Land Description Errors: Recognition, Avoidance, and Consequences

| Publication year | 2009 |

| Pages | 20 |

By John C. Peck and Christopher L. Steadham

I. Introduction

The legal description of a parcel of land is an important element in a real estate transaction. The land sales contract, mortgage, and deed are the three obvious places a description appears. Descriptions also appear in correspondence, real estate brokerage listing contracts, leases, options, puts, rights of first refusal, auction advertisements, subordination agreements, oil and gas leases, water rights documents, appraisals, lawsuit pleadings and judgments, divorce settlement agreements, mechanic's lien notices, and legal notices in newspapers. Transactions involving personal property must also contain accurate descriptions of the property, but one element involved in real estate that distinguishes it from personal property is the fact that real estate does not move,[2] and each land parcel sits next to neighboring parcels. A mistake in the description of one parcel might leave a strip between the two parcels or might create an encroachment.

Legal description errors are common[3] and can cause serious problems for buyers, sellers, mortgagors and mortgagees, optionors and optionees, condemnors and condemnees, title insurance companies, abstractors, and others. Ultimately it can become a problem as well for the lawyer who makes a mistake in a land description. Even judges make errors writing opinions about errors in legal descriptions. In Cities Service Oil Co. v. Dunlap et al.,[4] a federal case from Texas that went to the U.S. Supreme Court and involved an apparently valuable strip of land, the federal appeals court from Texas made at least five errors in the opinion itself – e.g., misstating chains for yards, making errors in distance measurements, and misstating lot numbers.

Land lawyers must understand legal descriptions in order to read, check, and draw legal descriptions in legal documents. Lawyers in other areas of practice need to know when to call in a land lawyer or surveyor with expertise in reading and drawing legal descriptions. We say lawyers need to know how to "read, check, and draw" legal descriptions, not to "write" or "draft" them. Kansas statutes on rules governing the establishing and practicing of the technical professions, including land surveying, appear to limit the drafting of "original descriptions of real property for conveyance or recording" to licensed land surveyors.[5] Although these statutes are not entirely clear on this limitation,[6] the question of the lawyer's versus the land surveyor's rights in the arena of drafting land descriptions is not the focus of this article, but could be in another article.

The purpose of this article is to provide some information to help avoid these errors. We first give a brief overview and review of the standard methods of describing land. The article then presents information about how and where land description errors occur. To demonstrate the consequences of making these errors, we summarize several cases on errors in land descriptions and include issues raised in the area of a lawyer's professional responsibility. Lastly, we make several simple and modest suggestions for ways to avoid the errors and their consequences. This article is not meant to be a treatise on surveying or land description methods. Perusing some classic texts[7] reveals how complicated these surveys can be. We hope this article will serve as a beginning point for a new land lawyer and a review for an experienced lawyer.

II. Land Description Methods[8]

We briefly present four land description methods[9] used by surveyors and lawyers — metes and bounds, the U.S. Government Survey System (sometimes referred to as the Rectangular Survey System), the angular or surveyor's method, and the plat reference — but leave it up to the reader who needs more information to obtain it elsewhere. Depending on geographical location within the United States, a combination of these methods may occur in one land description. For example, a description of a parcel of land in Kansas or Nebraska could employ metes and bounds, U.S. Government Survey, and the angular methods.

A. Metes and Bounds[10]

This method, used often in the states of the original colonies, is much like the way a person would informally direct another person to trace the boundaries around a parcel of land. The person would be told where to start at a point and then where to go, point by point, with a series of "calls" or operating commands to trace the entire parcel. From a point of beginning, the person goes from various "monuments" (either natural monuments like trees, or artificial monuments like iron rods) around the perimeter and back to the beginning point. A call typically contains distances and directions. Sometimes a call contains an "adjoiner," which is a boundary of an adjacent land owner or of a river or road. Typically, the description contains a general location in the region (e.g., "approximately two miles west of Batesville, Va.") and ends with an approximate area notation, in acres or square feet.

The area described should "close," i.e., all of the calls should take one from the point of beginning around the tract and end at the point of beginning, with no missing lines. If it does not close there is a problem, unless the description is meant to be two-dimensional, like a line (e.g., the centerline of a pipeline easement).

B. U.S. Government Survey

Much of the United States lying west of the original 13 colonies, except Texas, is covered by the U.S. Government Survey. To understand this system, one must have an understanding of "meridians" and "base lines," as these are the framework upon which the system is built. A "meridian" normally refers to a north-south line passing through the North and South Geographic Poles. A "base line" is a line that runs straight east and west. Throughout the country, there are principal meridians and base lines that intersect them (depending on one's reference material, there are from 35 to 37 principal meridians in the United States).

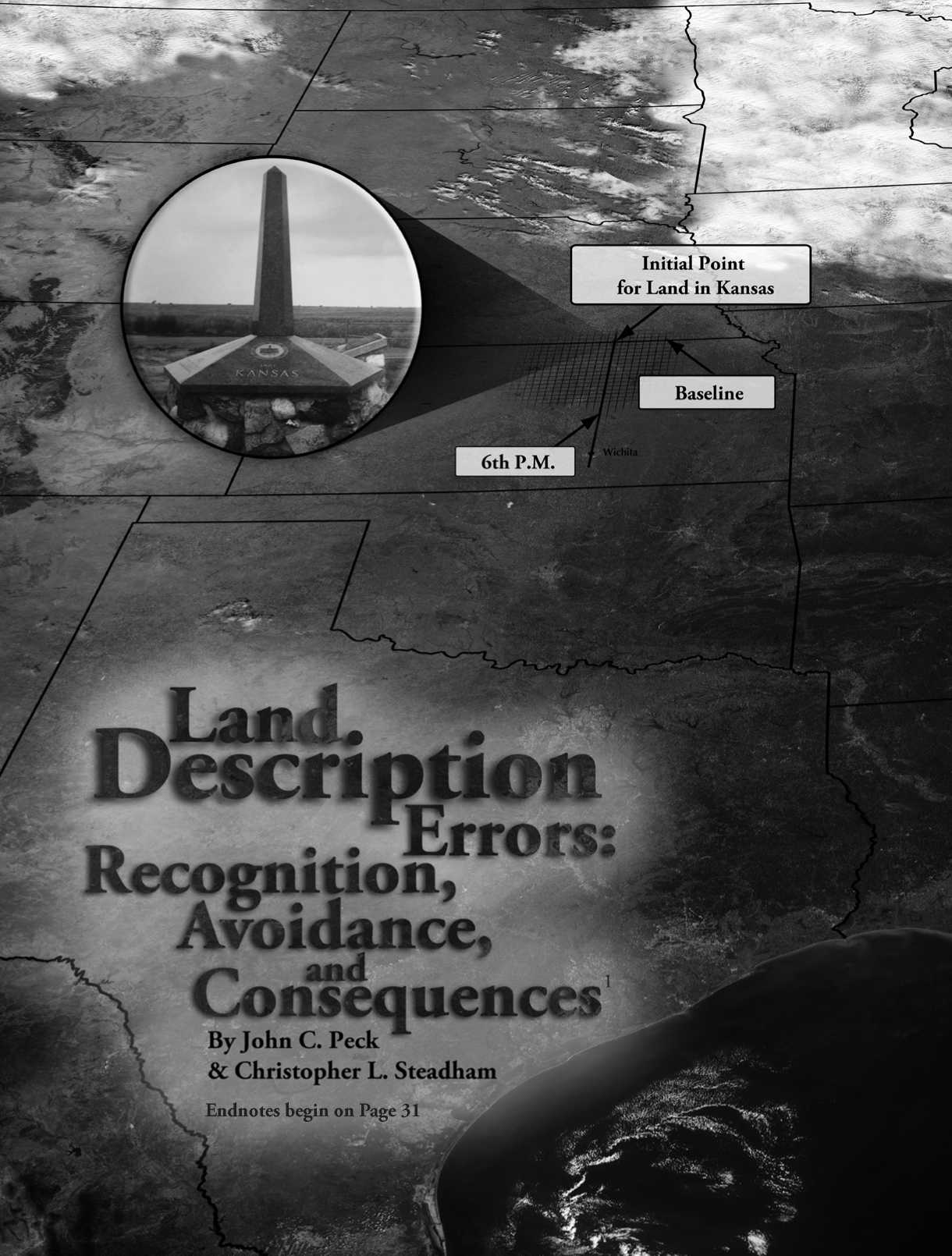

The Kansas reference point is located near Belleville at the intersection of the "6th Principal Meridian" (6th P.M.) and its base line, the Kansas-Nebraska border. The point at this intersection, the so-called "initial point," controls legal descriptions in Kansas and Nebraska, as well as parts of Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota. See the cover page.

For each principal meridian and base line in the country, township lines are run east and west and six miles apart, both north and south of the base line, forming 6-mile-wide strips of land running east and west throughout the area being surveyed, referred to as "townships." Range lines are run north and south and six miles apart, both east and west of the principal meridian, forming 6-mile-wide strips of land running north and south throughout the area being surveyed, referred to as "ranges." The resulting 6-by-6-mile squares are sometimes referred to as "townships" or "congressional townships." Because all land in Kansas is south of the base line (i.e., the Kansas-Nebraska border), the first township south of the base line is designated as Township 1 South, the next township as Township 2 South, etc. There are 35 townships in Kansas extending to the Oklahoma border. Likewise, ranges are numbered east and west of the 6th P.M. (i.e., Range 1 East, or Range 2 East, etc., or Range 1 West, or Range 2 West, etc.). There are 25 ranges east and between 41 and 43 ranges west of the 6th P.M. in Kansas, depending on location.

Each 6-mile square township in Kansas has both a "township" designation running south of the 6th P.M., and a "range" designation running either east or west of the 6th P.M. Townships to the south and east of the 6th P.M., for example, are numbered as Township 1 South, Range 1 East; Township 2 South, Range 2 East, etc. Townships to the south and west are numbered as Township 1 South, Range 1 West; Township 2 South, Range 2 West, etc. Figure 1 shows a close-up of the 6th P.M. and township numbering in townships in the vicinity of the 6th P.M.

Fig. 1 Townships in the Vicinity of the 6th P.M.

The location of the 6th P.M. was not chosen as a logical point, like "the intersection of the 100th Meridian and the Kansas-Nebraska Border." According to an article in the January 1937 Kansas Abstracter magazine,[11] the surveying team was instructed to take their horses, wagons, and surveying instruments and proceed west from the Missouri River along the Kansas-Nebraska border, to construct earthen mounds every few miles, to go west until they "struck the desert," and then to go "one full day's march into the desert and establish the Sixth Principal Meridian."[12] Which they did. Based on these instructions, today one would imagine that the 6th P.M. should be located in, say, Utah, but, instead, it runs north and south through Kansas and is generally located straight north of Wichita (it runs along Meridian Street in Wichita to approximately one mile west of Solomon, Kan.) and today can definitely be pinpointed as having a longitude of 97 degrees, 27 minutes west of the Greenwich Meridian.

Old maps show the "Great American Desert" to start at about the 100th Meridian.[13] A marble obelisk monument to the establishment of the 6th P.M. was erected near the site and dedicated on June 11, 1987. See the cover page.

Townships contain roughly 36 square miles. They are six miles on a side, divided into 36 "sections," which measure one mile by one mile. Political townships are different, but often have boundaries that coincide with the surveyed township. Sections are numbered internally starting in the northeastern-most section, running west 1 through 6, then down and back east 7 through 12, and then down and west again, etc...

To continue reading

Request your trial