Chapter §25.02 The Paris Convention

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§25.02 The Paris Convention

[A] Introduction

The Paris Convention is the oldest body of multinational industrial property22 law with the widest membership. The Paris Convention first came into force in 1883; the United States has been a signatory to the Paris Convention since 1903. The Convention has been modified through various revisions; the current version is that which was revised in Stockholm in 1967.23 The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in Geneva, Switzerland, a specialized agency of the United Nations,24 administers the Paris Convention. As of May 2020, 177 countries were signatories to the Paris Convention.25

The Paris Convention is the basic international agreement dealing with the treatment of foreigners under national patent laws. It addressed some, but not all, of the obstacles to international patenting discussed above. For example, the Paris Convention did not set up any "substantive minima" for industrial property protection, meaning that it was silent as to the technical criteria for patentability or the types of subject matter for which patents should be available. In fact, a country could be a signatory to the Paris Convention while not granting patents at all; Switzerland and the Netherlands did not have patent systems in the latter part of the 19th century, although both countries were signatories to the Paris Convention.26

The Paris Convention was fairly silent on the propriety of protectionist measures. For example, the original version of the Paris Convention specifically allowed the continued existence of national working requirements and said nothing at all about compulsory licensing. Later versions of the Paris Convention contain only very limited restrictions on the ability of signatory countries to grant compulsory licenses.27

Despite the absence of substantive minima and its few limitations on protectionist measures, the Paris Convention did establish two key rights that made it far easier to obtain patent protection in foreign countries than had previously been the case. These rights, which have become cornerstones of all subsequent international patent agreements, are the principles of national treatment and the right of priority.

[B] National Treatment

Article 2 of the Paris Convention implements the principle of national treatment.28 National treatment simply means that each signatory country to the Paris Convention must treat foreign nationals seeking industrial property protection in that country as well as (or, optionally, better than) it treats its own nationals. For example, the national treatment principle prevents the United States from charging U.S. nationals a patent application filing fee of $300 while demanding a filing fee of $600 from nationals of other countries. The foreign nationals must be charged the same filing fee of $300 (or, optionally, a lower fee).

The drafters of the Paris Convention chose national treatment over the competing principle of "reciprocity." In a system governed by reciprocity principles, Country A treats foreign nationals of Country B in the same manner as Country B treats the nationals of Country A, regardless of how Country A treats its own nationals (or how it treats the nationals of Country C). For example, if Country B charges nationals of Country A a patent application filing fee of $1,000, then under a reciprocity system Country A will charge the nationals of Country B a patent application filing fee of $1,000 (regardless of whether Country A charges its own nationals only $500 or charges the nationals of Country C a filing fee of $2,000).

Implementing a reciprocity-based system imposes significant administrative costs and burdens, because Country A must become intimately familiar with the patent laws and procedures of every other country and vice versa. These heightened burdens led the drafters of the Paris Convention to reject the principle of reciprocity in favor of national treatment.

[C] Right of Priority

The other key right established by the Paris Convention is the right of priority, found in Article 4 of the convention.29 This right greatly simplifies the process of obtaining industrial property protection in multiple signatory countries. By filing a patent application on an invention in a single Paris member country (typically in the inventor's home country, because it is the most convenient), an inventor can obtain the benefit of that same initial filing date (referred to as her priority date) in any other Paris Convention signatory countries in which she files additional patent applications on the same invention within the period of time called the priority period. For patents, the relevant priority period is 12 months, starting from the date of filing of the first application.30

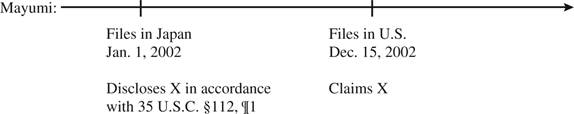

For example, consider an inventor named Mayumi, a Japanese national, who filed a patent application on her invention X in Japan (a signatory to the Paris Convention) on January 1, 2002. On December 15, 2002, Mayumi filed an application for the same invention X in the USPTO. Assume that the Japanese application adequately supports the invention that Mayumi is claiming in her U.S. application in accordance with 35 U.S.C. §112, ¶1 (2000), and that Mayumi makes a formal claim for the benefit of her foreign priority date under 35 U.S.C. §119 (the U.S. implementation of the Paris Convention right of priority, discussed infra31).

If these criteria are satisfied, the USPTO examiner will treat the U.S. application as if it had been filed on January 1, 2002, for purposes of examining it against the prior art for novelty and nonobviousness. In practical terms this means that the U.S. application will "relate back" to the Japanese filing date; the USPTO will ignore any intervening, potentially patentability-destroying developments that occurred between January 1 and December 15 of 2002. Such developments could include, for example, the publication of a description of the same invention or the filing of another U.S. patent application on the same invention, whether these events were triggered by Mayumi or a third party.

The foreign priority right means that such intervening events are not considered prior art against Mayumi's U.S. application. Under pre-America Invents Act of 2011 (AIA) rules, Mayumi's January 1, 2002, Japanese filing date would be treated by the USPTO as Mayumi's presumptive invention date in the United States for purposes of applying the novelty provisions of 35 U.S.C. §102 (2000) (i.e., §§102(a), (e), and (g))32 and 35 U.S.C. §103 (2000) (nonobviousness). Figure 25-1 illustrates this practice.

Following implementation of the AIA's first-inventor-to-file system on March 16, 2013,33 the foreign priority date is treated as the U.S. application's "effective filing date," assuming all requirements for attaining the foreign priority right are satisfied.34

Notably, claiming the benefit of one's Paris Convention priority date does not reduce the term of protection by the length of the priority period.35 In the above example, Mayumi's U.S. patent would expire 20 years from its earliest effective U.S. filing date, not any earlier foreign priority date. Thus, the U.S. patent would expire on December 15, 2022. Claiming entitlement to the benefit of a Paris Convention foreign priority date is an exclusively positive benefit. Mayumi benefits from being able to avoid any potentially patentability-destroying activity that occurred during the priority period (i.e., events that took place between January 1, 2002, and December 15, 2002), while not facing the start of the 20-year patent term clock until her actual U.S. filing date of December 15, 2002.36

The ultimate fate of Mayumi's Japanese application is not relevant to the status of her U.S. application. The Japanese application need not issue as a Japanese patent in order for Mayumi to claim the benefit of its filing date for her U.S. application. All that the Paris Convention requires is that the priority application be "[a]ny filing that is equivalent to a regular national filing under the domestic legislation of any country of the Union or under bilateral or multilateral treaties concluded between countries of the Union. . . ."37 The convention defines a "regular national filing" as "any filing that is adequate to establish the date on which the application was filed in the country concerned, whatever may be the subsequent fate of the application."38

[D] U.S. Implementation of the Paris Right of Priority: 35 U.S.C. §119

Section 119(a)–(d) of the U.S. Patent Act is the domestic implementation of the Paris Convention right of priority in patent cases. These provisions of 35 U.S.C. §119 were added to U.S. patent law by virtue of the 1952 Act, but similar provisions existed in predecessor statutes since 1903.39

Section 119 provides in pertinent part that

(a) An application for patent for an invention filed in this country by any person who has, or whose legal representatives or assigns have, previously regularly filed an application for a patent for the same invention in a foreign country which affords similar privileges in the case of applications filed in the United States or to citizens of the United States, or in a WTO member country, shall have the same effect as the same application would have if filed in this country on the date on which the application for patent for the same invention was first filed in such foreign country, if the application in this country is filed within twelve months from the earliest date on which such foreign application was filed. . . . 40

This rather complex statutory language can be parsed into a few basic points. Section 119(a) confers an important benefit to U.S. patent applicants who have previously filed a patent application on the same invention in another country. In sum, 35 U.S.C. §119(a) means that if an applicant first files a patent application in a foreign country that is a WTO member or...

To continue reading

Request your trial