CHAPTER 11 - § 11.02

| Jurisdiction | United States |

§ 11.02 FUNCTIONALITY

The Supreme Court has stated clearly that "trade dress protection may not be claimed for product features that are functional."2 A product feature is functional if it is "essential to the use or purpose of the product or if it affects the cost or quality of the device."3 Functionality is a strong defense because "functional features, like generic terms, cannot be protected even when the public associates the feature with a single source."4 This is true "for both product packaging trade dress and product design trade dress."5 Moreover, "once a design is held 'functional,' then, absent a valid utility patent, the design is available for all to copy and use as a matter of free competition."6 As noted in Chapter 1, the Lanham Act was amended in 1999 to create a "statutory presumption that trade dress features are deemed functional until proved otherwise by the party seeking trade dress protection."7

There are two rationales underlying the functionality defense.8 The first rationale accommodates "the principle that there is only one legal source of exclusive rights in utilitarian features—utility patent law."9 Indeed, "[t]he Lanham Act does not exist to reward manufacturers for their innovation in creating a particular device; that is the purpose of the patent law and its period of exclusivity."10 The second rationale is the preservation of "free and effective competition by ensuring that competitors can copy features that they need to 'compete effectively.'"11

While it may appear that the functionality defense is rather straightforward, it is not. First, there are two types of functionality—utilitarian functionality and aesthetic functionality—and they are not on equal footing. Second, the definition of functionality is the subject of "persistent controversy"12 due to quibbling over what is "essential to the use or purpose of the product" and whether whatever is deemed essential "affects the cost or quality of the device."13 Even when a product feature is held functional, "its status may later change to become non-functional."14 Thus, there is some confusion as to which test applies, and a resulting lack of uniformity among the circuit courts regarding both utilitarian functionality and aesthetic functionality. There are at least two tests—the Inwood (traditional) test and the Qualitex (competitive necessity) test. Each is discussed in detail below.15

[1]—Utilitarian Functionality

Usually, references to "functionality" in trade dress cases concern utilitarian functionality (as opposed to aesthetic functionality, discussed below). Utilitarian functionality concerns the utility of specific features of the product in dispute.16 All courts have held that determination of functionality is a question of fact, which is reviewed under a "clearly erroneous" standard.17 Prior to 1999, the circuit courts were split as to who bore the burden of proving non-functionality in unregistered trade dress cases.18 However, Congress resolved this split by inserting the following into the Lanham Act: "In a civil action for trade dress infringement under this Act for trade dress not registered on the principal register, the person who asserts trade protection has the burden of proving that the matter sought is not functional."19 The Supreme Court has interpreted this amendment as a "statutory presumption that features are deemed functional until proved otherwise."20

It bears repeating that the functionality analysis concerns the utility of specific features of a particular item, not the "the usefulness of the article overall."21 The following commentary sheds light on this fine distinction:

The true question is: is the article in this particular shape for utilitarian reasons? For example, is it shaped this way because it makes it easier to hold, cheaper to make, more durable in transit or stronger in construction? As Judge Rich stated, the correct enquiry is whether or not this is a "'utilitarian design of a 'utilitarian' object.'"22

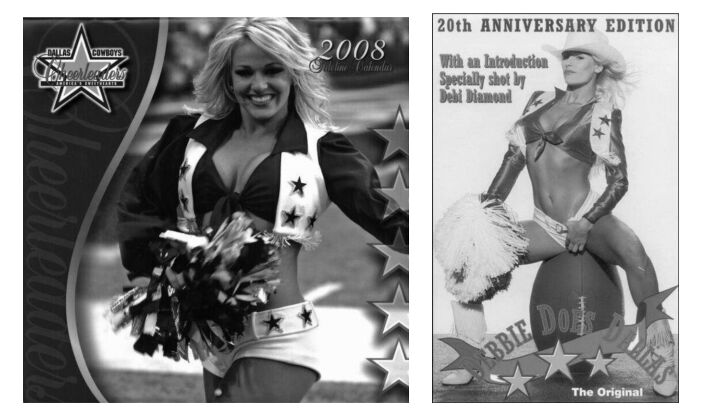

A famous example of the functionality defense at work concerned the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders' success in preliminarily enjoining an adult film company from distributing or exhibiting the infamous movie Debbie Does Dallas.23 At dispute was the functionality of the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleader uniform, composed of the "distinctive . . . white vinyl boots, white shorts, a white belt decorated with blue stars, a blue bolero blouse, and a white vest decorated with three blue stars on each side of the front and a white fringe around the bottom."24 One of the actresses in the motion picture donned a uniform "strikingly similar" to the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader's uniform. Shown below are modern specimens submitted to the USPTO depicting the trade dress at issue.

Focusing on the overall aspect of the uniform, the defendants "argue[d] that the uniform is a purely functional item necessary for the performance of cheerleading routines and that it therefore is not capable of becoming a trademark."25 The court rejected this argument and clarified that "[p]laintiff does not claim a trademark in all clothing designed and fitted to allow free movement while performing cheerleading routines, but claims a trademark in the particular combination of colors and collocation of decorations that distinguish plaintiff's uniform from those of other squads."26 In sum, "the fact that an item serves or performs a function does not mean that it may not at the same time be capable of indicating sponsorship or origin, particularly where the decorative aspects of the item are non-functional."27 Thus, "the combination of the white boots, white shorts, blue blouse, and white star-studded vest and belt is an arbitrary design which makes the otherwise functional uniform trademarkable."28

Functionality also arises where trade dress is claimed in a product that has functional aspects. An example of this is the Leatherman "Personal Survival Tool," or "PST" (shown below).29 Leatherman claimed trade dress protection in the PST and attempted to prevent a competitor from making a similar-looking device it called the "Toolzall."30 The district court found the trade dress valid and infringed, and entered a permanent injunction.31 On appeal, the Ninth Circuit reversed the finding of trade dress infringement.32

Before deciding the issue, the Ninth Circuit addressed the defense of functionality in some detail. Ultimately, the court found nothing about the appearance of the PST that was arguably non-functional:

There is no evidence, however, that anything about that appearance (other than the Leatherman name) exists for any non-functional purpose. Rather, every physical part of the Leatherman is de jure functional. No witness pointed to any feature of, or marking on, the PST (other than the Leatherman name) which was ornamental or intended to identify its source. . . .

Leatherman is correct that trade dress must be viewed as a whole, but where the whole is nothing other than the assemblage of functional parts, and where even the arrangement and combination of the parts is designed to result in superior performance, it is semantic trickery to say that there is still some sort of separate "overall appearance" which is non-functional.33

Though circuits may use different language regarding the test or definition of utilitarian functionality, most differences boil down to semantics.34 That is not to say that one should wholly ignore a particular circuit's parsing of its utilitarian functionality test, or that confusion about the application of such tests still persists. Indeed, one circuit firmly holds that the Inwood test applies to utilitarian functionality—leaving the Qualitex test for aesthetic functionality—while another circuit applies a two-tiered approach starting with the Inwood test and ending, if necessary, with Qualitex test.35

The Supreme Court has even waffled over the years in its approach to functionality. In 1983, the Supreme Court held (in Inwood) that "a product feature is functional if it is essential to the use or purpose of the article or if it affects the cost or quality of the article."36 Then, in 1992 (Two Pesos), the Supreme Court appeared to adopt a Fifth Circuit interpretation, holding that "a design is legally functional, and thus unprotectable, if it is one of a limited number of equally efficient options available to competitors and free competition would be unduly hindered by according the design trademark protection."37 A few years later (in Qualitex), the Supreme Court cited the Inwood test and supplemented it by adding that a feature is functional "if exclusive use of the feature would put competitors at a significant non-reputational-related disadvantage."38 Finally, in 2001 (TrafFix Devices) the Court clarified that the Qualitex 'competitive need' supplement to the Inwood test was not a "comprehensive definition."39 Rather, "[w]here the design is functional under the Inwood formulation there is no need to proceed further to consider if there is a competitive necessity for the feature."40

As discussed in Chapter 6, the circuit courts have not interpreted or applied TrafFix Devices uniformly, perhaps because it does not set forth a clear standard. For example, after TrafFix Devices, the Fifth Circuit adopted "primary" and "secondary" tests for functionality.41 The "primary test for determining whether a product feature is functional is whether the feature is essential to the use or purpose of the product or whether it affects the cost or quality of the product" (i.e., the Inwood test).42...

To continue reading

Request your trial