CHAPTER 2 CASE LAW RESEARCH

| Jurisdiction | United States |

Chapter 2 CASE LAW RESEARCH

A. OVERVIEW

Everyone who enters law school becomes acquainted with the basic principles of law and legal logic in the substantive courses. The study of substantive law trains the student to recognize the legal issues confronted in practice on a day-to-day basis. An equally important task, however, is to locate the sources of that substantive law. The lawyer, then, needs to analyze carefully each legal problem first to determine what type of law is involved and then to find the law quickly and accurately. The importance of this legal research is underscored by the American Bar Association's Code of Professional Responsibility which requires understanding of both the principles of law and how to find them.1

Fortunately, legal research is a systematic process that lends itself to a step-by-step approach. The purpose of this guide is to explain and re-enforce these processes through the use of checklists which will help simplify the research process.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, doing legal research over the years has changed as there has been a greater move toward electronic research. This is particularly true in finding cases as some law libraries have discontinued print versions for materials that are available electronically.2 But during the transition period, it is important for the researcher to be comfortable with both print and electronic copy as both are still being published and probably available.

| THE PATTERN OF LEGAL AUTHORITY | |||

| LEVELS OF AUTHORITY | Federal | State | Local |

| TYPES OF AUTHORITY | Constitution Statutes Cases Administrative Rules & Regs. | Constitution Statutes Cases Administrative Rules & Regs. | Municipal Charters Ordinances Administrative Rules & Regs. |

[1] Types of Authority

The American legal system is comprised of law from several levels of government and various types of authority. Legal authority is divided into two major categories: they are primary and secondary authority. These types of authority affect the research process because of their relative importance.

[a] Primary Authority

Primary authority is the law itself, and therefore, the most desirable source of legal research. Primary authority consists of written constitutions, statutes, and court decisions. These authorities are in turn designated as either mandatory or persuasive.

Primary mandatory authority consists of the constitution, statutes, and decisions of the highest level of courts from a jurisdiction. For example, all trial and intermediate appellate courts in California must follow the California constitution, statutes, and Supreme Court of California decisions. Primary persuasive authority consists of appellate court decisions from other jurisdictions. However, the constitutions or statutes from other jurisdictions are neither mandatory nor persuasive. Because primary authority is the most important source, the researcher should always try to locate primary authority to support the client's position.

[b] Secondary Authority

Secondary authority is all other written expressions of the law. As a rule, secondary authority explains or expounds upon primary authority. It is generally used if there is no primary authority to support or explain the legal issue. Examples of secondary authority include treatises, law review or bar journal articles, and legal encyclopedias.

| TYPES OF AUTHORITY | |

PRIMARY: | State and Federal Constitution Statutes Cases — either mandatory or persuasive |

SECONDARY: | State and Federal All other written expressions of the law |

The purpose of this chapter is to analyze primary authority in the form of cases, that is, judicial decisions, and to discuss the methods of finding that case law. The following chapters will discuss the other forms of primary and secondary authority.

[2] The Foundation

The Anglo-American judicial system is founded on the concept of the "common law" and the doctrine of stare decisis. The term common law refers to the judicial decisions by English courts which were the basis of law for the states and countries originally settled and controlled by England. Thus, the term is distinguished from that body of law from other judicial systems such as Roman law, civil law, and canon law. Because American judicial decisions came from English common law, they are also referred to as the common law. The term, however, does not include statutes that are passed by the various federal and state legislatures.

From this concept of the common law, the doctrine of stare decisis emerged. Simply stated, the court will review the facts of "our case" to determine if they are the same or substantially similar to those in previous cases. These earlier cases are referred to as precedent. If the facts are similar, then the same law will be applied. If there are some differences or distinctions in the legally significant facts, then the court will not adhere to the principle of law announced in the precedent. Instead it will apply another rule or create a new rule, which in turn may become precedent for later cases. In some cases, even where the legally significant facts are identical, the court for policy reasons may not follow the precedent. This has the positive effect of adding flexibility to our law when the needs of society change.

The doctrine of stare decisis is fundamental to the American judicial system because of three inherent advantages. First, stare decisis promotes a sense of stability to our law. This is essential if there is to be public confidence in the judicial system. Second, stare decisis provides some predictability of the outcome of the case. It is important for lawyers to be able to advise their clients with confidence, and they can do so with a measure of certainty because of this doctrine. Third, stare decisis ensures fairness by the court. This means that individuals will be treated the same way given a certain set of facts. This doctrine is important to the legal researcher because it highlights the emphasis on case law to the American legal system. Therefore, every researcher's goal is to find a case "on point." This is the ultimate achievement in legal research!

[3] The Court System

Structure and Reporting

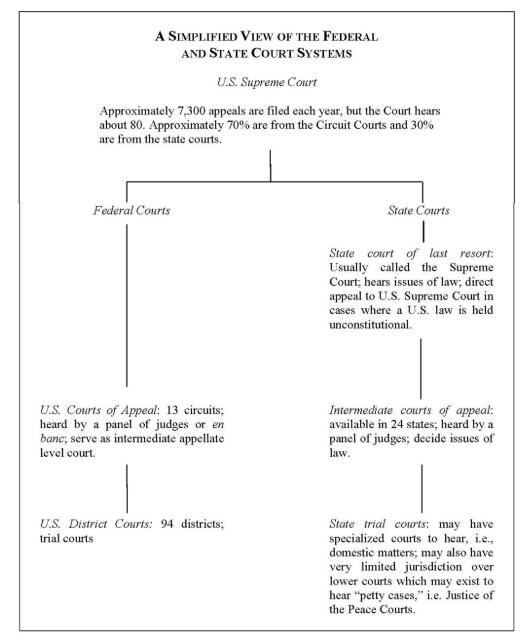

The courts on both the state and federal levels are organized in a similar structure, although the names of the courts may be different in each state. Trial courts hear testimony from witnesses or receive written documents as evidence. These courts decide matters of law and fact. As a general rule, trial court decisions are not reported. The exception to this rule is federal district court decisions; however, approximately 10-15% of these cases are reported.

If the trial court has committed prejudicial error, the case may be appealed to an intermediate court of appeals. These courts hear only issues of law and are bound by the facts that were introduced in the trial court. However, approximately 30-35% of the cases at the federal level are reported because all federal circuits have adopted rules restricting the number of published cases due to the heavy case load.

Some cases may be appealed to the court of last resort if there has been prejudicial error by the intermediate court of appeals. It should be emphasized that not all errors are grounds for appeal. The courts are not called upon to be perfect; they only need to be fair. In addition, the court of last resort is limited to questions of law that are presented in written briefs and in some instances oral arguments. All decisions from the court of last resort are reported, although in some instances, decisions involving disciplinary matters may be omitted.

Unreported Decisions

If only a small percentage of cases are reported, then most cases are "unreported" or "unpublished." The courts have criteria as to whether a case will be published or not. For example, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has Rule 47.5.1 which establishes the criteria for publishing a case. A legend on the first page of the opinion will indicate that the court has determined that this decision should not be reported.

Traditionally, unreported or unpublished cases had no precedential value. If the decision was made to not publish a case, then it was harder for lawyers to have access to the case, and as a practical matter, they were unavailable for citation. Thus, it would be unfair to allow citation to opinions that were not readily available to all lawyers. It also saved both judicial and litigant time and expense by not having read cases that may only be redundant of published cases which had precedential value.

The value of unreported cases has been a topic of discussion, debate, and controversy for years. In 2006, the United States Supreme Court adopted proposed Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 32.1. Prior to its adoption, the proposed rule was hotly debated. The final version is considered a compromise. The rule became effective on December 1, 2006 and prohibits the federal courts of appeal from disallowing citation to federal unpublished opinions that are issued on or after January 1, 2007. Rule 32.1 also states that if an unreported case is cited, then the party must file and serve a copy of the opinion with the brief or other paper in which it is cited.

Although this brings uniformity as to whether they can be cited, each circuit still has discretion as to whether unreported cases will have precedential value. For example, the current local rules for the Fifth Circuit provide that unreported cases do not have precedential value except for cases concerning the doctrine of res judicata, collateral estoppel, or law of the case.3 The local rules also provide that an unreported decision may be cited if it has persuasive value concerning a material issue which has not been decided in a reported case.

However, the electronic era had an impact on bringing change of philosophy as to unreported cases as well as the accessibility of them. Lexis and Westlaw began making unreported...

To continue reading

Request your trial