is uncomfortable with them, then we have failed to meet one of our client's most important needs. We may have benefitted the client's relatives by minimizing estate taxes, but that is secondary because it is not their money and they did not hire us. The client did, and we had best never forget that central fact.

We acknowledge that producing client-friendly, readable documents is an important goal, we will notice that this goal may conflict with other planning goals. For example, we may want to include encyclopedic powers clauses in our trusts so that the trustee will not have problems dealing with third parties (e.g., brokerage houses). However, these provisions add pages of boilerplate to the trust document and often confuse the client.2 A sensible compromise might be to provide that the trustee has all powers granted by the law of the state of administration, plus any specific additional powers deemed necessary for administration of a specific trust.3

Compromise, in any event, is inherent in the design of trusts or indeed of virtually any legal document. None of us has ever drafted a trust document that dealt with every conceivable problem - if we had, no one would have the time to read it, much less understand it. What actually happens is that we prepare a document that we believe deals with the most obvious problems, and hope that it expresses the client's intent well enough so that interpretation and applicable law will cover the matters we leave out. What is being proposed here is merely that we should make this design process and its inherent compromises explicit, and that, in general, we should tilt our design decisions in the direction of producing simpler, more readable documents.4

[Page 44]

Once it is recognized that the client's comfort level is an important goal of plan design, there are a number of steps which can be taken to increase the level of client satisfaction with the plans we prepare. Some of these are outlined below.

A. Find Out Who the Client Is

If our goal is to deliver peace of mind, we need to understand just who our client is and what his or her level of comfort is with complex legal arrangements. The most important variables are probably the client's interests and his or her level of education. Is the client an accountant with a graduate degree in...

To continue reading

Request your trial