Chapter §15.04 Canons of Patent Claim Interpretation

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§15.04 Canons of Patent Claim Interpretation

A number of rules or "canons" exist for interpreting patent claims, developed primarily through case law. Some of the most important rules are individually examined below.

[A] Perspective: Person Having Ordinary Skill in the Art

Claim terms are interpreted from the perspective of the hypothetical person having ordinary skill in the art (the "PHOSITA"), rather than a judge, jury, or technical expert.110 This follows from the language of 35 U.S.C. §112, which provides that "[t]he descriptions in patents are not addressed to the public generally, to lawyers or to judges, but, as section 112 says, to those skilled in the art to which the invention pertains or with which it is most nearly connected."111

[B] General Rule: Ordinary and Customary Meaning

The general rule is that claim terms are assigned their "ordinary and customary" meaning to the PHOSITA.112 The ordinary and customary meaning of claim terms must be understood from the context of the specification and prosecution history.113 Federal Circuit decisions diverge on the specificity required of the specification and/or prosecution history to justify departure from "ordinary and customary" meaning of claim terms.

[1] Decisions Permitting Only "Stringent" Exceptions to Ordinary Meaning

One line of Federal Circuit decisions emphasizes the pervasiveness of the general rule and admits only limited, "stringent" exceptions to it.114 For example, in Thorner v. Sony Computer Ent. Am. LLC,115 the court recognized only two exceptions:

The words of a claim are generally given their ordinary and customary meaning as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art when read in the context of the specification and prosecution history. See Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2005) ( en banc). There are only two exceptions to this general rule: 1) when a patentee sets out a definition and acts as his own lexicographer, or 2) when the patentee disavows the full scope of a claim term either in the specification or during prosecution. Vitronics Corp. v. Conceptronic, Inc., 90 F.3d 1576, 1580 (Fed. Cir. 1996). 116

The Federal Circuit concluded that neither of these "exacting" exceptions applied in Thorner117 and that a district court had erred in construing disputed claim terms too narrowly. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit vacated and remanded the district court's judgment of noninfringement.

Thorner aptly illustrates the preference of at least some Federal Circuit judges for assigning a broad "ordinary and customary" meaning to claim terms, without narrowing them by reading in limitations from the specification. These judges take the view that if the resulting claim scope is too broad, this result should be dealt with via the tools of validity and/or infringement analysis rather than claim construction.118

Undoubtedly it is difficult to draw the line between properly interpreting a claim term in the context of the specification and improperly narrowing it by reading in a limitation from the specification.119 In the view of this author, however, the approach taken in some Federal Circuit decisions such as Thorner largely mirrors that of the pre-Phillips "dictionary" cases.120 The default claim interpretation is the broad "ordinary and customary" meaning of the claim term, but the Federal Circuit no longer routinely cites dictionaries as the source of that meaning. Rather, the court simply announces what it discerns to be the "ordinary and customary" meaning, in some cases seeming to discount or ignore any limiting context provided by the specification.

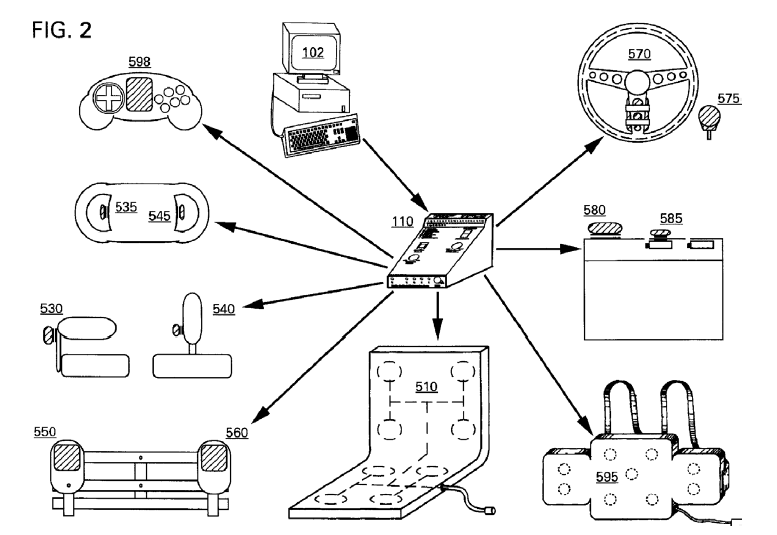

The patented technology in Thorner involved a tactile feedback system for use with computer and video games that enhanced the user's playing experience. The disclosed tactile sensation generators included a tactile sensation seating unit, a tactile sensation chest harness, and various tactile sensation actuators that would be attached to or embedded within various control inputs. For example, the system might include a seat, a vest, or a hand-held game controller that vibrated during a simulated crash in a car racing video game. One configuration of the patented system depicted a number of different actuators for generating tactile sensations:

Claim 1 of Thorner's U.S. Patent No. 6,422,941 ('941 patent) required, inter alia, a "flexible pad" and "a plurality of actuators, attached to said pad."121 Thorner sued Sony in 2009, alleging infringement of the '941 patent by the hand-held controllers and vibrating headphones in Sony's PlayStation product. After conducting a Markman hearing, the district court construed the disputed claim terms "flexible pad" and "attached."

With respect to "flexible pad," the district court observed that there was "no definition in the specification that suggest[ed] this Court depart from the ordinary meaning of the term." The district court noted that "the patent never even uses the term 'flexible pad' except in the claims." The district court also found that "many embodiments of the invention are made out of structures that would be easily flexed," such as the several embodiments that attached actuators to a "semi-rigid foam structure," a "semi-rigid flexible foam structure," or a "semi-rigid foam cushion," all of which "[could] be easily flexed." In the district court's view, there was "no reason to ignore the ordinary meaning of the term 'flexible' to include structures that generally would be considered rigid."122 The district court remarked in its Markman opinion that a steel beam is capable of being flexed, but that "no one would call it 'flexible.' "123 Thus in the district court's view, the ordinary and customary meaning of "flexible" was "capable of being noticeably flexed with ease," and the claim phrase "flexible pad" thus meant "an object or base, where such object or base is capable of being noticeably flexed with ease, including, among other things, hand-held game pad controllers that are capable of being noticeably flexed with ease."124 (The district court's interpretation seemingly would have literally excluded the accused product; after examining an accused Sony controller made of hard plastic during the Markman hearing, the district court observed that the controller was rigid and remarked that "[if] I try to flex this thing, I think that you're going to see it snap."125)

With respect to the disputed "attached to said pad" limitation, the district court admitted that this claim interpretation question was more difficult. As the district court summarized it, "the real dispute over this term [wa]s whether 'attached' should be construed [more broadly] to include embedding an actuator inside an object[,] or construed [consistent with accused infringer Sony's arguments] as limited to affixing the actuator to the outer surface."126 The district court noted the maxim that a patentee may choose to be his own lexicographer and use a term in a manner other than its ordinary meaning, but that Federal Circuit precedent recognized that an "explicit statement of redefinition" was not always necessary if the patentee "clearly expresse[d] an intent to redefine the term."127 The district court concluded that in the specification of the '941 patent, the patentee had "redefine[d] 'attached' by implication." In the district court's view, there were two reasons that "attached" could not be broadly construed to include "embedding" inside an object: "(1) the specification repeatedly and consistently use[d] the terms ["attached" and "embedded"] distinctly and with different meanings, and (2) the claims themselves differentiate[d] attaching from embedding."128

Based on the district court's construction of the disputed claim phrases, the parties in Thorner stipulated that the accused Sony devices did not infringe. The district court entered judgment of noninfringement and patentee Thorner appealed.

The Federal Circuit in Thorner vacated and remanded the judgment of noninfringement. In its view, the district court had construed the claims too narrowly, failing to adopt the correct "ordinary and customary" meaning of the disputed terms. The Federal Circuit instructed that a "patentee is free to choose a broad term and expect to obtain the full scope of its plain and ordinary meaning unless the patentee explicitly redefines the term or disavows its full scope."129 In the case at bar, neither of these two exceptions, (1) explicit redefinition, or (2) disavowal of claim scope, applied.

With respect to the "flexible pad" limitation, the Federal Circuit disagreed with the district court about the common and ordinary meaning of "flexible." The appellate court determined that, contrary to the district court's analysis, neither the claims nor the remainder of the specification required the pad to be "capable of being noticeably flexed with ease." Rather, the specification merely required that the flexible pad must have a "semi-rigid" structure. The Federal Circuit agreed with the patentee Thorner that the district court improperly narrowed the meaning of "flexible" from the plain and ordinary meaning advocated by Thorner, i.e., simply "capable of being flexed."130 "The task of determining the degree of flexibility, the degree of rigidity that amounts to 'semi-rigid,' is part of the infringement analysis, not part of the claim construction."131

With respect to the "attached" limitation, the Federal Circuit held that the "plain meaning" of "attached" applied here and encompassed either an external or an internal attachment. The district court had erred in finding that the '941 patent implicitly redefined the term to limit it to external attachment only. Although the specification of the '941 patent admittedly "never uses the word 'attached' when referring to an actuator located on the interior of a controller," this was not sufficient to rise to the level of either lexicography or disavowal.1...

To continue reading

Request your trial