Chapter 10A Monroe Mountain - A Case Study in Effective Community Engagement in the NEPA Process

| Jurisdiction | United States |

JAKE GARFIELD is the Deputy Director of Utah's Public Lands Policy Coordinating Office, a state agency that acts as the Utah State Government's lead point of contact with the Federal land management agencies. Jake's practice focuses on intergovernmental relationships in public land management. Jake formerly represented the Utah Association of Counties as Natural Resources Counsel. He holds a B.S. in Economics from the University of Utah and a J.D. from Brigham Young University. In his free time, Jake enjoys hiking, skiing, and biking very slowly around Utah with his four kids in tow.

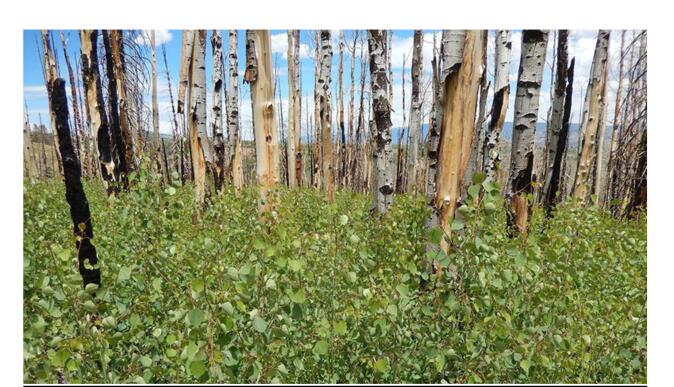

New aspen growth on a burned area of Monroe Mountain, Utah. (Photo Credit: Kreig Rasmussen)

Monroe Mountain-Background

Towering over the arid valleys of south-central Utah is Monroe Mountain, a high rolling plateau in Fishlake National Forest reaching over 11,000 feet.1 Monroe Mountain, covering an area of roughly 200,000 acres, was once home to one of Utah's largest aspen forests supporting tremendous biodiversity in its understory. These aspen groves provided homes to elk, deer, boreal toads, a vast array of birds and insects, and high value forage for domestic sheep and cattle.2 Nearby communities depended on the plentiful springs and streams originating in the high elevation meadows.

[10A-1]

Over a century of fire suppression and persistent drought has caused a severe decline in the mountain's aspen forests, which covered only a third of their historic range at the inception of the Monroe Mountain Aspen Regeneration Project.3 Conifer trees, once sparse on Monroe Mountain, pushed out aspen and deprived sun-loving saplings of needed sunlight.4 The forest floor, increasingly shaded by expanding conifers, lost much of its former plant life where native wildlife, birds and insects once thrived in the lush vegetation. Herds of domestic cattle and sheep increasingly struggled to find sufficient feed as spruce and fir species encroached into aspen groves. Many springs and streams declined as thirsty conifers siphoned off more of the water supply. The lack of wildfire prevented aspen clones from regenerating, with adult trees dominating in remaining aspen stands.

In short, the once-mighty aspen forests of Monroe Mountain were in steady decline, and needed the combined efforts of both the U.S. Forest Service and community stakeholders to turn the tide.

Golden Aspens on Fishlake National Forest (Photo Credit, Fishlake National Forest)

A Diverse Array of Community Stakeholders

[10A-2]

Officials at Fishlake National Forest knew that aspen on Monroe Mountain was in trouble, as did aspen scientists from around Utah who in 2010 put together Guidelines for Aspen Restoration on National Forests in Utah.5 In 2011, recognizing Monroe Mountain as the perfect test case to put the Guidelines into action, community stakeholders convened the Monroe Mountain Working Group ("the Working Group") to work with the U.S. Forest Service to find practical solutions for aspen decline on Monroe Mountain.

The Working Group brought together a diverse cross section of stakeholders on the mountain, including conservation advocates, livestock grazing permittees, hunting and fishing organizations, local forestry scientists, elected officials from county governments, and state agencies.6 These groups held widely different, and often competing, views on how Utah's public lands should be used and managed. Indeed, some of the stakeholders had previously been opponents on other land-management projects elsewhere in the state. But the problems on Monroe Mountain needed community collaboration and compromise, and all parties came to the table sincerely looking for ways to restore the mountain's ecosystem.

With Utah State University Sociology Professor Steve Daniels as the facilitator, stakeholders started meeting regularly to forge a path forward. The Working Group worked with Fishlake National Forest on a proposal to radically change the land management of Monroe Mountain, and thus the Monroe Mountain Aspen Ecosystems Regeneration Project was born. Soon, the Fishlake National Forest released its Notice of Intent to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement in October, 20127 .

Members of the Monroe Mountain Working Group8 :

-Utah Cattlemen's Association;

-Utah Woolgrowers Association;

-Utah State University Extension;

-Sportsmen for Fish and Wildlife;

-Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation;

-Trout Unlimited;

[10A-3]

-Utah Division of Wildlife Resources;

-Piute County;

-Sevier County;

-Utah Department of Agriculture and Food;

-Utah Farm Bureau;

-Rocky Mountain Research Station;

-Grand Canyon Trust;

-Western Aspen Alliance;

-Utah Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands;

-Monroe Mountain Grazing Permittees

Working Together Towards Consensus

Over the next three years, the Working Group continued their collaboration to help the U.S. Forest Service assemble its Environmental Impact Statement.9 The Working Group served as the primary conduit for different interest groups to share their concerns and ideas. Local communities communicated via elected county commissioners, hunters and fishers through the sportsmen's organizations, and grazing permittees through their dedicated representatives on the working group.10 Communication was candid and sincere, with all members of the working group listening to problems of individual members and finding ways to address them.11 The Working Group became the place for solving problems, rather than expecting Fishlake National Forest personnel to act as the mediator between various competing interests on Monroe Mountain.

The entire...

To continue reading

Request your trial