CHAPTER 3 - § 3.04

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§ 3.04 EXAMPLE CASE 3: READER'S DIGEST ASSOC. INC. V. CONSERVATIVE DIGEST, INC. (D.C. CIR. 1987)

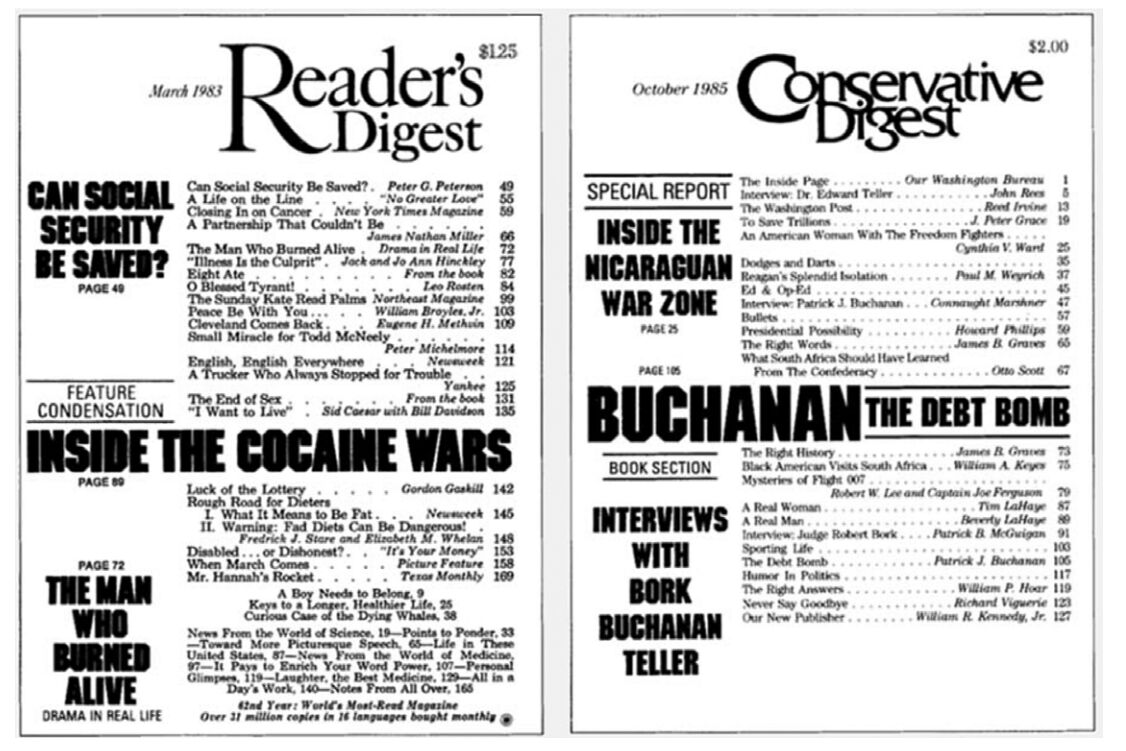

In August 1985, William R. Kennedy Jr. acquired Conservative Digest and decided to change the appearance of the magazine.99 The new format, which was shown at the National Press Club, "strongly resembled" the cover of Reader's Digest in "size, shape, and graphic design."100 Scott Stanley Jr., the editor-in-chief of Conservative Digest, acknowledged the "similar appearance" and stated at the reception: "If Conservative Digest looks like Reader's Digest, I'm sure that Wally (the founder of Reader's Digest) and Lila (his wife) are somewhere up there says, "That's great, kids Keep it up.'"101

The respective covers for the Reader's Digest and Conservative Digest magazines are shown below:102

In response to this change in format, Reader's Digest requested that Conservative Digest cease publication of the magazine.103 Conservative Digest agreed to do so starting with the December 1985 issue, thus publishing the October 1985 and November 1985 issues with the format at issue.104 Notwithstanding the agreement, Reader's Digest brought suit against Conservative Digest, claiming that Conservative Digest violated Reader's Digest's trade dress under section 43(a) of the Lanham Act.105

The district court found that the trade dress of Reader's Digest magazine had acquired secondary meaning because it had been published with the same format for six years and there was "extensive promotion" of the magazine during this period.106 Further, the district court found that Conservative Digest intentionally copied the format of Reader's Digest magazine, which would likely mislead consumers.107 Accordingly, the district court found in favor of Reader's Digest, and Conservative Digest appealed.108

The DC Circuit began its analysis by defining trade dress as "the total image of a product," which "may include features such as size, shape, color or color combinations, texture, and graphics."109 In order to prevail on a trade dress claim, the plaintiff was required to show "that the trade dress of its product is primarily non-functional," "that the trade dress of its product has acquired secondary meaning" such that the "public has come to recognize the trade dress as associated with the plaintiff's product," and "that the defendant's trade dress is likely to confuse or mislead consumers."110 With respect to the confusion element, the plaintiff must show that the defendant's behavior caused the consumers "to think that the defendant's product is the plaintiff's product" or "to think that the two products [came] from the same source."111

The court did not find error with the district court's findings. The main support for this...

To continue reading

Request your trial