The First Amendment Follies: Forbidden Films and the Kansas State Board of Review

| Publication year | 2019 |

| Pages | 21 |

| Citation | Vol. 88 No. 10 Pg. 21 |

by Mary Feighny

The Taming of the Snood

Date of Review: 1940-06-11

Company Name: Columbia Pictures Corp.

Starring: Buster Keaton

Contains Smoking: [Not Stated]

Eliminations: Reel 1B: Cut close-up scene where maid is shown astride Buster's neck. Reel 1B: Eliminate scene where maid is shown in bending position and Buster places hand upon her body.

Imagine watching When Harry Met Sally, a 1989 film starring Meg Ryan and Billy Crystal playing two college acquaintances whose relationship evolves over the years and, eventually blossoms into romance. The couple are dining in Katz's Deli in New York. Meg, trying to explain to a boastful Billy that women do, on occasion, fake orgasms, begins to writhe, invoke the Lord's name, and moan with abandon, prompting a middle-aged woman at the next table to exclaim: "I'll have what she's having."

Had this movie been distributed in Kansas prior to 1968, the deli scene would have been cut by the Kansas State Board of Review, an agency whose charge was to ensure that only clean and wholesome films, as determined by "three well-educated Christian women," reached Kansas movie theatres. This article chronicles the agency's rise and demise, felled eventually, by the First Amendment.

I. That's Entertainment

In 1894, the first public protest of a motion picture erupted in New York City: Dolorita in the Passion Dance—shown on a Thomas Edison kinetoscope.[1] Fearful of a raft of Doloritas invading the state and leading Kansans down a dark path, the Kansas legislature established, in 1913, the State Censor Board, whose mission was to review all "moving—picture" films before they could be exhibited in the state.[2] Exhibiting an unapproved film exposed the theatre owner to criminal prosecution, with a maximum fine of $100 per day.[3]

The state superintendent of public instruction was tasked with rejecting moving picture films that were "'sacrilegious, obscene, indecent, or immoral, or such as tend to corrupt morals.'[4] An unhappy theatre owner could appeal the decision to a committee comprised of the governor, the attorney general, and the secretary of state, whose decision was final.[5]

Not surprisingly, this law—like similar laws throughout the nation—was challenged as offensive to the First Amendment. However, the U.S. Supreme Court rebuffed the fledgling motion picture industry by upholding an Ohio law that authorized its censors to reject all films unless "of a moral, educational, or amusing and harmless character."

It cannot be put out of view that the exhibition of moving pictures is a business, pure and simple, originated and conducted for profit, like other spectacles, not to be regarded . . . as part of the press of the country or as organs of public opinion. They are mere representations of events, of ideas and sentiments published and known; vivid, useful, and entertaining, no doubt, but, as we have said, capable of evil, having power for it, the greater because of their attractiveness and manner of exhibition. It was this capability and power, and it may be in experience of them, that induced the state of Ohio, in addition to prescribing penalties for immoral exhibitions . . . to require censorship before exhibition, as it does by the act under review. We cannot regard this as beyond the power of government.[6]

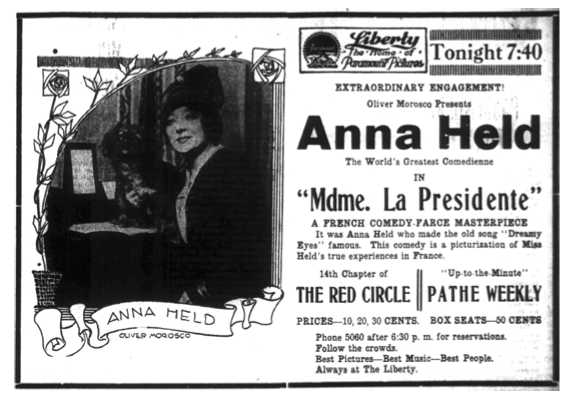

The State Censor Board was overhauled in 1917, perhaps in part, because Governor Arthur Capper felt that he had more important things to attend than watching Madame La President.[7] Madame was a silly farce about a young actress working her feminine wiles on the stuffy and married judge responsible for evicting her from a hotel. The Reverend Festus Foster convinced the state superintendent to reject the film because it would "shake the confidence that women have in their husbands." [8]

That seems to be its lesson, that you can't trust a man ... Now, men are to be trusted. At least 50 percent of the men in Kansas are as virtuous as the purest woman. Not one man out of 10 would flirt with a married woman. They are above such things. I have great confidence in the morality of the Kansas man, and any picture that represents men in general as weak and of loose character is harmful. [Miss Anna Held] displays too much of her personal charms. She does it with the purpose of stirring masculine passions. That condemns the picture. [It] is the purpose of the Kansas censor to put the ban on anything that is harmful. It is better that our people know nothing of the wicked ways of the world.[9]

The appeal committee, possibly concurring with Miss Held's opinion that the minister was an "old fogey,"[10] reversed the decision. Unhappy in his role as movie critic in-chief, Governor Capper expressed his displeasure:

The most ridiculous laws a legislature ever enacted is that which makes the Governor, Attorney General and Secretary of State an appeal board. If these three officers should attempt to carry out the spirit of the law it would take most of their time to look at pictures. I do not believe the constitution of the state of Kansas contemplated anything of the sort. I have been obligated to ignore this law simply because it was a physical impossibility to comply with it. I shall insist that the next legislature repeal that provision of the censorship law.[11]

Heeding Governor Capper's request, the legislature, in 1917, created the Kansas State Board of Review comprised of three gubernatorial appointees "qualified by education and experience to act as censors."[12] The salaries were insufficient to attract male candidates so, with one exception in the Board's 50 year history, the members were female.[13]

This gender disparity sometimes created problems when the members wielded their scissors to excise portions of films that, in the view of at least two members, "'tended to debase or corrupt morals.'

In 1920, WH. Huston, owner of the Columbus Advocate, thought that the board would benefit from a masculine presence and, as such, requested Governor Allen to "get rid of some of the petticoats" as "one would be a-plenty."[14]

Our present board carries the Puritan view to an extreme. They see indecency where none exists. They insist upon the wronged girls being all "'secretly married' in the first reel — even though it upsets the continuity of all the rest of the story. In Heart of Humanity, they cut out the wonderful scene where the dog rescues the nurse in No Man's land, when a wounded Hun tried to grab her. I saw this picture in Joplin, Missouri and when the dog leaped at the man's throat, and apparently tore him to pieces, the audience stood up on chairs and cheered! Our dear lady censors (God bless them) said this scene was "'too shocking' so out it went. There are dozens of cuts this board made in war pictures, so much so that it was a common remark among picture men that the board was pro-German.[15]

The first members of the Board of Review were Mrs. J.M. Miller, Chair; Miss Carrie Simpson, and Mrs. B.L. Short—'well-educated Christian women of average intelligence.'[16] In the Board's annual review covering the period of 1917-1918, Mrs. Miller noted that the mem-bers endeavored to "give to the state a class of films free from immoralities and possessing artistic and educational value... insisting on clean, wholesome films... and [eliminating] those things which tend to debase morals or establish false standards of conduct.'[17] They were particularly concerned with films depicting crimes, sex relations, and "comedy of the slapstick variety— much of which was of such disgusting character...and evil suggestiveness" that the Board "protested long and loud against [its] production."[18]

Rather than rejecting a movie in toto, the Board, noting that "'every film possesses some merit,' preferred to order excisions from the reels to eliminate offending portions. Sometimes the excisions were made; sometimes not—most likely because the Attorney General urged the Board to pursue a policy of enforcement without criminal prosecution.[19] Undeterred, the Board's regulations enunciated its review standards:

1. Ridicule of any religious sect or peculiar characteristics of any race of people will not be approved.

2. Evil suggestion in the dress of comedy characters will be eliminated.

3. Infidelity to marriage ties will be eliminated.

4. Loose conduct between men and women, cigarette smoking by women will be eliminated, and, whenever possible, barroom scenes and social drinking.

5. A display of nude human figures will be eliminated.

6. Crimes and criminal methods such as give instruction in crime through suggestion will be eliminated or abbreviated.

7. Prolonged and passionate love scenes, when suggestive of immorality, will be eliminated.

8. Scenes of houses of ill fame, road houses and immoral dance halls will be eliminated.

9. The theme of white slavery or allurement and betrayal of innocence will be condemned.[20]

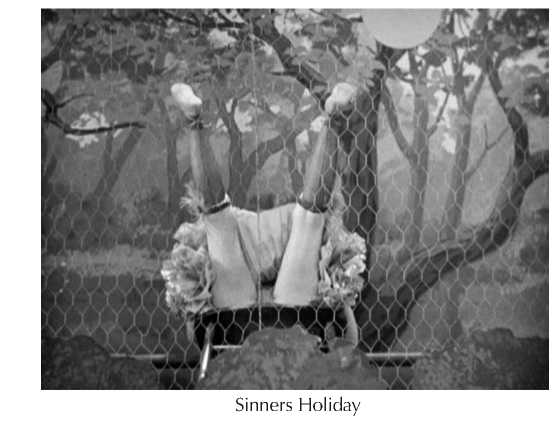

In Sinners Holiday, scenes of "'girls on a rack swinging backward showing legs and posterior' were ordered excised.[21] The producers of Compromise had to eliminate a scene with "'girls sitting on man's lap' and a close-up of a "'girl in wiggly dance.'[22]In the silent film Oh, What a Nurse, the title "'Little Totsie...

To continue reading

Request your trial