Chapter §6.06 Traditional "Time Gap" Situations Invoking Written Description Scrutiny

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§6.06 Traditional "Time Gap" Situations Invoking Written Description Scrutiny

[a] General

The procedural context of the above example, which involved an applicant presenting a new claim during ongoing prosecution after a patent application had been filed, is a typical one for written description issues. . . .

[b] Entitlement to Filing Date of Domestic Provisional Application

The Federal Circuit's February 2017 decision in Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute v. Eli Lilly and Co. ("LAB")92 aptly illustrates the written description of the invention requirement exercising its classic priority-policing role. . . . .

[c] Entitlement to Filing Date of International Application

A March 2018 Federal Circuit decision, Hologic, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc.,102 provides another practical illustration of the written description of the invention requirement applied in its traditional priority-policing role. . . . .

The procedural context of the above example, which involved an applicant presenting a new claim during ongoing prosecution after a patent application had been filed, is a typical one for written description issues. Written description of the invention issues have traditionally arisen in "time gap" situations, when (1) new claims are added to a pending patent application or an originally filed claim is substantively amended during prosecution,87 (2) an applicant claims the benefit of the earlier filing date of a related domestic patent application88 or a corresponding foreign-origin patent application,89 or (3) an interference is declared in which the issue is support for a count in the specification of one or more of the parties.90 In these contexts, the written description of the invention requirement acts as a "priority policer," that is, the requirement is applied to ensure that later-filed claims are truly entitled to priority back to a desired earlier filing date.91

The Federal Circuit's February 2017 decision in Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute v. Eli Lilly and Co. ("LAB")92 aptly illustrates the written description of the invention requirement exercising its classic priority-policing role. During an inter partes review, petitioner Eli Lilly ("Lilly") challenged the nonobviousness of Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute's (LAB's) U.S. Patent No. 8,133,903 ('903 patent) in view of a combination of prior art references. In an attempt to remove the references as prior art,93 LAB asserted that its '903 patent was entitled to the 2002 filing date of Provisional Application No. 60/420,281, from which the '903 patent (filed for in 2004) claimed priority under 35 U.S.C. §119(e). The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) determined that the '903 patent was not entitled to the §111(b) provisional application's filing date, and the Federal Circuit affirmed. The disclosure of LAB's provisional application did not provide a sufficient written description of the method of treatment invention later claimed in LAB's '903 patent; a skilled artisan would have been required to draw five different assumptions not stated in the provisional application to arrive at the dosage regimen recited in the '903 patent claims. At best, the information in the provisional application would have required the artisan to consult uncited prior art and then make the appropriate assumptions. The LAB decision illustrates that written description disclosure must be present in the parent (here, provisional) application itself, and cannot be based simply on information and inferences drawn from references not cited therein.

More specifically, LAB's claimed invention was a method of treating penile fibrosis by administration of a type 5 phosphodiesterase (PDE5) inhibitor, at a dosage of up to 1.5 mg inhibitor per kg of a patient's body weight per day, for not less than 45 days.94 PDE5 inhibitors were known in the prior art for on-demand treatment of erectile dysfunction (e.g., the inhibitors sildenafil and tadalafil are present in the Viagra and Cialis products), but before LAB's invention they had not been utilized for long-term cure of underlying tissue fibrosis.

The PTAB determined that the claimed method of the '903 patent would have been obvious in view of three prior art references: Montorsi, Whitaker, and Porst, the first two of which petitioner Lilly cited as 35 U.S.C. §102(b) (2006) references. The Board found that the references in combination taught, inter alia, the claim-recited dosage of up to 1.5 mg/kg/day.

LAB attempted to remove Montorsi and Whitaker as prior art by asserting that the '903 patent was entitled to the 2002 filing date of its provisional application. Notably, the provisional application did not explicitly disclose the claim-recited dosage of "up to 1.5 mg/kg/day." However, LAB's expert witness contended that the provisional application's disclosure of a study of PDE5 inhibitors in rats explicitly taught dosing the rats with 100 mg/L of a PDE5 inhibitor (i.e., sildenafil) in drinking water. According to LAB's expert, one of ordinary skill in the art could have scaled up this dosage to the corresponding human dosage by reliance on a conversion method published in a 1966 paper by Emil Freireich.95

The Circuit rejected LAB's argument for priority to the provisional application. It observed that LAB depended on five different assumptions that the skilled artisan would have to make. The first four assumptions were that the artisan would know (1) the average daily water intake of the rat model used, (2) the average weight of the rat model used, (3) the average weight of an adult human male, and (4) the average height of an adult human male. The Board had concluded that these four variables were not knowable from the provisional application's specification, but would "at best" require the artisan to look to the prior art and make assumptions. The Federal Circuit agreed with the Board that this was "not enough to establish priority," citing the court's 1997 holding in Lockwood v. Am. Airlines, Inc.96 that it is "not sufficient for purposes of the written description requirement of § 112 that the disclosure, when combined with knowledge in the art, would lead one to speculate as to modifications that the inventor might have envisioned, but failed to disclose."97

The fifth assumption required by LAB's argument for priority to its provisional was that the skilled artisan would rely on the Freireich method to convert the rat study dosage disclosed in the provisional to a human dosage for therapeutic treatment of fibrosis with PDE5 inhibitors as required by the '903 patent. The Federal Circuit again rejected the argument that a skilled artisan would have gone so far. It observed that the Freireich reference "was not disclosed in the provisional application, is nearly a half a century old, and was based on measurement of toxicity of anticancer agents."98 Importantly, LAB could not "rely on standalone references that it failed to incorporate in the provisional application in order to make out its priority claim," because " 'it is the disclosures of the [provisional] application[] that count," not those of uncited references.' "99

The Board had correctly held that the calculation proposed by LAB's expert did not satisfy the requirement of written description disclosure in the provisional application. Proof of priority could not be based simply on "information and inferences drawn from uncited references. . . ."100 Accordingly, LAB's '903 patent was not entitled to the October 2002 priority date of the provisional application and LAB could not remove the cited references as prior art on that basis.101

A March 2018 Federal Circuit decision, Hologic, Inc. v. Smith & Nephew, Inc.,102 provides another practical illustration of the written description of the invention requirement applied in its traditional priority-policing role. Notably, the patented technology in Hologic was a medical device (and its use), technology that the Circuit agreed was "predictable." It affirmed the PTAB's determination in an inter partes reexamination that the written description requirement was satisfied, allowing the patentee to claim priority to its earlier-filed published PCT application to remove it as invalidating §102(b) prior art. The Hologic court applied Ariad's "reasonably conveys" test to mean, at least in the case on review, that the earlier disclosure need not necessarily or explicitly disclose (e.g., by depicting in drawings) every claim-recited element. The court supported its interpretation by relying in part on 35 U.S.C. §113, which does not require drawings of an invention if they are not necessary for the understanding of the patented subject matter.

More specifically, U.S. Patent No. 8,061,359 ('359 patent), owned by Smith & Nephew, Inc. and Covidien LP (collectively "S&N"), claimed an endoscope and a method to remove tissue from a patient's uterus. The claimed method recited the use of an endoscope that included a "permanently affixed" "light guide" in one of two channels.103

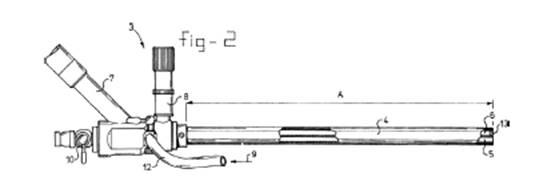

Three figures of the '359 patent illuminated the disputed claim term "light guide." First, Figure 2 of the '359 patent (shown here as Figure 6-2) depicted the full endoscope device, including the two claimed channels 5 and 6, one of which had to have a light guide permanently fixed inside. The '359 patent specification explained that viewing channel 6 has a lens 13 and can be connected to a light source 8.

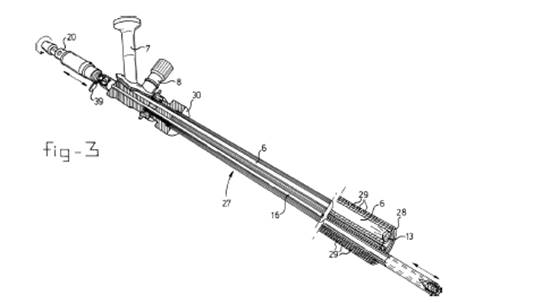

Figure 3 of the '359 patent (shown here as Figure 6-3) depicted a cut-away of Figure 2, including viewing channel 6 and lens 13, and illustrated light going from the lens into the viewing channel.

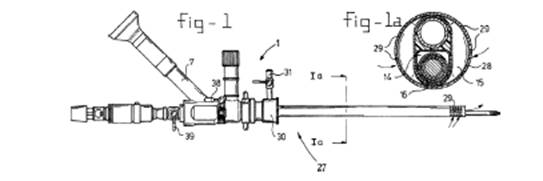

Finally, Figure 1a of the '359 patent (shown here as Figure 6-4) depicted a cross section of the endoscope shaft, including the two channels from Figure 2—viewing channel 6 and main channel 5.

To continue reading

Request your trial