Chapter 1 Five Federal Lands Fundamentals: Brief Answers to Basic Questions on Federal Public Lands

| Jurisdiction | United States |

REED D. BENSON is Dickason Chair and Professor of Law at the University of New Mexico, where he teaches water law, natural resources, and administrative law and directs the law school's Natural Resources and Environmental Law Program. Benson has published over thirty-five articles on western water law and policy, and is a co-author of the Water Resource Management casebook from Foundation Press. He was a Fulbright Scholar in 2015, serving as Visiting Chair in Water and the Environment at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada. He served from 2002-08 on the University of Wyoming law faculty. He has been active with the nonprofit Foundation for Natural Resources and Energy Law (formerly the Rocky Mountain Mineral Law Foundation), and in 2021 he received the Foundation's Clyde O. Martz Award recognizing career achievement by a law professor. Before he began teaching, Benson worked in Oregon for the nonprofit conservation group WaterWatch, including five years as executive director. He has also worked as an attorney for a Boulder, Colorado law firm, for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in Washington, DC, and for a conservation group based in Colorado. He earned a B.S. with honors in economics and environmental studies from Iowa State, and a J.D. magna cum laude from Michigan.

[1-1]

Even the most basic and general overview of federal lands requires covering a lot of ground. This is true partly because there is so much federal ground, especially in the West. Nationally, the United States government owns about 640 million acres, about 28% of all land in the nation, but federal holdings account for a much greater percentage of Alaska (61%) and the 11 westernmost states of the Lower 48 (45%) than in the other 38 states (4.2%).1

Any overview must also account for the various types or designations of federal lands, each of which has its own management regime. Federal lands fall within at least five or six major categories, and four different agencies - each responsible for 80 million acres or more - manage the great majority of federal lands.2 This paper introduces both the major categories and the four primary agencies.

This paper offers the briefest possible introduction to federal lands history and law - two topics that can seem as extensive as federal lands themselves.3 It approaches these topics by posing six basic questions about the origins, governing law, categories, and management of federal lands, then answering each one in a few paragraphs.

1. How did the U.S. government come to own lands?

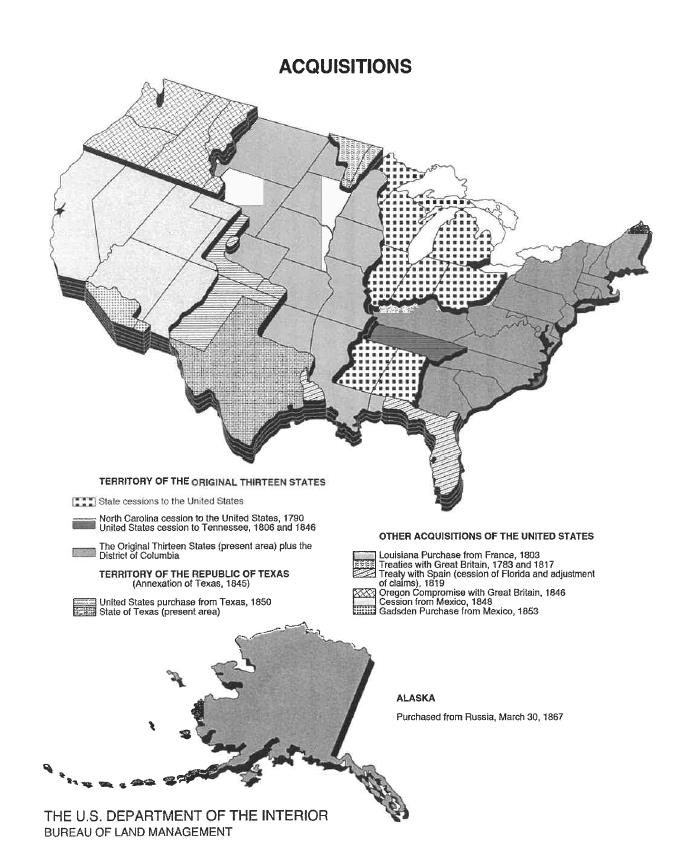

Today's federal lands were acquired by the government in various ways. Most of today's United States east of the Mississippi River is territory that was once part of the original 13 colonies. Seven of those colonies held extensive grants from the British Crown for lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, which those colonies/states eventually ceded to the government for the purpose of forming new states.4 Other lands within today's U.S. were acquired by some form of agreement with a foreign government: Spain (Florida and other Gulf Coast lands), France (Louisiana Purchase), Mexico (much of today's Southwest), the Republic of Texas (Texas and portions of other states), Britain (today's Pacific Northwest), and Russia (Alaska).5

[1-2]

[1-3]

At least some of the land that the U.S. Government acquired was regarded by some group of people - and may be regarded by their descendants today - as rightfully theirs. Indigenous peoples were dispossessed of vast and vital territories that they had long occupied, sometimes after the U.S. had made treaties or other agreements purporting to protect those lands.6 In other places, the U.S. regarded lands as "vacant" despite tribal occupation and use, and may have conveyed such lands to someone else.7 Thus, tribes and indigenous groups may dispute the legitimacy of federal ownership of some of today's public lands. Somewhat similarly, many modern descendants of Spanish or Mexican land grant holders believe that lands granted to their families or communities were taken from them unlawfully or unfairly; such lands may now be part of a national forest or other federal land area in the American Southwest.8

Other federal lands were purchased by the government, either under a general program or site-specific acquisition authority. For example, much of the national forest land in the eastern half of the United States was acquired via the Weeks Act of 1911, which authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to "purchase such forested, cut-over, or denuded lands within the watersheds of navigable streams as in his judgment may be necessary to the regulation of the flow of navigable streams or for the production of timber."9 Congress sometimes authorizes land acquisition in a specific area, as when it authorized the Interior Department to use Land and Water Conservation Fund money to buy the Baca Ranch, which would become the Valles Caldera National Preserve in New Mexico.10

2. Why does the government still hold so much land?

Much of the land that the U.S. government once owned is no longer in federal hands. From 1781 to the present, the government transferred over 1.3 billion acres to other entities, including 328 million to states (outside of Alaska), 287 million to homesteaders, 143 million to the State of Alaska, 94 million to railroads, and 61 million to military veterans.11 Thus, over the course of 240 years, the federal government conveyed over twice as much land as it now holds.

Some lands remain federal because the government reserved them for a specific purpose, such as a national forest or a military base. Congress made some reservations directly, as in establishing Yellowstone National Park;12 for many other types of federal land, it authorized the President to make reservations for identified purposes, as in the Antiquities Act.13 Other federal lands, although not reserved for a specific use, were withdrawn from one or more programs that otherwise would have much the lands available for use or acquisition, such as the Homestead laws. Such withdrawals were sometimes authorized by Congress,14 but sometimes the President simply ordered a withdrawal without having such clear statutory authority to do so. A divided Supreme Court upheld such non-statutory Presidential withdrawals in United States v. Midwest Oil Co.,15 in part because the power had been exercised

[1-4]

repeatedly over time without objection from Congress.16 Congress eventually provided a statutory framework for withdrawals under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLMPA) Section 204.17 FLPMA also established national policy that remaining federal lands should generally remain in federal ownership.18

opponents and critics of federal lands management have sometimes argued that much current government ownership is illegitimate. This argument is rooted in language from Pollard v. Hagen, an 1845 Supreme Court decision19 involving competing claims to waterfront lands in Mobile, Alabama. The Court's opinion seems to suggest that the federal government has very limited power to hold land within a state, because states upon admission to the Union should receive such lands under the Equal Footing Doctrine.20 But the holding in Pollard involved lands that had been submerged under Mobile Bay, so the Equal Footing Doctrine has resulted only in the beds and banks of navigable waters being transferred to newly admitted states.21 More recent cases have confirmed that the United States has power to retain lands within the states.22

3. What are the sources of law for federal land management?

The foundation of federal lands law is the Property Clause of the Constitution, which provides, "The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States ...."23 Thus, the Constitution gives Congress control over public lands, and the Supreme Court has interpreted this authority broadly. As the Court stated in Kleppe v. New Mexico, "[W]e have repeatedly observed that 'the power over the public lands thus entrusted to Congress is without limitations.'"24

Congress has exercised this authority by enacting a wide variety of statutes regarding federal lands. Some statutes apply generally to federal lands of more than one category, such as the Mineral Leasing Act25 or the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act.26 Others govern particular categories of lands, such as the Multiple-Use Sustained Yield Act27 for national forests or the Wilderness Act28 for wilderness areas. But many federal lands statutes - probably most - apply only to a particular unit or area, such as the Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area29 (oregon) or the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area30 (Arizona).

[1-5]

Executive actions, mostly site-specific ones, provide another important source of federal lands law. Probably the best-known executive actions are Presidential proclamations under the Antiquities Act31 creating national monuments, such as President Clinton's action to establish the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (Utah).32 Other actions are taken by agencies pursuant to statute, such as land withdrawals authorized by FLMPA Section 204;33 for example, the Interior Department in 2013 withdrew over 300,000 acres of land in six states for Solar Energy Zones.34

Agency rules are another important source of federal lands law, as management agencies exercise rulemaking authority delegated by Congress. The Supreme Court upheld this arrangement over a century ago, holding that Congress could lawfully empower the Forest Service to "fill up the details" by adopting rules governing use of federal lands.35 Today, rules adopted by the management agencies make up a...

To continue reading

Request your trial